This January marks the 200th anniversary of the birth of the College’s most famous alumnus. Were you thinking John C. Frémont? If not, perhaps it’s time to go back to class.

by Mark Berry

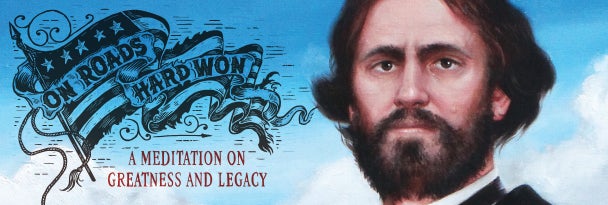

Painting and Illustrations by ’Max Miller

Students, please take your seats now. We have a lot to get through and not much time. Today is going to be a little different. Please put away your notebooks, your papers, your pens, your laptops, even your smart phones, and settle in. In keeping with the spirit of the subject, this lesson must simply be heard – and remembered. Or not remembered, as the case may be.

Today’s subject is one that should be familiar to you. But in all likelihood, this historic figure is simply a boldface name, among many, memorized in your middle school or high school history class and soon forgotten after that quiz covering early American exploration.

That’s OK. But now that you’re here at the College, that boldface name should mean a little more to you. In your wanderings around campus, have you come across a portrait, a statue, a dusty nameplate tucked away down some hall in one of our many historic buildings? Yes? Good. Have you found one that celebrates perhaps one of the most famous figures of the 19th century and one that claims the College as his alma mater? No? Interesting.

Well, his story is complicated, to say the least. It’s one of great adventure, of incredible financial success and of stunning financial failures. His life is a rollercoaster ride of international fame and public adoration, intense rivalry and political backstabbing, progressive policy making and ineffectiveness in the field of battle.

Whose story, you ask? Oh, yes. His name is John Charles Frémont, and he’s a person that everyone here should know.

One thing you may not understand about history is that we tend to simplify it. Real people become caricatures, like the kind you see drawn at state fairs and amusement parks. Certain attributes are exaggerated for effect, but, over time, those exaggerations come to dominate the entire portrait. It’s only natural. It’s easier to lump people into categories and move on. Imagine a person 200 years from now trying to understand you. They will pick out one or two details of your life – the ones they find important – and that will be your legacy.

But Frémont is a different character. If you were a state-fair artist, you would have a tough time with him because, what do you focus on? What environment do you put him in? What context do you give him? What outfit is he wearing – a buckskin jacket, a politician’s suit, a general’s uniform? And what do you celebrate? What do you abhor? Maybe because he defies easy description, Frémont has slipped from our national consciousness.

Let’s remedy that, if we can. It’s time to take that fuzzy caricature and add shading, depth and color to the portrait. Let’s put flesh where cartoon skin resides.

Now, in order to do that, we need to make Frémont a little more real to us. Imagine Charleston in the late 1820s and early 1830s. It’s a port city run by plantation elite. In the mix is a smart kid, but with a checkered background (his mother, the wife of a Virginia planter, had run off with her French tutor – Frémont’s father, who then died when his son was very young). So, we have a boy of illegitimate birth who grows up without a dad and in a town not connected with his extended family. In those days, your family situation determined your social status. Being a bastard child did not portend greatness.

When Frémont turned 14, his mother, like many parents of limited means, sent her oldest son into the workforce in order to help with the family expenses. He worked for a local attorney, John W. Mitchell, who saw in Frémont a very bright mind. Mitchell actually paid for Frémont to study part time under John Roberton, who ran a private school that prepared boys to enter the College.

Years later, Roberton recalled Frémont as “graceful in manners, rather slender, but well formed, and upon the whole, what I would call handsome; of a keen, piercing eye, and a noble forehead seemingly the very seat of genius.”

His teacher also marveled at Frémont’s voracious appetite for learning. Within a year of study, Frémont had read Caesar, Nepos, Sallust, Virgil, Horace, Livy and Homer, among many other classics – the staples of an early-19th-century liberal arts education.

When Frémont was 16, he entered the College’s junior class. Think about that for a second – a transfer student (before transfer students), a boy of lower status, coming into a world where the wealthy of Charleston learned. Whatever social tensions may or may not have existed between Frémont and his classmates, he seemed to excel.

