by Mark Berry

Photography by Andrew Cebulka; illustrations by John Phillips

It was really just by chance that these four old college friends bumped into each other 20 years ago at Charleston’s Hibernian Hall on Meeting Street. Father James Parker, Charles Foster ’50, Robert Chitwood and George Nelson ’51 caught up as if no time had passed between them, laughing about the old days, remembering the college dances and socials they had attended back in the ’40s right here in this white-columned

Charleston landmark. By the end of their conversation, they marveled at the providence of coming together, especially at a place they all knew so well, a monument of sorts to their own collective youth. They vowed from then on to get together once a month for lunch, with the hope of bringing other college friends into the fold.

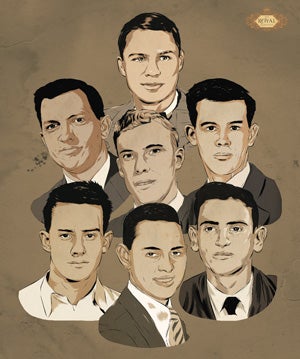

And they were successful. From 1993 on, that original group of four grew to include a changing cast of College alumni and former students from the late ’40s and early ’50s. Men such as Ed Cochran ’53, Louis Condon ’50, Bill Cronan ’49, Archie Jenkins ’55, Keith Marshall ’49, Irvin Molony, Billy Moore ’50, Ernie Nelson ’49, Arthur Ravenel ’50, Ed Schwacke ’51, Slug Slaughter ’52 and Sonny Westendorf ’51. “Over the years, we picked up some,” Nelson explains. “We would lose somebody; then we would pick up another. Our latest iteration of seven has been pretty consistent for about six or seven years.”

At first, the informal meeting of these old Maroons took place at Jimmy Dengates private club on Rutledge Avenue. “We loved it there,” recalls Father Parker. “But they turned it into a sports bar with 8,000 television sets and a lot of younger people that made a lot of noise. We’ve tried different places over the years. About a year ago, we picked Page’s Okra Grill in Mt. Pleasant.”

Whatever restaurant they may choose to share a meal in, one thing remains constant: They are there together. And always around that table is a vast wealth of knowledge and experience, more than half of a millennium of it. Their lives span a remarkable time in American history – valleys and peaks that today’s generations could only understand by living it. Of course, these seven men will tell you it was a simpler time then, but don’t believe them. Their world was tremendously complicated.

For they are children of the Great Depression. They saw a very different Charleston, decades before it was the No. 1 tourist destination in the world. They knew it as a once-great city scratching, clawing its way back, a jewel dulled by war, earthquakes and economic collapse – but a jewel, nonetheless. They knew a segregated South and, like most, believed it to be just the way things were – until it wasn’t. They remember listening to the radio for the latest news reports coming from Europe, following the war like a daily serial. And they looked out on an Atlantic Ocean that was being terrorized by marauding Nazi U-boats, knowing that the lives of some of their family, friends and neighbors were in great peril. In their time, victory was never a foregone conclusion. And yet, they will all admit that they are the luckiest men – to be born when and where they were.

Because they are a ’tweener generation: too young for service at the beginning of World War II and just old enough – and just savvy enough – to select their branch of service during the Korean War’s universal military draft. As James Edwards ’50 likes to remind Foster, both of whom served as teenagers with the U.S. Maritime Service at the tail end of “The War,” as they call World War II, “You don’t realize how close we were to extinction.”

But they survived – and thrived. The rise they made in their respective careers mirrors, in many respects, the ascension of the United States as a world leader. They worked hard and took advantage of whatever opportunities came their way, whether it was through their own initiative or just good luck. And to a man, they agree that you need both to be truly successful.

Now, when they look back on their formative years in Charleston, talking over lunch specials and glasses of sweet tea and ice water, those black-and-white memories are slightly faded, perhaps a little frayed around the edges by time and nostalgia. They talk fondly of a Charleston filled with sailors and soldiers, forgetting the brawls and vice squads. They recall hours hanging out at the Cistern, watching the pretty girls go by, and seem to exhale a unison sigh. They laugh about their favorite college drinking holes – the Anchor, Papa Kelly’s Spaghetti House, the Rascallop – and about West Street, downtown Charleston’s one-time red-light district located only a few blocks south of campus (and where Biemann Othersen ’50 now lives – to the amusement of everyone around the table).

