Edgar Allan Poe wrote, “The boundaries which divide Life from Death are at best shadowy and vague.” As one student discovered, that couldn’t be more true than in this iconic Charleston graveyard.

By Phoebe Doty

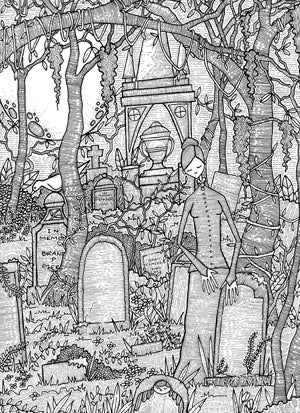

Overgrown with trees, shrubs and vines, the Unitarian Church in Charleston’s graveyard at night inspires frightened looks over visitors’ shoulders, wary glances around headstones and quickened heartbeats. Wild nature overwhelms decrepit old headstones, cracked and worn away from years of the sun’s rays beating down on them. Vines, like slithering green snakes weaving their way up from the shadowed ground, overtake the graves and claim them as their territory, while gray Spanish moss hangs perilously low from the crape myrtles. The vegetation of the cemetery, wild and enveloping, tangles itself around trees, wrought-iron fences and old headstones. Although the Unitarian Church’s graveyard, nestled among posh Old-South antique shops on Charleston’s King Street, meets the spooky criteria for a ghost tour’s tourist trap, the overgrown graveyard is home to more life than death. It’s a Southern jungle for the dead.

I begin my exploration of the graveyard on a humid August afternoon, sweat sticking my clothes to my skin, the air heavy with the smell of horses from the passing carriage tours. Breaking away from gaggles of tourists walking with sloth-like speed, I enter the graveyard. Suddenly, I am immersed in green tranquility. Standing just inside the gate, I see before me a romantically morbid garden of South Carolina’s native plants. Thriving in between the remains of faded headstones, some dating back to the 18th century, wildflowers and bushes extend up to the heavens, a living symbol of hope rising above markers for the dead. Little lizards scurry by my flip-flop feet on their short dinosaur-like legs. I go in thinking I’d find tourists with cameras ready for ghosts. Instead, I find life. Nature at its most energetic.

Since the church’s founding 200 years ago, the plants grow wherever they please, as long as they don’t interfere with the pathways. This peculiar design, based on the free-flowingly scenic layout of Mount Auburn Cemetery, was envisioned by Caroline Gilman, who moved from Boston to Charleston in the 1820s. Walking along the carefully manicured pathways, stopping often to watch blue jays perched on oak limbs, I watch the animals and plants in the graveyard reaching up to the celestial heavens, asking a higher power for peace: living symbols of the religious fervor that inspired Mrs. Gilman to create such a unique landscape.

Unlike many of the visitors on the ghost tours that make this graveyard a regular stop, I notice not death, but wild, sinewy vines and tree limbs: physical signs of eternal life. Here are solid beams of gratitude coming up from the ground, not desperate corpses reaching up to visitors. Even if ghost tours traipse through the cemetery searching for moaning ghouls or sighing ghosts – souls waiting eternally for a lost love or for revenge – in my mind, this graveyard is only home to peace and the beauty of life, promising for more to come in the next.

Making my way deeper into the grave-filled jungle, I stop and chat with one of the church volunteers caring for the grounds. “We put in a lot of work to make it look like no work is done at all,” he said when I asked about the graveyard upkeep. And I notice this. Even with the hanging moss and tall grasses encasing the headstones, the pathways are clear for visitors. On these pathways I examine the unbridled nature of the tiny leaves dancing on breeze-blown ferns and crape myrtles in the graveyard, little blooms of life on sacred ground dedicated to the dead. A macabre bouquet for the graves.

This bouquet supposedly helps cover the unmarked grave of Annabel Lee, the subject of Edgar Allan Poe’s famous poem with the same name. I fruitlessly looked for her grave marker, knowing I would find none. Guides of ghost tours love to frighten tourists with Lee’s story, although she is a fictional character. Tour guides say that Lee, to her father’s dismay, had an affair with a poor sailor. When she died of yellow fever, her father buried her in an unmarked grave in the cemetery to keep her lover from finding her. Even though there is no record of Lee’s living in Charleston, ghost tours still tell visitors that the Unitarian graveyard is one of the most haunted cemeteries in Charleston, and she is their most-seen ghost. Guides maintain that she waits eternally for her sailor in the graveyard, hoping to find her lover. Although just a hoax, this message of eternal love rings true in the Unitarian cemetery. Lee’s love for her sailor is captured in the true love of the couples buried together in the graveyard, resting together forever under camellia trees adorned with pink blossoms and dangling Spanish moss.

Winding my way out of the cemetery, I pause to look back at the headstones, little dark faces in a sea of green. In lines, all different heights, colors and degrees of wear. A bulky one catches my eye: a joint headstone for a couple whose epitaph reads, “They were lovely and pleasant in their lives together.”

Truly, this overgrown graveyard is home not to ghouls, but to grace.

– Phoebe Doty is an English major. Her essay was originally written for an advanced composition course taught by Bonnie Devet, professor of English and director of the Writing Lab.