Let’s hear directly from Frémont about his college experience:

I was fond of study, and in what I had been deficient easily caught up with the class. In the new studies I did not forget the old, but at times I neglected both. While present at class I worked hard, but frequently absented myself for days together. This infraction of college discipline brought me frequent reprimands. During a long time the faculty forbore with me because I was always well prepared at recitation, but at length, after a formal warning neglected, their patience gave way and I was expelled from college for continued disregard of discipline. I was then in the senior class. In this act there was no ill-feeling on either side. My fault was such a neglect of the ordinary college usages and rules as the faculty could not overlook and I knew that I was a transgressor.

You see, Frémont had fallen in love with a girl named Cecilia and skipped class – a lot. He was expelled by the faculty in 1831, just three months shy of graduation.

Was Frémont regretful? Not really. Later in life, he reflected on his immediate post-expulsion existence: “Those were the splendid outside days; days of unreflecting life when I lived in the glow of passion …”

Like most teenage affairs of the heart, that love didn’t last. But, fortunately, another connection he made during his college days did: Frémont had made a good impression with a member of the College’s Board of Trustees. When Frémont met him, Joel Poinsett was a world traveler who had just finished his duty as the first U.S. minister to Mexico. Most of us know Poinsett today not because of his remarkable and varied public service, but because of his passion for botany. While in Mexico, he had sent home samples of a crimson, winter-blooming plant, later to be called

the poinsettia.

Like the attorney Mitchell, Poinsett recognized in Frémont a rare intellect. And, in turn, Frémont was inspired by Poinsett’s travels and worldly knowledge. Poinsett secured a teaching position for Frémont aboard the USS Natchez, which was traveling out of Charleston to South America. When Frémont returned from that two-year excursion, he applied for a professorship of mathematics with the U.S. Navy. He aced the exam and was offered the position – which he declined.

Life aboard a ship had not inspired him, and Frémont looked intensely for adventure, which in young America was as simple as pointing west.

In the meantime, the College’s faculty had seen Frémont mature and recognized his promise as a man of intellectual ability. They conferred upon him both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in 1836. “The college authorities had wrapped themselves in their dignity,” Frémont remembers, “and reluctantly but sternly inflicted on me condign punishment. To me this came like summer wind, that breathed over something sweeter than the ‘bank whereon the wild thyme blows.’”

For those of you who haven’t had your English 101 course yet, Frémont is showing off here by quoting one of the more famous passages from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. We’ll discuss that swagger a little bit more later.

So, Frémont had his degree, but no job – just a lot of enthusiasm and a restless spirit. Again, CofC trustee Poinsett came to Frémont’s aid. He helped him land a position as an assistant engineer on a survey of a projected railroad route from Charleston to Cincinnati. Frémont next joined a team surveying the Cherokee lands of western North Carolina, northern Georgia and eastern Tennessee (the government was preparing for the tribe’s removal and the influx of white settlers). In the wilderness, Frémont found his purpose and a freedom of spirit.

“Shut in to narrow limits,” Frémont writes in his memoirs, “the mind is driven in upon itself and loses its elasticity; but the breast expands when, upon some hill-top, the eye ranges over a broad expanse of country, or in face of the ocean. We do not value enough the effect of space for the eye; it reacts on the mind, which unconsciously expands to larger limits and freer range of thought.”

When Poinsett was appointed secretary of defense under President Martin Van Buren, he formed the U.S. Corps of Topographical Engineers in order to better understand the lands west of the Mississippi River. Poinsett paired Frémont with the corps’ head, Joseph Nicholas Nicollet, a gifted French geographer who would train Frémont to approach exploration with a scientist’s keen eye for observation and accuracy.

When Poinsett was appointed secretary of defense under President Martin Van Buren, he formed the U.S. Corps of Topographical Engineers in order to better understand the lands west of the Mississippi River. Poinsett paired Frémont with the corps’ head, Joseph Nicholas Nicollet, a gifted French geographer who would train Frémont to approach exploration with a scientist’s keen eye for observation and accuracy.

The next decade, from 1838 to about 1846, was really Frémont’s heyday as an explorer. During that time, he traveled thousands upon thousands of miles, endured some of the harshest conditions, from extreme heat to blizzard snows, and investigated lands that even the native tribes would not cross or inhabit. To call Frémont an extraordinary explorer would be an understatement. In those days, he was the explorer, eclipsing even Lewis and Clark in stature and impact.

And he was a national celebrity. Every aspect of his life seemed enchanted. Frémont was Hollywood before there was a Hollywood. Even in his love life, he commanded headlines. In 1841, as his star continued to rise, he eloped with Jessie Benton, a rare beauty by all historical accounts, and the daughter of Thomas Hart Benton, one of the most powerful politicians in the nation (and, as a U.S. senator from Missouri, a major proponent for Western expansion).

