Names – you find them everywhere on campus. They’re etched in stone, engraved in bronze and emblazoned on banners.

These names become intricately woven into the fabric of the College’s history and culture. Over time, however, the significance of these names fades somewhat, and they become just that – names, words without context.

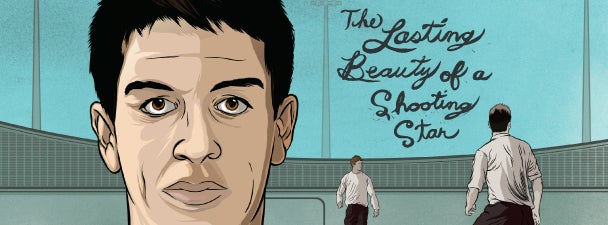

One of these names is Aaron Olitsky ’97, who is forever tied to a scholarship and a memorial men’s soccer tournament hosted at the College each fall.

“What’s in a name?” Shakespeare famously mused.

The answer – an entire life, full of complexity, romance, dreams, comedy and, at times, tragedy.

This is the story behind Aaron’s name.

by Jason Ryan

Illustrations by John Phillips

You’d probably have to get a magnifying glass out. And a small pick, or some kind of scraping device. A stick would even do if you’re desperate – just something to sort through the soil, rock crumbs and ground glass that seem to collect on every city sidewalk. Like the 49ers of old, you’re sifting through San Francisco dirt, hoping to spy glitter among the grit. Yet the prize this time is not gold, but flecks of glow-in-the-dark paint. It was put down a decade ago, just after Aaron Olitsky ’97 passed away.

There’s a good chance it’s all gone, washed away by wind, rain, stamping feet and spinning tires. But then again, there just might be a bit left. Jackie Sumell ’96 put down so darn much of that glow paint, tagging block after block with the number on Aaron’s soccer jersey: 18. She even made a contraption in her shoe that printed an 18 every time she took a step. Sumell ran for six miles after Aaron’s death, stamping his number up and down the hills of San Francisco, painting his presence in as many places as she could, trying to smother Shaky Town with luminescent reminders of a friend. The idea was that Aaron could see his number from up above – as could any jet passengers flying over the bay.

Surely, Aaron would have loved to have been in those airborne travelers’ company, seeking out new places and people. If nothing else, Aaron liked to move: across soccer fields and continents, around kitchens, through books and among friends. We all move, of course, but at different speeds, with more or less certainty of our direction and varying degrees of determination in our steps. Aaron, for his part, moved fast, with forceful grace, perseverance and passion. Aaron also never tired, which made him quite extraordinary.

At the College, Aaron was many things: tenacious midfielder, combative amateur Shakespeare scholar, budding chef and dashing Don Juan. He walked with a well-earned swagger. Very little, it seemed, was beyond his grasp, so long as he employed his trademark resolve to achieve a goal. At the College, he is officially remembered through the Aaron S. Olitsky English Scholarship and the Aaron S. Olitsky Memorial Fund, which supports the men’s soccer team and sponsors an annual college soccer tournament in Charleston. Elsewhere, he is remembered in the hearts and minds of his friends as a headstrong rebel with fierce convictions and an unforgettable independent streak.

Five years before his death, Aaron penned a poem for an English class. It was inspired by a trip he took the previous summer to Australia, where he played semi-professional soccer and tasted the fruits of the world.

I hear the plane engines purr daily

And the aphrodisiac smell of

Jet fuel is sneaking up to me, tickling my nose.

Inspiration buzzing like

The alarm clock for my first class.

Sick of pressing snooze on my dreams.

In short, the world promised possibility, just so long as he could stick around.

The Competitive Fire

Jet fuel, in fact, had tickled Aaron’s nose very early in life, whether he could recall such a sensation or not. He was born in Medellin, Colombia, on May 6, 1974, and immediately put up for adoption. Less than four months later, he was on a plane heading to a new country and new home as the first child of Atlanta’s Harvey and Judy Olitsky.