They have all seen much, done much, and they swap stories, jokes and jabs with the natural confidence and easy humor of great adventurers now safe at harbor – and, most important, now home among friends.

[divider_line]

George Nelson ’51

Nelson enjoyed a remarkable career in medicine and academics. He received his Ph.D. in biochemistry from the Medical University of South Carolina (then, the Medical College) and later earned his M.D. from the University of West Virginia. Winner of a Foundation Prize Award for his work analyzing amniotic fluid to determine the likelihood of a baby developing respiratory distress syndrome, Nelson taught at several universities and retired a professor emeritus from the Medical College of Georgia.

on his first semester: Dean Jennings wanted to talk with me. I went in there, and he said, “Son, I’ve been dean here for 10 years, and I’ve never had anybody get four As and a D. You got an A in every subject that seems hard to me, but you got a D in history.” I told him, “I couldn’t stand that guy, and he couldn’t stand me.” Dr. Jennings said, “Well, I’ll tell you what. Why don’t we just drop that. I don’t like that on your transcript. I’ll schedule you next year with this other guy.” I then made a B the next year.

most embarrassing moment: I only did this one time. I went into Mr. McGlaughon’s Latin class unprepared. I don’t know why I even went to class that day. We only had maybe six people in the class. I knew I was going to be called on. I never went unprepared again.

school assembly: On the main floor of Randolph Hall, there’s an auditorium with a little stage [Alumni Hall]. We had, maybe once a month, a student meeting or something. And it opened with a prayer. We sat facing the north, but during the prayer, everyone stood up and turned around and faced south. I had never seen that before. I think it was President Grice that led that prayer.

athletics experience: When I went to the College, they had a freshman basketball team called the Baby Maroons. They said, “Come on, man.” So, I played. When varsity came along, I tried out. There were 13 uniforms for the team, and I got No. 13. I really wanted to go on the trips. The team traveled to Florida and the northern part of the state. I enjoyed the team very much. I was 5’7″ back then. If I got to play, it was a bonus. My senior year, I played quite a bit. I was the first guard to go in.

on his last semester: My senior year, Dean Jennings called me into his office again. “I’ve got another problem with you, George. And I’ve never had this one before, either. You’ve taken enough Latin that you qualify for the A.B. degree, and, as a chemistry major, you obviously qualify for a B.S. degree.” “What’s the difference?” I asked. “The A.B. is written all in Latin and the B.S. is written in English. You have a choice.” So, I got an A.B. degree with a chemistry major. I don’t think anyone had done that before.

advice for today’s college student: I think students ought to dress better. I wore a sports coat to school every day. Today’s students dress kind of sloppily. If I see children in the third grade and they’ve got some sort of uniform, I have a feeling that they go to a higher-class school. It’s just an impression I get. I don’t know if that is right or wrong, I just have a feeling.

[divider_line]

Charles Foster ’50

Foster’s life exemplifies the power of a liberal arts and sciences education to give you the flexibility and know-how to pursue various – and vastly different – careers. A veteran of the U.S. Maritime Service (World War II) and the Coast Guard (Korean War), Foster later worked for the Central Intelligence Agency for more than a decade and then founded, in 1969, the Charles Foster Company, which focuses on staffing and recruiting needs for a variety of businesses.

on his college days: I studied history and economics. I didn’t really excel at anything. I was always a shy sort of guy. The limelight didn’t particularly appeal to me. I just wanted to see the world and maybe write about it.

the spy experience: I was working in the Census Bureau in Washington, D.C. In those days, the early ’50s, the Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool had several big Quonset huts near it, which housed several government agencies, like the Veterans Administration and the Commerce Department, where I worked. Well, Bill Cronan and I were in line for lunch one day and there was another line that I hadn’t seen there before. And there were these attractive, well-groomed people and good-looking girls there. “Who are these people?” I asked. Bill said, “Those people are CIA.” And I told him, “I want to be in that line.”