Regarding his explorations, newspaper editors and columnists drew comparisons of Frémont to a popular fictional character – James Fenimore Cooper’s Natty Bumppo from The Pathfinder (1840). Frémont, you might say, was one of America’s first real-life action heroes.

But that moniker, Pathfinder, is a little inaccurate. Frémont wasn’t interested in necessarily uncovering new territory and blazing new paths. His primary aim was to map and survey routes that were already, in effect, being used by a handful of intrepid pioneers heading west.

When your history teachers talk about Manifest Destiny, they probably quote Horace Greeley’s famous admonition to “Go West, young man.” In the 1840s and 1850s, knowledge of the West was limited, very limited. And here, Frémont’s published scientific maps and writings proved invaluable for those planning to cross the continent, and they inspired many Americans to conceive of a two-ocean nation. The poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote, “Frémont has particularly touched my imagination. What a wild life, and what a fresh kind of existence! But, ah, the discomforts!”

Through his reports, readers experienced the thrill of Western exploration firsthand. They felt the tension of traveling in places where, in a blaze of whoops and hoofbeats, warring tribes might appear out of nowhere and descend on your party. They knew the excitement of climbing the tallest peak in Wyoming’s Wind River Ridge and shooting the rapids on a rubber raft (one of the first of its kind) on the Platte River. And they now understood the rush of chasing alongside a herd of buffalo, attempting to dodge gopher holes and trying to raise and aim a rifle one handed on the back of a galloping horse.

Frémont’s writings were not just a great adventure tale, they also gave detailed notes of where to water horses, where grass was abundant and, more important, where it was sparse (grass was gas, you might say, for a pioneer). Frémont included information about suppliers, native tribes, flora and fauna – a road map and survival guide wrapped into one.

What was once a trickle of those moving west became a steady stream – or a flood tide, to be more precise. Frémont, perhaps more than any figure in the 19th century, turned the idea of Manifest Destiny into a reality and changed the face of the West.

It would be easy to close the book now on Frémont and simply remember him as the explorer, the incredible man of endurance who mapped the Oregon Trail, named Nevada’s Great Basin and Humboldt River and coined the term Golden Gate in San Francisco Bay. But his story doesn’t end there.

What Frémont called his “unrestrained life in the open air” was only a part of his career. And although his days of exploration would ultimately prove to be his most significant triumphs, he did not stop grasping for greatness. Perhaps when you’ve survived starvation, Indian raids, whitewater tumbles, grizzly bears and the death of trail mates in the remotest wilderness, your sense of limits is a little different than the average person’s.

And, here, the legend of John C. Frémont, as we’ve looked at him, changes. The noble portrait muddies somewhat with the complexities of his time

and culture.

Let’s ask Christophe Boucher, one of the College’s history professors and an expert on Western history, what he thinks.

“Frémont could be considered a postmodern hero before his time. If he had to wear a cowboy hat, his would be gray (possibly in a darker shade). Just like a character in a Clint Eastwood Western movie, Frémont is both a villain and a hero. It depends on one’s perspective,” says Boucher. “For John O’Sullivan [political writer and newspaper columnist] and those who endorsed Manifest Destiny, Frémont stands out as a hero who contributed to U.S. expansion out west. I’m not sure that the Native Americans or the Hispanics who got dispossessed as a result of this ideology were necessarily as enthusiastic. He was definitely influential, but his role in Western history should not eclipse that of other individuals who belonged to groups (Hispanics, Native Americans, Chinese, African Americans, etc.) who have long been silenced in the history of the region.

“Frémont’s impulsiveness, rash judgment and insubordination tend to undermine his image as a hero,” Boucher adds. “These are not actions that can be easily swept under the carpet or that we can consider household values. At times, the American public can suffer from very bad cases of amnesia and display a very selective historical memory. I prefer to think of him as a representative figure in the history of the American West.”

The “household values” Boucher alludes to pertain to Frémont’s actions in the Mexican War, when he helped lead American forces against the Hispanic population in California. Bear in mind, Frémont had not been sent to California on a military expedition; he was supposed to be surveying the eastern portion of the Rocky Mountains, but for unexplained reasons, he took his men farther west. Stated or unstated, Frémont knew there was an opportunity for the U.S. to push the region into open rebellion against the Mexican government.