From the beginning, Aaron was a handful. He began walking at 9 months old and it wasn’t much longer before the energetic toddler tumbled out of a first-floor window at home, sending his family and visiting cousins into a mild panic before he was found to be OK. One of Aaron’s first brushes with danger, this would not be the last time he fell from a window. But even as a child, Aaron possessed an ability to make these thrills more endearing than alarming.

“Everyone was mesmerized by him,” says Judy Olitsky. “He was just so cute, you could never stay angry at him for long. No way.”

In elementary school, Aaron’s rambunctiousness was diagnosed as attention deficit disorder, and his parents allowed for him to be given Ritalin for two months. The stimulant didn’t work, and Judy – feeling guilty about medicating her son – ended the treatment. Years later, her self-reproach lessened when Aaron confessed to secretly spitting out all the medicine she’d given him.

One thing he did accept wholeheartedly, however, was his adoptive family; in fact, Judy remembers only one time when Aaron made a point of bringing his adoption up. She had been scrubbing a tub in the bathroom when a young Aaron snuck up from behind and hugged her.

“Are you sure I didn’t come out of your tummy?” he asked.

“Nooo,” Judy replied, dropping the scrub brush before sitting down with Aaron and rereading to him one of his favorite children’s books about adoption.

Aaron never desired to meet his birth parents, and indeed it was his identity as a Jew instead of adopted son that was of more relevance when he got older. Aaron’s Latin looks and dark complexion did not square with Jewish stereotypes, and his friends good naturedly teased him about his faith in the unique way that teenagers – for whom almost no topic is taboo, no difference off limits, whether in celebration or exploitation – do. For Aaron, the attention to his faith was positive. Upon his arrival, his friends would gleefully shout “Daru” at him, purposefully garbling pronunciation of “the Jew.” For his part, Aaron was no better, constantly twisting his sister’s name, Elana, into the very Georgian name of Duane.

If ribbing comes naturally to certain young men, so do competitive instincts. As Aaron matured, he continued to play soccer. In pickup games he could be fanciful, imagining himself a Colombian superstar. In tournaments, he was focused during gameplay, and furious when not victorious. Once, he snapped at his mother when she told him that he played well in defeat.

“I work hard every day so we can play well,” said Aaron. “I don’t like to lose.”

It was with that spirit that Aaron arrived at the College in 1992, and it was among his top priorities to make the men’s soccer team. Though he was a talented player in Georgia, the College had not awarded him a soccer scholarship. He’d have to make the team the hard way, as a walk-on. Javier Vivanco ’96, a former teammate and roommate to Aaron at the College, provides a little perspective on this endeavor, calling Aaron and the few other walk-on soccer players nothing short of amazing. Collegiate athletics, he explains, is a full-time job, and Aaron made the men’s soccer team by pitting himself against some of the best soccer players in the country.

Another freshman, Bruce Scott ’98, made the team as a walk-on with Aaron, and both were redshirted their first year. Such a maneuver – which allowed them to practice with the team but not play in games – is used by college coaches to develop players without sacrificing one of their four years of NCAA eligibility. Scott recalls the intensity of each and every practice, of Aaron and himself having to prove continually that they belonged on the team: “Lots of dogfights,” he says. “Everything was a competition.”

Because Aaron was so pesky a defender, he earned the nickname “The Fly.” One of The Fly’s favorite targets was Nick Frisch ’95, one of the better members of the team. Frisch quickly became annoyed with the freshman and his harassing style of play, characterizing him as “a little feisty fellow that was always a thorn in my side.”

One day, as they battled again over the ball, Frisch’s elbow went high and caught Aaron in the face, causing his nose to bleed. Aaron trotted off the field, had a trainer plug his gushing nostril and then hurried back into play. He had a message for Frisch: “If you think that’s going to stop me from marking you and getting noticed,” said Aaron, “you’ve got the wrong guy.”

After practice, while walking toward a team meal at the cafeteria, Aaron continued to press Frisch, though in a friendlier manner.

