Nearly 20 years after College of Charleston alumnus Jonathan Geisler ’95 took Geology Professor James Carew’s paleobiology class, the two are working together again. Geisler and Carew have made a tremendous evolutionary discovery based on the fossil of a previously unknown whale species found in the Charleston area.

Alumnus Mark Havenstein of Lowcountry Geologic and another local fossil collector initially found the fossil, which was later sold to fossil-collector Mace Brown. Brown prepared the fossil himself and invited Carew and Geisler to come see it years before he donated his fossil collection to the College in 2013.

[RELATED: Find out more about the new species of whale]

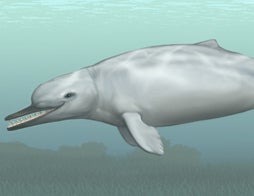

Carew and Geisler officially named it Cotylocara macei (C. Macei), the genus Cotyocara means “cavity head” and refers to unusual depressions in the skull that are unique to this species. The species name recognizes Mace Brown’s donation of this and other specimens to the College of Charleston.

Geisler, now an Associate Professor of Anatomy at New York Institute of Technology, said he knew the first time he saw the fossil that he was looking at something unusual. He traveled to Charleston several times to work closely with Carew to identify the creature’s unique anatomical features. He is the lead author of a research paper on this new whale species to be published in the prestigious scientific journal Nature on March 12, 2014.

[RELATED: Check out Nature]

“Having our findings published in Nature is very exciting – this is one of the top journals of science in the world,” Geisler said. “It signals that our findings are of broad interest to the scientific community and anyone interested in evolution, not just specialists in our field.”

While the discovery of C. macei alone is thrilling for the scientific and Charleston communities, the key discovery are characteristics in the creature’s skull that led Geisler and Carew to believe it clearly indicates toothed whales’ ability to echolocate further back in whale phylogeny (the “family tree”) than was previously documented.

“The skull of this creature has significant sinuses and other features, such as skull asymmetry and telescoping that most likely allowed it to echolocate,” Carew said. “The question, scientifically, has been, ‘When did the ability for whales to echolocate arise,’ and this roughly 28-million-year-old whale has numerous features in the skull that suggest it had the capability of echolocation.”

With help from colleagues at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC), specifically T. Holden, and co-author Matthew Colbert of the University of Texas at Austin, Geisler and Carew had the C. macei fossil CT-Scanned and then digitized as a 3-D model. Using both the fossil and the 3-D model, the team gathered additional evidence to support their conclusion that the cavities were used to facilitate echolocation.

[RELATED: Learn more about the Mace Brown Museum of Natural History]

“Toothed whales echolocate in a unique way,” Carew said. “They have a constriction in the nasal passage just beneath the blowhole that acts as lips, called phonic lips. They push air through the phonic lips to create high-frequency vocalizations, sort of like letting air out of a balloon, and then use air sinuses and a fat-filled body called the melon to control the sound. In order to do that underwater they need a reserve of air, so these sinuses were cavities full of air that permitted the whale to echolocate repeatedly while submerged.”

The C. macei fossil is on display at the Mace Brown Museum of Natural History, along with many additional whale fossils recovered in the Charleston area.

For more information, contact James Carew at [email protected].