The fog of war, however, would eventually play against Frémont. In California, there was no clear U.S. presence, no clear strategy for fighting. Two military heads jostled for power – a U.S. Naval officer and a U.S. Army officer. Upon Frémont’s victory over Californio military commander Andres Pico (leader of the Mexican forces) and his negotiation of peace terms in the Treaty of Cahuenga, both U.S. military officers tapped Frémont to become the territorial governor; however, when the Army officer (Frémont’s actual superior since the Topographical Corps reported to the U.S. Army) ordered him to relinquish power just a couple of months later, he initially refused. Frémont thought the Naval officer was the ranking official. Even though Frémont did give up the governor’s role, he was later court-martialed and found guilty of mutiny, disobedience of a superior officer and military misconduct.

His trial, as to be expected for a “hero” of the West, became a national sensation. Although President James K. Polk commuted his sentence and reinstated him, Frémont still resigned from the U.S. Army. His honor and name, in Frémont’s mind, had been irrevocably tarnished.

Now, we start seeing Frémont in a new light: brash, rash, yet still full of dash. While most newspapers saw this trial as the old-boy network versus a charismatic upstart (remember, America has always loved the underdog), others began detecting a whining tone in Frémont’s protests, and they sensed a growing ego unable to handle the slightest bit of criticism.

By the mid-1850s, Frémont’s fortunes had changed. Or, we should say, fortune. He was very rich now. After resigning from the U.S. Army in 1848, Frémont took his family to central California, where he had purchased 46,000 acres of land in Las Mariposas for about $3,000. We might even call Frémont one of the first forty-niners because gold was discovered on his property, and he became very rich (we’re talking multimillionaire). However, because his property had no set boundaries and no clear title, claim jumpers were a constant headache over the years. The manifold legal troubles dealing with them and the 29 ore-bearing veins on his property eventually proved too costly, so he sold his interests in the land to New York speculators in 1862.

But that’s a few years in his future.

The year 1856 was a pivotal one for Frémont. With the country splitting over slavery and its expansion west, regional tensions mounted with each presidential election. The Democratic Party, which did not want to re-elect Franklin Pierce, approached Frémont (a Southerner with ties across the country) to be their candidate. However, the Democrats, in Frémont’s estimation, were the party of slavery, so he declined.

Portrait of Frémont as a national political figure in 1859 by steel-plate engraver and lithographer john Chester Buttre

The newly formed Republican Party then asked Frémont to be their candidate. Imagine that today: two political parties trying to lure the same guy to lead their ticket.

Frémont agreed with the Republican stance against slavery, the Kansas-Nebraska Bill and the Fugitive Slave Law as well as the party’s opposition to repealing the Missouri Compromise. Soon, Republicans across the country were calling for “Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Speech, Free Men and Frémont.”

That election year, several biographies came out celebrating the explorations of the “Great Pathfinder” (even then, people knew the value of good marketing) and extolling Frémont as the very spirit of America. Walt Whitman dedicated his 1856 version of Leaves of Grass to his presidential candidacy, and John Greenleaf Whittier wrote the poem, “The Pass of the Sierra,” ending with this call to action: “Rise up, Frémont! and go before; / The Hour must have its Man; / Put on the hunting-shirt once more, / And lead in Freedom’s van!”

Unfortunately, it was an ugly campaign, and a lot of Frémont’s past, both real and fabricated, circulated in the newspapers: his illegitimate birth, rumors of his being Catholic (he was Episcopalian) and a slaveholder (he wasn’t), criticisms of his handling of an expedition in the San Juan Mountains (in which 10 of his men died or one-third of his party) and claims of excessive brutality in his military conquest of California. Despite all of that, Frémont narrowly lost to James Buchanan in a three-way race (Buchanan won 19 states to Frémont’s 11).

Flash forward to 1861. Now, the stage is set for perhaps Frémont’s greatest historical moment. Lincoln is the president, and the Civil War has broken out. President Lincoln taps Frémont as a major general and puts him in charge of the Department of the West. Frémont’s base is St. Louis in the acrimonious border state of Missouri. Here, it really is brother against brother, neighbor against neighbor. In this climate, Frémont tries to organize an army and plan a strategy to split the Confederacy along the Mississippi River.

When you actually study the opening phase of the Civil War, you have to marvel that either side was able to organize a military force at all. The air was poisoned with rage, politics and even, at times, indifference. Frémont struggled with the details of bringing a fighting force together (especially with generals in the field who were hungry for battle and not preparation). For Frémont, red tape and politics proved to be the real adversaries, not the army in gray. And in that environment of turmoil and uncertainty, Frémont went bold. On August 30, 1861, he issued the first emancipation proclamation, along with a few other measures to bring Missouri under control.