“I don’t know what your problem is,” Aaron told him. “My favorite band is The Cure, too.”

With this, Frisch caved, and the two became friends. So much so, in fact, that Frisch didn’t even take offense at the next thing Aaron said: Not only was he going to earn a spot in the starting lineup, he was also going to take Frisch’s girlfriend.

The Eye of the Beholder

The second time Aaron fell from a window was in Chicago. And it was a window not on the first floor, but the second.

Aaron had come to the Windy City to visit his high school girlfriend, Kim Dorazewski, who was studying at the Art Institute of Chicago. To sneak him into her dorm room, they hatched a plan to dress him in a wig and women’s coat. It didn’t work. So then Dorazewski went to her room alone, tied together a number of bedsheets, attached one end of the fabric rope to a radiator and tossed the remainder out her window. Aaron grabbed hold and hoisted himself up. As he reached the windowsill, however, his grip slipped. To Dorazewski’s horror, Aaron plummeted to the ground. Just as he’d managed as a toddler, though, he escaped serious injury from the fall.

The incident was a typical one in Dorazewski’s four-year relationship with Aaron – a bold, cocky and crazy boyfriend repulsed by conventionalism. Aaron had to find his own music from secret sources, says Dorazewski, and not listen to what was popular. He spurred her to take more chances, including persuading her to spend the night regularly when they were in high school. She’d sneak inside the Olitsky house, then back home again before school started, slyly evading Aaron’s parents and her own. During these nocturnal rendezvous, Aaron would make midnight meals, walk nearby neighborhoods with her in the darkness, take out family cars or watch beloved soccer-highlights videos over and over. Parents’ rules, Aaron the night owl decided, be damned.

“He had such a zest for life, he wasn’t going to let anyone or anything stop him,” recalls Dorazewski.

Sometimes, she says, his arrogance could be hurtful. But then he’d always redeem himself.

“It was tough being his girlfriend,” she admits, “but I knew everybody wanted to be his girlfriend … definitely the bad-boy image.”

Eventually, their relationship broke off, and Aaron turned his sights to Jackie Sumell, the girl he had promised to steal from Frisch at the College. To Aaron’s dismay, he bungled the heist. He overplayed his hand at first, singing to her in Craig Cafeteria, handing her poems and paper flowers and proclaiming publicly that Sumell was the girl he’d one day marry. Sumell, who was pursued by a number of soccer players, found the attention from Aaron annoying and his romantic pleas uncomfortably intense.

“He was not afraid to make a fool,” says Sumell, who – after ignoring Aaron for two years – found herself with him at a spectacular oceanside house on Sullivan’s Island, where Aaron lived with one of his soccer teammates. Upon arriving home, Sumell’s roommate, who had left a bit earlier, called her to talk about Aaron, and she didn’t mince words: “He’s really beautiful.”

Suddenly, Aaron was unveiled. Her roommate, Sumell realized, was right – Aaron was beautiful. The next thing she knew, Sumell was alone with him on the roof. The Atlantic Ocean spread before them. Its waves gently lashed the rocks that lined nearby Breach Inlet. A shooting star streaked overhead. They kissed.

Battle of Wills

The people Aaron respected most were those that were toughest on him – the ones who attempted to harness his energy and intellect, and whom Aaron fought fiercely. Into this camp fall just a few brave people: his parents and two opponents he met at the College.

One of these was English professor Nan Morrison, who taught Aaron’s Shakespeare course. Morrison recalls that the first time Aaron came to her office, it was to discuss a bad grade he’d received. He was courteous during the visit, says Morrison, but “it was the respect you show a tough competitor.”

They argued over Shakespeare. The next week, they argued again. Aaron wanted to read and write better, yet he yielded ground reluctantly to the scholar. Each week, he’d arrive at her office to renew their debates, with Morrison emphasizing the importance of an analytical perspective of the great playwright’s works and Aaron preferring to study the poetry in Shakespeare’s plays. Aaron’s sensitivity impressed Morrison.