I sent them my résumé. In a couple of days, they called me. They didn’t tell me why. It was a short interview. I didn’t get much out of them. I found out it was something to do with communication, and they were interested in my radio school and electrical school experience with the Maritime Service.

To make a long story short, I enlisted into the Coast Guard at that time (I was being drafted into the Army), but when I got out, I put my application in with the CIA again. They may have forgotten me, but I didn’t forget them. And the CIA took me. Two weeks before they were shipping me out to northern Japan, which, honestly, I wasn’t really looking forward to – I ain’t one for real cold weather – I was reassigned and they sent me to England. I was an office manager or personnel director for a small group of individuals. I think spy would have been the wrong term. I was just a personnel man.

his Oxford days: While I was over in England with the CIA, I figured I would use my G.I. Bill out of the Korea thing. I went to Oxford and they bent over backwards to process me through. They told me I would fit in at Nuffield College. Max Beloff, who had written volumes about international affairs, was my tutor for a year and a half. He treated me just great. [Lord Beloff is considered one of Britain’s foremost historians, political scientists and politicians of the 20th century.]

returning home to found Charles Foster Company: Something about a Charlestonian is sort of like an Italian: At some point in your life, you have to come home – and you come home. That’s what I did.

[divider_line]

Father James Parker

Because Father Parker wanted to major in Greek, which the College did not offer as a degree program at the time, he transferred after his sophomore year – on the advice of his CofC Greek professor – to better prepare him for seminary in the Episcopal Church. After three decades of preaching in Georgia, Indiana, Illinois and Tennessee, he led the charge of many Episcopal priests converting to the Catholic Church in the early ’80s. With his conversion, Father Parker became one of the first married priests in America. After that, he worked closely with Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) at the Vatican and Cardinal Bernard Law in Boston, helping to process the Episcopal priests joining the Catholic Church, before retiring to Charleston in 1985.

his childhood in Charleston: I lived on George Street, between King and Meeting streets, in one of the biggest houses there. It was the nicest house on George Street: a three-story, Victorian-style home. The man who bought it from my parents tore it down. That was before the City could stop things like that. Today, that piece of property is a gravel parking lot owned by the College [for years, that property was the location of the Great Wall of China restaurant].

Everything we needed was right there. Automatic Grocery was near there; the barbershop was near there. And the Gloria Theatre [now the College’s Sottile Theatre] was just down the block. I saw Gone With the Wind there in 1940. Down the block was the Garden Theatre [now Urban Outfitters]; it showed Ronald Reagan movies, not the cheap Westerns.

thoughts on the College: The College was here from the beginning, when there were only just a few colleges in America. The College offered something that I think was more academically superior than the few other schools around. It remained insignificant beyond Charleston. It didn’t become Harvard or something like that, but I think it’s certainly in that category.

The College was very academically precise. Comparing it to others, the College was more intellectual, more academic. It was very concerned about its students and expected a lot from them. You weren’t just there playing a game.

on the College’s geographic diversity: There weren’t many out-of-town students, and they lived in the upstairs of the gym [today’s Silcox Center]. There were close to 250 students then, so it didn’t really bother us, as we didn’t have enough sense about it.

advice for today’s college student: The education is the major thing they are there for – not the lifestyle they may like in college. And they should dress decently to properly show the respect for the education they are getting. I have to say, driving through the campus these days, I see those students with the clothes they wear. It’s disgraceful. We wore neck ties and a jacket. I look at these girls, wearing pants that look like they were spray painted on. During my college days, I never saw a girl in slacks. They wore skirts and looked decent.