That’s right. Frémont freed the slaves of Missouri a full year before Lincoln issued his famous Emancipation Proclamation. What should be considered a noble stand against the institution of slavery proved simply naïve. Frémont, the man of action, was unable to understand the game of war, diplomacy and political deal making. Many decried Fremont’s stance as premature and foolish. However, fervent abolitionists (the outspoken wing of the Republican Party) praised his efforts. Wendell Phillips wrote that Lincoln was “not a man like Frémont, to stamp the lava mass of the nation with an idea.” And Henry Ward Beecher preached from his Brooklyn church’s pulpit that Frémont’s name “will live and be remembered by a nation of freeman.”

Frémont’s stance may have been morally right and inspired awe in more than a few Americans, but his timing was awful. In the general public’s mind, the country – specifically, the border states and many of the Northern states – was fighting a war for union, not a war over human bondage. In that light, Lincoln asked Frémont to rescind his orders, but the staunch anti-slavery proponent refused. Why should he – Frémont, the great trailblazer, the even greater survivor – cave to public opinion? He was a leader, so let him lead. And with that refusal, Lincoln dismissed Frémont, and his 100 days as head of the Union Army’s Department of the West came to a close.

OK, time is almost up. And we have only scratched the surface of this fascinating character. We haven’t even talked about his 21 days in office as the first senator of California, in which he introduced 18 pieces of legislation, including one to found the state’s public university system. Or his short-lived reinstatement as a Union general and his battles with Stonewall Jackson (like many Union generals, he did not fare well against the master tactician). We haven’t discussed his up-and-down career in railroad companies or his time as the territorial governor of Arizona. And we haven’t mentioned his final years mired in poverty and his attempt to rehabilitate and revive his reputation and fortunes with a memoir detailing his explorations.

In 1864, Frémont flirted with the idea of running for president again; however, he feared splitting the republican party and gave up his short-lived campaign.

So what happened? How did a great man like this pretty much disappear from our collective national memory? Frankly, the president’s assassination at the end of the war sealed Lincoln as a martyr of freedom. Frémont simply became a minor historical footnote in the discussion of slavery and emancipation. And more important, the country changed. Explorers were no longer national heroes because the frontier, that unknown and mysterious world to the west, had been thoroughly mapped (thanks to men like Frémont), and the nation was in the process of building cities and infrastructure. America had moved on.

However, if you travel out West today, Frémont’s impact is still evident. Just ask Judi Hall ’80, who lives in Portland, Ore., and travels across the Fremont Bridge on her commute to work. Or, talk to Mark Elliott ’96, who takes family and friends to Las Vegas’ Fremont Street Experience when they’re in town visiting (it’s the heart of downtown Vegas and boasts the largest LED screen in the world). And then there’s Susan Summerford ’94, the city planner for Fremont, Calif., a city of more than 200,000 people.

For our alums who travel or move out west, they discover the truth in Jessie Benton Frémont’s simple homage to her husband’s life and work: “Railroads followed the lines of his journeyings – a nation followed his maps to their resting place – and cities have risen on the ashes of his lonely campfires.”

Whether our alums know Frémont’s connection to the College of Charleston, well, that’s another issue. And perhaps in the future, there can be something on campus that marks his time here and memorializes some of his remarkable achievements. His connection to the College should not stay forgotten.

But until then, his prestige will simply remain in the many towns and counties, from New Hampshire to California, and the remote Western spots (rivers, mountain peaks and lakes) bearing his name.

Near the end of his life, crossing the United States by train, Frémont noted the contrast of travel to his earlier days and penned a few poetic lines on a scrap of paper. In these verses, we can clearly discern a man examining his life, pondering the bittersweet notion of greatness and legacy and asking himself, what happened?:

Long years ago I wandered here,

In the midsummer of the year.

Life’s summer too.

A score of horsemen here we rode.

The mountain-world its glories showed.

All fair to view.

Now changed the scene, and changed the eyes

That here once looked on glowing skies

When summer smiled.

These riven trees and wind-swept plain

Now shew the winter’s dread domain –

Its fury wild.

The buoyant hopes and busy life

Have ended all in hateful strife

And baffled aim.

The world’s rude contact killed the rose,

No more its shining radiance shows

False roads to fame.

Where still some grand peaks mark the way

Touched by the light of parting day

And memory’s sun.

Backward amid the twilight glow

Some lingering spots yet brightly show

On roads hard won.

Class dismissed.