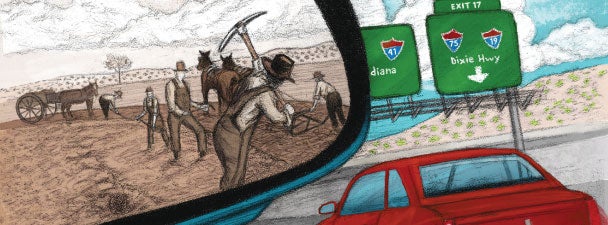

We always hear how it’s not just the destination that matters, but the journey itself. But have we ever wondered about the actual path beneath our feet – the road that makes both the journey and destination possible? One history professor has, and in so doing, she discovered a topic that stretches time and distance.

by Tammy Ingram

I have a hard time explaining to people why I write about roads. That’s right: roads. Highways. Routes. Thruways. Paths. Arteries. After nearly a decade of writing about the history of road building in the South, I know every synonym there is, but I have never developed a corresponding list of answers for scholars, students or, even worse, family members when they say, somewhat disingenuously, “Oh … roads? How interesting. … Um, why?”

So here’s a shot at answering that question, once and for all.

I’ve always loved to drive. My dad taught me how when I was 6 or 7 years old and then turned me loose with his old one-ton flatbed Ford when I was 8. With the tattered bench seat pushed all the way forward, I toured the back roads around our south Georgia farm with Scooter, my Chihuahua, perched on the seat next to me. When I was older (and legal), I ventured farther, this time with a stack of maps by my side.

My best memories are from those road trips – my first solo long-distance drive when I went off to college, a cross-country journey with an old boyfriend in his grandmother’s Buick Le Sabre and speeding across the Tappan Zee Bridge at 4 a.m. on the 1,000-mile drive home from grad school (when I looked to the left, I could see New York City lit up against the dark night sky). These days, I prefer two wheels: Along with my nerd posse – a small group of local chefs, photographers and videographers who let me tag along with them – I explore the flat, curvy back roads around Charleston on weekend motorcycle rides.

While this doesn’t fully explain my decision to write a book about road building in the early 20th-century South, I’m certain that it has helped me to understand how vitally important roads were – and still are – to farmers, businessmen, factory workers, schoolchildren and mere joyriders like myself. At the turn of the 20th century, roads dominated everyday life. They determined where people could and could not travel, as well as whether or not other people, goods, services and even ideas could reach them. Roads dominated conversations around the ballot box and the dinner table, but good roads eluded most Americans and virtually all Southerners. In their place, a jumble of muddy dirt routes blanketed the region like a bed of briars, full of dead ends and treacherous mud puddles just waiting to ensnare even the most careful traveler.

While researching migration patterns in the early 20th-century South for a graduate school seminar paper, I discovered that, around the turn of the century, farmers talked incessantly about roads. They complained that they couldn’t get anywhere because of bad roads. Their precarious financial situations became all the more precarious when they couldn’t get their crops to market. The “mud tax,” as they called it, cost them a fortune year after year. Local and even state elections turned into referendums on roads: Was the candidate a “good roads man”? If he wasn’t, or if he just wasn’t the best one, he usually lost.

Somewhere along the way, I stumbled across a reference to something called the Dixie Highway, a 6,000-mile network of interstate highways that looped from Lake Michigan to Miami Beach. It was the first interstate highway system in the country, but I had never even heard of it because few historians had ever written about it. In fact, they had written very little about road building during the early automobile age at all. Considering how popular books about cars have always been, I was surprised that no one had thought to question how we ended up with roads on which to drive them. It was as if everyone – historians included – assumed that roads had always been there. Or perhaps they just assumed that it would not be an interesting story.

But I knew that the story of road building had captivated farm families a century ago. When the Dixie Highway was first proposed in 1914, most roads in the South were entirely local. They looked like spokes on a wheel, starting at the nearest railroad depot and branching out only as far as the nearest farms. There were few links between towns and cities and even fewer across state lines. Roads were entirely local in scope, and they fractured the countryside into a series of adjacent yet isolated communities.

When I looked more closely at a map of the Dixie Highway’s extensive, winding route through my home state of Georgia, I realized that it passed through the southwestern edge of the agricultural “Black Belt,” very near where I grew up. The original roadbed was long gone, but having spent countless hours navigating the still-unpaved back roads of south Georgia, I thought I had some idea of just how remarkable a thing the Dixie Highway must have been. There, in the midst of a primitive system of roads, was an interstate highway network that linked people like my great-grandparents, one set of them small-time cotton farmers and the others sharecroppers, to new markets for new crops like peanuts, peaches and pecans. While they probably never ventured much farther than the state line, the Dixie Highway could have taken them to distant and unfamiliar locales like Chicago to the north and the bustling new resort city of Miami Beach to the south. They could have made the 250-mile drive to Atlanta in a day, when before it would have taken twice as long on multiple passenger trains because no major lines passed through the tiny county where they lived.

Maybe I’ve had a hard time explaining why I write about road building because I don’t remember deciding to write about roads. I just realized how important they had been to the people I was already writing about, and that was enough to make them interesting to me. Over the past 10 years I’ve learned how the transportation system we take for granted today evolved out of hard-fought political, economic and cultural contests. They determined the outcome of local, state and even national elections. They transformed the lives of ordinary Southerners like my grandparents and great-grandparents. They transformed the nation. And they laid the foundation for the modern transportation system we have today.

While modern technologies like the Internet and mobile phones link us in ways people a century ago couldn’t have imagined, we’re still dependent upon roads. I see it every time I get into my car or hop on my motorcycle: long-haul truckers carrying much of the food and retail goods trains used to carry, because they’re cheaper, faster and have more flexible schedules; school buses carrying children to modern classrooms; and residential neighborhoods sprawling far from city centers and railroad depots because cars and buses take us to our jobs every day.

The lesson my Dixie Highway research has taught me is one I carry into the classroom with me every day: Ordinary things are interesting if you have enough curiosity to ask questions about them.

– Tammy Ingram is an assistant professor of history and the author of Dixie Highway: Road Building and the Making of the Modern South.

Illustration by Dave D’Incau Jr.