“He could obviously feel the rhythm and the music and the beauty of the words,” she says.

After December’s exams, Morrison thought she’d seen the last of Aaron. But come January, there he was again in her class, enrolled for another Shakespeare course. He continued visiting her office each week, but this semester, recalls Morrison, there were fewer fights and more discussions.

A similar détente had occurred between Aaron and his parents. During Aaron’s teenage years, Judy often felt more like a warden than a mom. As Aaron became a young man, she transitioned back to mother. To her amazement, the adult Aaron – apparently unaware of the exasperation he often caused a mom who doubled as a schoolteacher – chastised her for not being more stern with him as a kid.

“Mom, you were not strict enough,” he said. “I got away with too many things.”

“Aaron, I had to sleep sometime,” Judy replied. “I couldn’t watch you constantly.”

Similarly, Harvey Olitsky enjoyed the end to a war he waged for much of Aaron’s childhood and adolescence. For so long, Aaron was the match to Harvey’s gasoline. Routinely they would lock horns, the smart-aleck kid versus the tough, retired Marine captain. As a Naval aviator during the Vietnam War, Harvey survived a number of crash landings in a helicopter. Such mishaps taught him humility, an attribute that, at first blush, it might seem Aaron was desperately missing. But upon close observation, notes Harvey, one could see Aaron had humility in good supply. Aaron appreciated and admired people who could do things that he could not. It was from these people that Aaron wanted to learn.

“That made it all worthwhile,” says Harvey, who retired from a 30-year career as a commercial airline pilot and now operates a lawnmower store. “He may battle with you, but at the end of the day he would fess up and say you were right.”

In 1994, while in Australia, Aaron wrote a journal entry about his dad, admitting he was homesick:

I just got off the phone with my father. I have always loved my father, but somehow I have not noticed it so much in my 20 years of life. … My father is not the one who simply created me sexually. My father is the one who can hurt me the most and the one who can love me the most. In the past it seems he has hurt me a lot, but in the big picture he was the one who wanted to give his unlimited love. Only two things would ever stand in the way of my dad’s love for me: my death or his death. Then the love becomes even more powerful. It becomes holy.

Revving the Motor of Perpetual Motion

Most people find it challenging enough just to walk on Charleston sidewalks, as the city’s notoriously uneven stone and brick pavers threaten ceaselessly to trip inattentive pedestrians. Aaron Olitsky and Javier Vivanco used these sidewalks as playing fields, juggling soccer balls up and down the streets, passing around parked cars, dribbling through the legs of passersby and chipping into stop signs. While parts of the student population trolled campus in search of parties on weekend nights, Aaron and Vivanco dueled under streetlights, constantly challenging each other to navigate the toughest downtown obstacles.

In soccer practice and during pregame warm-ups, the games continued. Most players were content to form a circle and pass the ball between themselves before games. For Aaron and Vivanco, gentle, static games of pass were not sufficient preparation for a match. After corralling all the other balls, one of them would streak into the circle of their teammates, snatch the remaining ball and jet off, initiating a game of keep away. The other players had no choice but to chase after the thief and get their hearts racing. They were running after madmen, however, and few could match Aaron’s stamina.

“He singlehandedly tried to prove the theory of perpetual motion,” says Scott, the teammate redshirted with Aaron. “He had a motor.”

Vivanco remembers returning from summer break one season to begin physical conditioning. On the first day of practice, in the August heat, the players were expected to run two miles in less than 12 minutes. Nearly every player had to train over the summer to beat the clock. Aaron, however, was the exception, working for a Charleston restaurant and enjoying the city’s nightlife. Yet he still finished the time trial in second place. His teammates, no slouches as athletes themselves, were impressed.

“He could smoke a pack a day,” says former teammate and roommate Paul Tezza ’05, “and run a marathon.”

