Don’t get him started. But if you do, ask Jim Newhard what makes Charleston so special for archaeological students, be prepared for a long laundry list of answers:

Charleston is the site of some of the earliest European colonization of the New World. It enjoys the influence of the Caribbean. Its slave trade figures within the African Diaspora. It’s home to well-preserved examples of the plantation system. It has historical sites associated with the Revolutionary War. The Civil War started in Charleston. Not to mention its role in Reconstruction. And then there’s the fact that, within a two-hour drive, you can find evidence of some of the earliest human settlers in North America. And, of course, there are the marine archaeology opportunities available in local waterways and the Atlantic Ocean. He could go on.

With so many local opportunities to learn about and examine what remains from the past, it only makes sense for the College to offer its students the chance to major in archaeology.

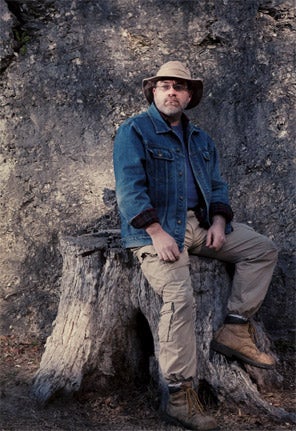

“We’re in Charleston, for God’s sake. This is the most amazing archaeological environment on the continent,” says Newhard, associate professor of Classics, adding that – beyond having proximity to a wealth of local historic sites – the College has a diverse faculty with expertise and research interests that extend far beyond the Lowcountry. “It’s not just the uniqueness of where we sit: The faculty has a worldwide reach to themselves.”

And so, it was a no-brainer when, in 2006, the College began offering its students a minor in archaeology, making it the only South Carolina school to do so. And now it’s the only state institution to offer an archeology major, too – and it’s graduating its first class of archaeology majors this spring.

Among the inaugural class is senior Jeremy Miller, whose studies at the College led him to the Roman military camp ruins in modern-day Romania. Working with Alvaro Ibarra, assistant professor of art history, Miller has studied aerial and satellite imagery of the ruins of five camps in the Olt River Valley of Transylvania and in January helped present their findings to the Archaeological Institute of America. Miller’s analysis – which was aided by his six years of experience as a U.S. Army squad leader of combat infantry in Afghanistan – included an assessment of the military effectiveness of each camp.

Closer to home, Miller worked last summer in Aiken County, S.C., where he and fellow archaeology enthusiast Nate Fulmer ’12 excavated a 1950s concrete bomb shelter, allegedly built by a nuclear engineer who’d been employed at the Savannah River Site. Their film of this work, Helter Shelter: A Backyard Time Capsule in the Shadow of the Bomb Plant, can be seen on YouTube. After graduation, Miller plans to pursue a master’s degree, likely specializing in landscape or warfare archaeology.

Senior archaeology major Jessie Rabun plans to continue her education, too, though she counts on using her archaeological training to inform an advanced degree in Classics. Rabun, a triple-major who is also majoring in history and Classics, spent some of her time as an undergraduate volunteering at the College’s Dixie Plantation, where she helped look for the foundations of a slave settlement. She took her digs abroad the summer after her sophomore year, venturing to Greece, where she worked on an outdoor shrine at a Mycenaean site in Pylos in the Peloponnesian region. Among other artifacts, Rabun and her crew found remnants of pottery, drinking cups, figurines and the bones of animals thought to have been used as sacrifices.

Despite the varied locales and diversity of artifacts found in them, Rabun says that all archaeological digs have at least two things in common: First, you’re going to learn a lot of things very quickly; second, you will form close, long-lasting bonds with your colleagues and fellow students. Waking up to start work together at 6 a.m., six days a week, will do that to you.

“It’s a really great journey,” Rabun says of her experiences in archaeology.

Rabun and Miller, among 28 archaeology majors, are slated to graduate this spring. Both of them, says Newhard, will have a leg up on his or her competition from other institutions, being better prepared for advanced study or immediate careers in archaeology– whether with the government, a consultancy or the field of cultural resource management.

What’s exciting, too, is that this crop of archaeology majors is just the beginning, and that from now on students at the College can fully capitalize on the archaeological opportunities available in their own backyard.

“We are morally bound by our place to have an outstanding program in archaeology,” says Newhard. “You can’t put a shovel in this place without kicking stuff up.”

And – considering the impressive inaugural class of archaeology majors – the College has kicked up something pretty great. Eureka!