Artist. Naturalist. World traveler. These are some of the adjectives that come to mind when you hear the name John James Audubon. One description of the 19th century painter that is often overlooked, however, is that of a businessman hustling to find paying subscribers to admire his art.

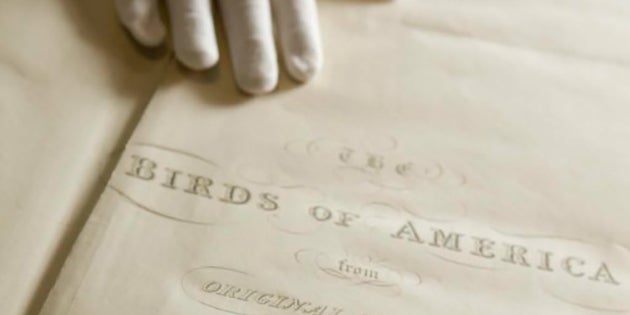

Now Special Collections at the College’s Addlestone Library can offer a glimpse into Audubon’s entrepreneurial side through a recent acquisition of a hand-written letter showing how he sold one of his most important works. Aside from being written by the namesake and inspiration behind the Audubon Society (yes, it’s that Audubon), what makes the letter so significant is that it references an original bound volume of Audubon’s iconic book “Birds of America,” which is also housed in the library’s Special Collections.

Harlan Greene ’74, the head of Special Collections, says the letter is more than just an interesting trophy. It’s an echo into the history of the book and helps connect the dots in the work’s journey to the College. And for those scholars looking to better understand 19th century printing and publishing, Greene says the letter provides information about the business and mechanics of publishing at the time.

“If you prize the work of someone like Audubon…any scrap of paper that’s in Audubon’s hand is going to be of interest,” he says, noting that the letter enhances the historical context of the book itself. “It gives an extra dimension.”

Much like the competitive world of self-publishing today, the document shows Audubon pushing to get his work into the hands of paying customers through a paid-to-order subscription.

In the letter, dated June 28, 1831, Audubon writes to the Newcastle-upon-Tyne bookseller, who was facilitating the sale of the two sets of his ornithological masterpiece, with instructions about the two copies – specifically that he paid for the binding of the books out of his own pocket.

“I sent to your care the volumes bound up of my work for Messrs Armorer Donkin & John Clayton,” he writes, continuing, “I sincerely hope they will be pleased.”

Clayton’s set of “Birds of America” was eventually sold in 1963 to ornithological painter John Henry Dick, who later bequeathed the book along with his considerable art collection and 881-acre Hollywood, S.C., property, known as Dixie Plantation, to the

This colorful painting shows the Carolina parrot eating a plant Audubon refers to as the cockle-bur.

College after his death in 1995. Beyond its link to the Audubon name, “Birds of America” is prized because of its rarity. Only 120 complete sets are known to exist, and those that have survived have sold for millions of dollars through high-end auction houses such as Christie’s.

David Cohen, former dean of libraries and academic services, met Dick on several occasions during the negotiations for his Audubon collection. By the time Cohen and Dick crossed paths, Dick, an avid admirer of Audubon’s work, was going blind. And yet, Cohen recalls how Dick could still describe Audubon’s images from memory, down to the smallest detail. Testing those skills, Cohen would describe a bird on any given page of Audubon’s iconic work. Every time he says Dick could identify the bird by name, its position on the page and the foliage on which it was sitting.

“It’s not so much the game we played that was remarkable,” Cohen says, “it was the evidence of his sensibility and sensitivity to the images as an artist.”

And now art lovers can better appreciate the amazing journey of these birds from their birth in the mind’s eye of a great painter, to the hands of John Clayton and John Henry Dick, to their current home among the annals of Special Collections.