Despite his physical talents, men’s soccer head coach Ralph Lundy would not let Aaron glide by. Lundy was the other person at the College unafraid to do battle with the young man, and their skirmishes were almost daily affairs. One thing known to get Lundy upset was Aaron’s penchant for performing trick maneuvers – such as back-heel kicks, nutmegs and rainbow passes – some of which were not always executed successfully. When Lundy got mad, Aaron was sent off the field to run the athletics complex as punishment. Lundy made sure to send him on his way immediately, for fear of breaking into a grin and losing his edge before him.

Ultimately, despite his antics, Aaron was an incredible asset to the team, and his tireless play an inspiration to his coaches and teammates. Aaron was a rather small player, yet he shied away from no one. As mirthful and carefree as he could be in other pursuits, he was humorless on the field and relentless in his pursuit of winning.

“He would never quit, no matter what the odds were. He would not stop fighting,” says Lundy. “When he walked across the lines, it was war.”

Aaron was a player during the most successful years of the College’s men’s soccer program, with the Cougars winning their conference each season he played from 1993 to 1996. For the last three of those seasons, Aaron scored the goals that put the College into the postseason, including a stunner in 1994 over Miami of Ohio. The Cougars were being pummeled by the RedHawks, and outshot about 10 to 1.

“They were bound to score a goal and put us out of our misery,” remembers Vivanco.

As the Cougars struggled to keep the score even, Vivanco received a pass and quickly played it far upfield to Aaron, against the grain of play. His best friend and roommate sprinted ahead, catching the Miami defenders off guard, as they had pushed forward in an offsides trap. Aaron, recalls Vivanco, was like a salmon swimming upstream, jumping waterfalls and struggling mightily against the current. With defenders trailing behind him, he collected the ball and focused his eyes on the net. He had just the goalie to beat, and Aaron put it past him, into the back of the net.

A Life Without Fences

The plan was simple: Pick Bruce Scott up and drive to Atlanta. Somehow, Aaron and accomplice Paul Tezza started to foul it up. The team was assembling in Atlanta to prepare for a flight to Holland, where they would train, play exhibition matches and watch professional clubs. Aaron and Tezza had offered to give Scott a ride, but first they told him they wanted to play a pickup game in the parking lot of a bank on Queen Street. Scott gave in to their wishes, but kept one eye on the clock. God help us if we’re late, he thought. Aaron may have become accustomed to the wrath of Lundy, but Scott didn’t want to get on Coach’s bad side at the beginning of such a big trip.

They played soccer for two hours. When they finished, the car keys were missing. When the keys were found and the trip under way, they noticed they were desperately low on gas. Then they made a few wrongs turns, even though Atlanta was home for both Aaron and Tezza. The comedy of errors was making Scott sweat: How did I get myself involved with these clowns? he remembers thinking to himself.

Yet, against all odds, Scott says, “somehow, in the nick of time, everything came together and was fine.”

Such close calls were routine for Aaron. He comfortably took risks others could not stomach, even if they were easily avoided. Sometimes this made his friends and family admire him. Sometimes, it infuriated them.

“He did things his way,” says Chris Rullet, a friend since childhood and frequent soccer teammate through high school. “It may not have been the easiest way, but he did it his own way.”

Also aggravating was Aaron’s flippant attitude toward danger and the way he explained away risky behavior. He often told his high school girlfriend, Dorazewski, that he wanted to die young. He told his college girlfriend, Sumell, that he wanted to die beautiful. He pointed out a crease in the palm of his skin to his father, explaining that he had a “short lifeline.”

Harvey got mad as hell about that, dismissed it as nonsense and countered that he couldn’t wait for Aaron to be a dad himself, and that he hoped he’d have three boys, each of them uncontrollable mini-Aarons who’d conspire to drive him crazy. Then Harvey would roar with laughter at the thought of it.

None of this, however, could change Aaron’s fatal convictions. In fact, if you take his scribbling seriously, his journal makes for interesting, if not morbid, reading. From an entry in 1994:

It takes a strong man to be unafraid of being by himself. I dread getting old and hope I have a peaceful early death because with age one becomes dreadfully alone, forgotten by society and away from his peers.