[divider_line]

Fred Wichmann

Like many of his generation, Wichmann wanted to see the world – and he did. As a 16-year-old high school student, he enlisted in the Maritime Service toward the end of World War II and traveled to Europe. Later, when he was at the College, he was in the U.S. Navy Reserves and was called up for the Korean War. Because he hadn’t finished his degree yet, the Navy would not send him to Officer Candidate School, so rather than be a swabby, he instead enlisted with the Air Force and was sent to England. After some grand adventures, both on and off the water, he eventually returned to America and has enjoyed a successful 40-year real estate career in Charleston.

losing his ship: In the ’50s, I bought a teak-plank, 65-foot yawl named Colleen, built in 1903. I had planned a trip to Spain on her with some friends. It was January, and we ran into a 60-knot sou’easter and lost our rudder. The wind pushed us up into the Irish Sea, which was not a very happy place. A Dutch refrigeration ship eventually took us, and we abandoned ship, leaving all of our clothes, just everything we had, on the boat.

It was nasty and dark. I had lashed some lights on her so we could see her. A French fishing trawler came along and put a line on her and towed her back to France. The Dutch captain dropped us off in Belfast. I went to the American embassy there to see if we could get some financial help because I didn’t have any money. The American ambassador pulled down some big book and said, “Stranded yachtsman? I don’t see any place here for that.” Anyway, he loaned me $500 from his personal pocket.

I eventually got to Orleans, France, where the fishing trawler had towed my boat. The fellow there was claiming the yacht for himself and his crew, and my boat was in a guarded marina. I went to court, but they told me that the French crew had saved the boat and I could pay them $25,000 for salvage. I didn’t have $25,000 and I figured I had better get on my way, which is when I decided to come back to America.

His college days: Everybody knew everybody. I was a member of Phi Delta Kappa, a local fraternity. I studied German because my father was German, who was a lighthouse keeper at Cape Romain. I also wrote a weekly column called the College Quill for the News & Courier [the precursor to today’s Post & Courier]. That column was about what was going on at the College: college parties, somebody seen with so and so. It was not too widely publicized that I was writing it. I may have not used my real name on it. My main ambition was to be a writer because I wanted to write books and novels. I liked Faulkner; he was really a man.

Advice for today’s college student: Consistency is the key to success. Stick with something until you get it mastered. Maybe it’s a language problem, a mathematical problem or a historical problem, whatever – keep working until you get it right. I’ve stuck with this real estate business all these years [since 1973], and I think I have come a long way with it.

[divider_line]

Irvin Slotchiver

Slotchiver, known simply as Slotch to his friends, was one of the first tax lawyers in South Carolina. A veteran of the Korean War, he served stateside as a private in the U.S. Army’s Finance Corps before returning to Charleston to begin his legal career. Still working today in his office on State Street, Slotchiver, the 2014 S.C. tax lawyer of the year, has represented pretty much every significant business, big and small, in Charleston over the course of the last half century.

the path to law school: I left the College at the end of my third year. I had one semester left. A good friend of mine, William Duncan – we called him Red – asked me if I would take a ride with him to Columbia. On the way up, he said he was registering for law school. Meanwhile, I was a history major, and I had no idea what I was going to do with that history degree. My father owned a shoe store in Charleston, and I really wasn’t interested in going into the shoe business. When we got to the law school, I asked a few questions of the dean and decided to sign up as well. At that time, law school only required that you have three years of college. It all happened spur of the moment.

going into tax law: I graduated law school in an accelerated two-year program right before my 21st birthday, and I came to a quick realization that no one wanted a lawyer who wasn’t even an adult.

I then went to Duke Law, but they didn’t have tax law, so I left at the end of the semester. I was told the key to tax specialty was accounting, which made a whole lot of sense to me. I then applied to two schools: Harvard and Penn. Harvard asked me to come up for an interview, and I didn’t have money for the fare. The Wharton School accepted me, so that’s where I went. I went up there for an initial interview after I was already accepted, and the dean there looked at my record, and his face lit up. He said, “College of Charleston.” They knew it.

on tax law: Tax is mostly a theoretical thing. It may sound black and white and boring, but if that’s what comes across to people trying to practice tax law, then they’re having no fun. It’s creative. People walk in with a problem and what they want to know is an answer. You could say, “Well, here’s the book, and the book says so and so,” but that’s not the answer. It’s a lazy man’s answer. Tax law is like a crystal. Every time you look into that crystal, just give it the slightest motion, and you’ll see something completely different that you never saw before.

