You don’t have to tell Steve Johnson things move slower in the South. In Arizona, the artist painted in the morning and returned to a dry canvas after lunch time. In humid Charleston, it takes days for his paintings to dry, and that’s with fans steadily blowing across them.

You don’t have to tell Steve Johnson things move slower in the South. In Arizona, the artist painted in the morning and returned to a dry canvas after lunch time. In humid Charleston, it takes days for his paintings to dry, and that’s with fans steadily blowing across them.

The drawing professor isn’t used to having to be so patient. Coming from the desert, he isn’t used to seeing so many trees, either. Or, for that matter, marshes, rivers and ocean.

“Breathing the air here, I feel like my lungs are filling with water,” Johnson confesses.

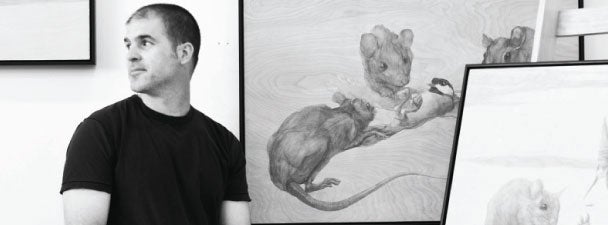

Don’t worry – Johnson isn’t drowning, but is instead floating at the top of Charleston’s art scene. Last fall, his exhibition From the Ground Up opened at the College’s Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art, alongside Bob Ray’s White Days Unswallowed. Johnson’s work features drawings and paintings of chickadees and rats antagonizing, if not torturing, each other. For Johnson, the animals represent lightness and darkness in the world. It is through this contrast that he hopes to explore all the grays in between, and the difficulty in maintaining rigid ideas and opinions.

Don’t worry – Johnson isn’t drowning, but is instead floating at the top of Charleston’s art scene. Last fall, his exhibition From the Ground Up opened at the College’s Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art, alongside Bob Ray’s White Days Unswallowed. Johnson’s work features drawings and paintings of chickadees and rats antagonizing, if not torturing, each other. For Johnson, the animals represent lightness and darkness in the world. It is through this contrast that he hopes to explore all the grays in between, and the difficulty in maintaining rigid ideas and opinions.

Mark Sloan, director and senior curator for the Halsey Institute, deemed Johnson’s site-specific installation of the show “spectacular.”

“Our audience loved his show,” Sloan says. “It was great to watch people going through the exhibition. At first, they seemed perplexed. Then, gradually, it dawns on them that the creatures are stand-ins for humans. Steve gives the rats and chickadees human characteristics, making them much more approachable. I enjoyed seeing people switch from a literal reading to a metaphorical one.”

Birds are old friends to Johnson. He grew up feeding sparrows with his grandmother. And, as a child, he once secretly tried to raise a barn owl in his bedroom closet, feeding it hamburger meat. That venture ended when wildlife officers showed up at the door.

While in junior high school, Johnson built an aviary beside his family’s home. Forty finches lived inside on the branches of a peach tree. And before recently moving to Charleston, he spent three years photographing and drawing geese living around a golf course pond. Perhaps it’s not surprising, then, that chickadees, which populate his backyard on James Island, star in his latest work. But rats?

Turns out that rats were a frequent visitor to his backyard, too, lured by a watermelon patch Johnson had planted. Annoyed by their frequent nibbling of his melons, Johnson set a trap in his garden. Upon catching one rodent, he prepared to kill it with a pellet gun before faltering.

Turns out that rats were a frequent visitor to his backyard, too, lured by a watermelon patch Johnson had planted. Annoyed by their frequent nibbling of his melons, Johnson set a trap in his garden. Upon catching one rodent, he prepared to kill it with a pellet gun before faltering.

“I just couldn’t pull the trigger. It was more his backyard than mine,” says Johnson. “It was the cutest rat, with big eyes. My heart just went out to this little dude.”

The rats in Johnson’s paintings are cute, too, save for the fact that they seem to be on the verge of harming the arguably even cuter chickadees. Johnson says the animals’ coexistence in his work was inspired by observations of wildlife in his yard – namely that bird feeders he erected to attract chickadees brought varmints, too, which feasted on spilled seed.

“By trying to attract the good,” he says, “I unwittingly attracted some less desirable characters.”

Ruminating on this irony, Johnson concluded that rats represent a societal underbelly, or Jungian shadow, that people tend to ignore. He felt compelled to depict it, and to create open-ended narratives in his paintings that force viewers to confront uncomfortable and undesirable parts of existence.

“There are aspects of ourselves we don’t want others to see,” Johnson says. “Things that we try to bury.”

He often works reductively, painting wood and then sanding it back in spots to recover its natural color. He chooses to use a limited palette, a decision he sees as a reflection of his time spent out West, where he witnessed bleached desert landscapes with color presenting itself temporarily and sparingly.

In his painting “Flying Rat,” Johnson provokes questions about ambition and limits. If the rat with homemade wings looks unnatural venturing into the airspace of the chickadees, a viewer might wonder if people are no less absurd through their use of helicopters, airplanes and rocket ships. In other words, is the flying rat adventurous or simply impudent?

Johnson notes that it has become commonplace for humans to want to climb higher and dive deeper, no matter the threat to the status quo and normalcy.

“It’s kind of built in,” he says, “that we shouldn’t be satisfied with what we have.”

But sometimes, Johnson says, such pursuits just result in people chasing their tails. Johnson’s ambivalence regarding ambition and achievement might inform his next exhibition. Then again, he might change course entirely.

“I haven’t figured it out yet,” says Johnson. “We’ll see what pops up in my backyard.”