The consequence of such thoughts was a desire to absorb everything at once. In his love life, this could cause problems. Aaron strayed from girlfriends and often had to work hard to repair the damage. Sumell says their four years together were stormy, and that they enjoyed a “crazy, crazy love, and not always the healthiest.” Forgiveness could be a long time coming.

“Aaron had a lot of love for the world and for people,” says Sumell, who works as a social activist and conceptual artist in New Orleans. “To ask him to put up fences or borders around him would be asking him to stop expressing himself.”

One way that Aaron began expressing himself was through food. After graduating from the College, he worked as a cook at Magnolias restaurant on East Bay Street, and also as a DJ in Charleston clubs. Determined to make a living in the culinary world, he moved to Boston in 1998, where he worked at the restaurant Salamander. Hired as the garde manger to prepare cold foods, Aaron soon worked every station in the restaurant, including rotisserie and tandoori stations and a wood-burning grill and oven. In 1999, the restaurant’s chef and owner Stan Frankenthaler asked Aaron to accompany him to New York, where they cooked a seven-course meal at the prestigious James Beard House. It was a career highlight for Aaron, and helped him decide a few months later to pursue formal training at the California Culinary Academy in San Francisco. Someday, he dreamed, he would own and operate his own gourmet restaurant, or perhaps become a food critic, given his love of writing and poetry.

In December 2000, Aaron’s parents and sister joined him in San Francisco to celebrate Harvey’s 60th birthday. Aaron was in his second year at the culinary academy, and was making plans to come home to Atlanta soon to pick up a truck, which he’d drive back across the country to his apartment. As a birthday gift, Aaron contributed to a book of notes for his father and referenced the times they spent at the family cabin – which was on 35 acres of land on so-called Scenic Lake Harv in Ellijay, Ga. Aaron longed for a time that had passed:

Sometimes I wish you were still working around the cabin while I fished. Life was simpler than it is now. When I look back, I think that is the way life should be, relaxed in the fresh air, surrounded by nature, shoes and shirt off. We were just taking from God’s gifts and putting back what we took in the form of little brim [sic] and basses. I do not know what I am trying to say, but those kinds of memories pretty much sum it up for me. Life can’t always be that pure, but in the 60 years of your life there have been lots of pure moments. Try to remember them. I hope this is one.

When Everything Stops

The policeman strolled into Harvey’s store and said there had been an accident in Arizona, possibly with his brother. “Call this number,” he said.

Harvey dialed, then nearly broke. It was not his brother, but Aaron who had been in an accident. His son was dead. In the early morning hours of Feb. 14, 2001, Aaron had lost control of his truck on Interstate 40 while approaching Flagstaff, Ariz. The weather had been bad, with ice and snow, and the truck had flipped over.

Harvey hung up, left the store and went to find his wife. She was at school, in a conference with a parent and another teacher. He pulled her from the meeting and told her the heart-wrenching news. So began a long, sad struggle for the Olitskys.

“Life stops. Things are not going to be happy for you. Your plans are not going to come true,” says Harvey, who had lost a number of young friends in Vietnam decades earlier. One of them, Jim Nagle, was shown dead on the floor of a chopper in a famous war photo on the cover of Life magazine’s April 15, 1965 issue. It was the first time Harvey had seen anybody die, and the image has haunted him since. His son’s death, though, would weigh on him much more heavily. Aaron’s death was overwhelming. “I’m not the same person,” Harvey says.

He and his wife joined counseling groups, sharing sad stories in the company of other grieving parents. They all were, Harvey says, “part of that club you never want to belong to.”

They would grieve in separate ways.

Harvey attended Aaron’s graduation at the culinary academy later that year, but refused to go to the accident site. Conversely, Judy was too emotional to attend the graduation, but wanted to see where Aaron died.

Eighteen months after Aaron’s death, she traveled alone to the desert outside Flagstaff and visited the scene of the crash. Farmland and cattle pastures sprawled off on each side of the Interstate. She brought along a Star of David she had made, but the ground was too hard to drive a stake. Instead, she nailed the memorial to a fence.