And know that your practice changes every 10 years or so. It just moves, and you have to adjust. You go with the flow because it’s really about whatever your clients want and need you to do.

advice for today’s college student: Follow your intuition. That’s what has worked for me. I can’t honestly say I had a plan. Things just happen. Get a good education. What I’ve got has been wonderful and has given me a wonderful life. Know that things will evolve and be honest to yourself – you can’t go wrong then.

[divider_line]

Biemann Othersen ’50

Othersen is a pioneer in South Carolina medicine. A former president of the American Pediatric Surgical Association, he was the first pediatric surgeon in South Carolina and established the pediatric surgery department at the Medical University of South Carolina, where he taught and worked from 1965 to 2001 and where he is still active with its residency graduate program.

on going to the College: Initially, I wanted to be an engineer. I applied to Clemson and had been accepted and had a small scholarship. This was 1946, when all of the veterans were coming back from the war. Every university was giving first choice to veterans. They told me I would have to defer a year, so I decided to go to the College in the meantime. Of course, there were no engineering courses, being a liberal arts school, so I took biology and a lot of pre-med courses. I liked it so much that I stayed.

When I think of the College, I picture a very happy place. We got a great education for very little money. I came from a family of six children. We didn’t have much money so I had to make money to go to school. Because I was a resident of Charleston, the City paid our tuition – something like $300 a year. We only had to pay our lab fees, and I had a scholarshp for that.

in the classroom: I particularly enjoyed Dr. Towell [Edward Towell ’34, who’s the namesake for College’s Towell Library]. He was a tough professor. He was a nice guy, but he was very dignified. No one misbehaved in his class. One day, in his comparative anatomy course, we cut the paw off a dissection cat and dipped it in black ink. We took it and made tracks right along the blackboard, up the wall and halfway across the ceiling and stopped. Dr. Towell came in, looked at the tracks, didn’t say a word about it and started lecturing. If only we had used half of the energy that we did on pranks on our academic pursuits.

between classes: We loved pick-up basketball games. We would rush over to the gym and would play – often without changing our clothes. We wore ties most of the time. We would come back to class all sweaty – smearing the ink on our notes.

going into pediatric surgery: I always liked dealing with children. If you did everything right, they did well. They just popped back. And they didn’t do a lot of moaning and groaning like adults. At that time, around 1965, people didn’t think you needed special surgeons for children. In fact, no one encouraged me to come back to South Carolina. General surgeons here saw me as a competitor for their practices. They would say, “There aren’t that many children.”

I started MUSC’s pediatric surgery department from scratch. For 14 years, I was by myself. That meant, anytime I was in town, I was on call. In fact, when we got beepers for the first time in the ’70s, it was a real emancipation for me. Because for years, even if I wanted to drive around with the family on Sunday afternoons, I had to stop at phone booths along the way and check in.

[divider_line]

James Edwards ’50

Edwards is one of the most distinguished and accomplished alumni in the College’s history. Dropping out of the College before he even attended his first class, Edwards left school to seek adventure with the U.S. Maritime Service toward the end of World War II. A few years later, he returned to campus and studied chemistry in preparation for going to dental school and a career in oral surgery. In the turbulent ’60s, Edwards decided to get involved in politics, and his star quickly rose. In 1972, he was elected a state senator, and just two years later, won an unlikely bid for the state’s top office, becoming the first Republican governor in South Carolina since Reconstruction. He was governor for four years (the limit at that time) and later became President Ronald Reagan’s secretary of energy. In 1982, Edwards took the helm of the Medical University of South Carolina, where he was president for 17 years. In 1997, Edwards was inducted into the South Carolina Hall of Fame.

dropping out: When you’re 17, you don’t have very good judgment. I busted out of the College and went to sea. I started off as a messman – the dishwasher on a troop ship. It can’t get much lower than that. I then became an ordinary seaman and worked my way up.

