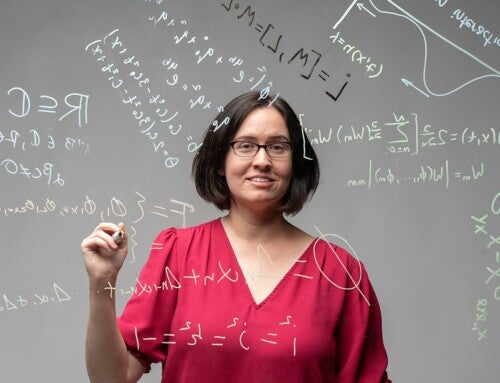

Max Kovalov, Adjunct Instructor of Political Science and International Studies and Eastern European scholar

College of Charleston Adjunct Instructor of Political Science Max Kovalov’s European Studies capstone started as an interdisciplinary course in European politics, history, and culture but current events have heavily influenced its content.

Kovalov, who grew up in Vinnytsia, Ukraine, is teaching a group of senior international studies majors about Europe at a time when the continent is facing “arguably the biggest security challenge since the end of the Cold War,” according to Kovalov.

RELATED: Check out the international studies major

“As a political scientist, I look for best explanations of political phenomena,” Kovalov said. “This is a good time to teach the European Studies class because students are interested in current events and they want to learn about the history and politics of Europe in light of the conflict in Ukraine. But as a Ukrainian it’s hard. Part of my country, Crimea, is annexed by the Russian state while another part is occupied by Russian troops.”

Evolving Subject Matter

The conflict Kovalov discusses began in late 2013. In November, Ukrainians protested against then-president Viktor Yanukovych’ decision to reject a EuropeanUnion (EU) Association Agreement. Yanukovych fled Ukraine in February 2014 after attempts to brutally suppress protestors and in the following months pro-Russian separatists in eastern Ukraine launched a violent war against Ukrainian central government to gain more autonomy for the region. There is significant factual evidence that Russia has been supporting the pro-Russian separatists by training military troops, providing weapons and money.

“The analysis of Russian media also suggests that Russia is engaged in an information war – in Russia and abroad – to mislead ordinary citizens about the nature of conflict in Ukraine,” Kovalov said.

As of September 5, 2014, the newly elected president Petro Poroshenko announced a cease-fire with the pro-Russian separatists. Meanwhile, Russian president Vladimir V. Putin issued a list of demands to maintain the shaky truce.

“Imagine if your house is invaded by your neighbor who comes in with weapons and takes over your living room,” Kovalov suggested, “Putin’s solution is, ‘Let’s allow the neighbor to take over the living room because he is already here. You can stay in the kitchen because you own the house, but do not try to come into the living room.”

For Kovalov, news about cease-fire is important. While the conflict provided thought-provoking conversation for his political science courses, the violence in his home country was distressing. The fact that Putin dictated many of the terms that would end, at least temporarily, the violence between the Ukrainian government and the separatist rebels is representative of a complicated balance between Russia and Ukraine, and between Russia and the West.

Kovalov elaborated, “Each time the U.S. and the European Union (EU) threatened sanctions against Russia, Putin would take a step back to show his good intentions by either moving Russian troops away from the Ukrainian border, or appealing to the separatists to delay a vote on secession, or accepting the legitimacy of the newly elected Ukrainian president. This has been going on for several months. When the EU announced its plan to introduce a new round of sanctions, Putin came up with this plan to solve the crisis that he created.”

Fragile Peace in Ukraine

With both sides of the conflict expecting the cease-fire to fall apart sooner rather than later, Kovalov realizes that Putin’s plan buys the rebels time to reorganize and strengthen their positions and it alleviates international pressure from Putin, potentially helping him avoid further EU sanctions.

It is challenging to fully grasp the motivations of Russian president. He has employed many tricks to keep the Russian public and the international community confused, and it’s worked. German chancellor Angela Merkel described Putin as living “in another world,” according to the New York Times.

“Putin has been moving troops into Ukraine, then taking them out, then moving them back, then taking them out again,” Kovalov said. “He’s moving weapons in and out, training rebels for combat, denying the presence of Russian troops in Ukraine, and describing active dutyRussian soldiers captured by Ukrainians as ‘volunteers on vacation.’ But he’s doing it incrementally to maintain uncertainty.”

Kovalov contended that these efforts by the Kremlin could be defined as modern warfare tactics. “This is a modern war that is very unconventional,” he said. His secretive strategies allow Putin to deny outright involvement with the separatist rebels, so that the Western governments have some uncertainty about his participation when discussing sanctions and further action.

Then and Now

When it comes to the EU’s politics of appeasing Putin Kovalov sees some interesting parallels.

“In my European Studies course, we are discussing the book Where Have All the Soldiers Gone by James Sheehan,” he said. “It’s about the events that led to European military action in both world wars, and the demilitarization of Europe that followed. It provides interesting context for current events when we look at how the rest of Europe is responding to the violence in Ukraine.”

Specifically, Kovalov explained, “WWII started when Hitler invaded Poland after first annexing parts of Czechoslovakia to protect the interests of ethnic Germans. That’s exactly the excuse we’re hearing from Putin now. In 1938, European leaders tried to appease Hitler instead of stopping him and they seem to be engaging in a similar type of appeasement today.”

Kovalov uses examples from the book and from current events to pose challenging questions to his class, like, “Where is the line for the West?,” “When is the right time for the EU and the U.S. to step in, and what exactly should their involvement look like?”

As a teacher and a moderator for these discussions in his course, Kovalov must reconcile both his identities – as a Ukrainian and as a political scientist. In the face of war threatening to tear his home country apart, this is not always easy. One thing is for sure, though; it will make for a fascinating semester.