Since her son had died, joy was absent from Judy’s life. When she imagined a healing place, it was somewhere that she could enjoy life again. It was a place difficult to reach, no matter how hard she tried to get there.

“When Aaron died, it felt as if all my senses were screaming for him,” she says. “I slept with his sweater, wore his socks, petted his books. I was craving the feeling of Aaron. My eyes burned from longing to find him on every street, in every group, on the TV screen. My lips hungered for the taste of his cheek. My lungs ached from inhaling so deeply to catch his scent. My ears rang from the strain of yearning to hear just one more time, ‘Mom.’”

Aaron’s death was no less horrible for his friends, including Chris Rullet, who knew Aaron at almost every stage of his life.

“He was like a soulmate to me,” he says, “and it’s been absolutely devastating.”

When Rullet boarded a plane from Los Angeles to Atlanta for Aaron’s funeral, he noticed he was aboard flight 1818. His randomly assigned seat was 18A. The coincidences were eerie.

Talk to any of Aaron’s friends and you’ll hear similar stories. After Aaron’s death, everyone grasped for No. 18 one last time, trying to establish one more meaningful memory or connection, to put a proper bookend on their relationship, to attach significance to interactions with Aaron they did not know would be their last. Aaron’s predictions of a short life had come true, and in the wake of his death his loved ones were scrambling to find something to hold onto, whether flight numbers, glow-in-the-dark paint or Aaron’s writings. Judy found this one written on a scrap of paper tucked into a cooking textbook:

You make me want to write down my thoughts.

My sleep is busy and awake,

The days are long and the five minutes with you are rapidly disappearing

like a drop of water on a hot skillet.

Singing, gleaming, running around as if not even touching the surface.

Our flesh touches, waiting patiently for more as we say farewell.

The last bit of steam floats to the top of my head and all that is left is this

Little brown stain in the pan and this burnt smell that is my life.

Good Night, Sweet Prince

At the funeral, people gathered to pay respects to the Olitsky family. Aaron, they recalled, was always willing to get in over his head. He was unafraid to fall from windows and had the guts of a poet, putting words down and drawing beauty

out of common experiences. He was a charmer, but he had substance.

Among the mourners was a wall of wailing women – assorted girlfriends from different times in Aaron’s life, some of them overlapping. Many of them were hysterical, and some oblivious to what romantic roles the others had played in Aaron’s life. Sumell was one of the women sobbing in that line, and she can’t help but smile now and think that, in a way, it was good that Aaron was not alive just at that time, or else he would have had a lot of explaining to do. Chances are, though, that she would have again extended forgiveness.

“You couldn’t stay mad at him,” says Sumell. “It was impossible. That was his superpower.”

These days, Aaron’s memory burns bright when some of the top collegiate soccer programs gather in Charleston each fall to compete in the Aaron S. Olitsky Memorial Classic. And when his sister’s 8-year-old son, named Aaron, runs wild across soccer fields in Alabama. And when a student at the College unlocks meaning in the same literature Aaron was introduced to as an underclassman, courtesy of the English scholarship endowed by the Olitskys in their son’s name.

When Aaron was around, everyone learned to take a few more chances, to step out of their shells, to be individuals, to breathe deeper and fuller, to gobble up life. Like that drop of water on a hot skillet, Aaron tore quickly through life, “singing, gleaming, running around as if not even touching the surface.” Then he was gone, too early to fulfill all his dreams, but late enough to make a lasting impact on the people he touched, including Sumell and so many other friends.

“Aaron Olitsky taught me so many things both through his passion for life and his death. He forced me to learn the hard way, through truth, through love, through passion and through loss. He did this for many and he should not be forgotten,” says Sumell. “He was a complex individual with many loves – and perhaps many lives. And if his parents manage to keep his legacy alive through a scholarship, it is a beautiful thing for the world, or – as Aaron would say – a buetiful thing (he was a terrible speller).”