One of the things I did, I was on a hospital ship. When I was off watch duty, I would go down into the medical ward and visit the wounded. As merchant seamen, we took the troops to the beach and left them. They did the rest. Seeing the results of war had a profound effect on my life.

I was fortunate enough to get on board the USAT George Washington. I expressed interest in learning navigation, rules of the road and seamanship. I got promoted to acting junior third mate, and I was on the bridge, with all the books and instruments, and the senior men taught me. I studied for 18 months and then took a long, arduous exam in New York. I passed it and got my license – an unlimited license, which is the best you could get. I was very proud of it. That was my first real accomplishment. I brought my license home in December 1946 and hung it on the Christmas tree for my mother and father.

coming back: When I told my father that I was going to come back to the College and get my degree, he said, “You’re just wasting your time. You shouldn’t do that. You’ve been successful at sea, so you ought to stay at sea.” It made me so mad. I couldn’t believe what my father – a school principal and teacher – was telling me. I came back that first semester [January 1947], and I think I made all As. I wanted to prove to myself that I could do it.

his absence from the College’s yearbooks: I was busy. When ships came into Charleston Harbor, there was a pool of relief officers, and, as a licensed merchant marine officer, I would go down there at night. I would come aboard and take charge and be the officer on the deck. They paid me pretty well for doing it. Without that, I couldn’t have made it through the College. I got along well until they started shutting down all of the electricity on the ship. I went to the Sears Roebuck on the corner of Calhoun and King and bought a gasoline lantern. I would pump it up and study by the light of that lantern. It was a wonderful job – I could study where no one would disturb me and I got paid for it. I owe a lot to those merchant ships in this harbor.

on saving the life of a fellow alumnus: It was around 1945. It was in the winter time. There was ice floating down the East River [New York]. And I got on a sea taxi, which would take seamen out to the various ships anchored out in the harbor. And this one night, I was on the sea taxi, and these other fellows were going to a different ship. This one man grabbed a gang plank and slipped – it was icy – and fell overboard. I didn’t know who he was. I reached down and grabbed the collar of his pea coat and hollered for some other fellows to help me. Back on the boat of the sea taxi, I look down and here’s Charlie [Charles Foster ’50]. It was funny – it was my old friend, Charlie! [This story has grown in the retelling by Edwards’ lunch crowd, who like to think that Edwards singlehandedly pulled Foster out of the water by just Foster’s hair.]

Balancing politics with his private oral surgery practice in Charleston: Remember, I’m different from a lawyer. I can’t have a clerk working in the courthouse making me money while I’m gone. I was an oral surgeon – when my fingers quit working, then my income stopped. It was very stressful. I was torn between my allegiance to my patients that I had cut on that morning and the Senate. I worked it out, fortunately, but it took a lot out of me. I was working 24 hours a day.

his route to President Reagan’s cabinet: The first day in the S.C. Senate, Tommy Hartnett [another Republican senator who had been elected with him in 1972] and I went up to the Senate door and it was locked. We knocked and the sergeant at arms told us, “Sorry, we’re having a special session. This is the Democrat Caucus and they’re dividing the appointments for the various committees.” So, we didn’t get into the room until they were done. They assigned me to the Nuclear Commission because no one wanted to be on it. I became a strong supporter of nuclear energy.

And that paved the way for me to become Reagan’s secretary of energy. Reagan asked me to renew the nuclear option and that is what I spent my time in Washington trying to do. [During his tenure, Edwards’ office wrote and got passed the Nuclear Energy Act of 1982 as well as worked to deregulate the oil industry.]

his legacy as president of MUSC: The Medical University was probably my most delightful years. It is always fun to build, and we had some terrific successes there. I think the university is well on its way to taking its place among the leading academic medical centers in the country. I am proud of what we did, the foundation we laid and the building that we did there.

advice for today’s college student: First thing, decide what you want to do, and that’s a tough decision to make. And I think we need to improve our method of advising young people what fields they are fitted for. I’m sure there are a lot of tests that I don’t know about today that test what they are strong in, but first you got to decide what you want to do with your life. So, get a good foundation in fundamentals, like basic science. Work hard, study and decide what you want to do and stick with it.