What are the defining characteristics of a preeminent teacher-scholar? For one professor of anthropology, the answer is quite simple: an insatiable curiosity for life and a desire to pursue its fleeting satisfaction without fear, without hesitation and without end.

story by Mark Berry

photography by Peter Frank Edwards ’93

A young man stares intently at the floor of his cell. A sliver of daylight illuminates a meandering thin black line that runs from his cell’s ground-level window to this spot on the floor.

It’s the 1960s in East Africa, and the prisoner is John Rashford, a Quaker student circling the globe as he studies human culture.

His trip to study Swahili in Tanzania has hit a bit of a road bump. After a 30-hour trip from Nairobi to Dar es Salaam on a crammed and uncomfortable bus, Rashford wakes up with his money and proper documentation stolen and is promptly dropped off with the local authorities.

Not only the victim of a robbery, Rashford is a victim of bad timing. He has arrived in Tanzania right on the heels of Stokely Carmichael, the Black Panther advocate who had recently criticized the country’s government and society in general. It’s not exactly a good time to be seen as an “American,” especially without means and a passport.

“There’s a proverb in my home country,” Rashford says in his rhythmic Jamaican voice. “If you can’t catch Quaco, catch him shirt. I am the shirt, you understand.”

His detention occurs on a Thursday, Thanksgiving to be precise, and the U.S. embassy is closed for the long weekend. So, Rashford, penniless and without contacts, spends his days alone in jail studying the movement and cooperation of ants as they haul off minute pieces of grizzle from the meat of his meals.

There’s nothing else to do. The police had taken everything – his guitar, his books, his writing materials – so the ants serve both as his companions and his subjects of study. “I found those ants infinitely interesting,” Rashford recalls with a smile.

And that’s John Rashford for you: consummate student, curious observer – no matter the circumstance, whether a college library or a Tanzanian jail cell.

Blossoms of the Mind

In a Charleston single house located on St. Philip Street, you can find John Rashford’s office. Walking up the creaky steps to the second floor, you enter a doorway on the right, into a two-room suite. The outer room is stacked with the staples of academia – mounds of scholastic journals, papers, magazines and books, punctuated by several varieties of green, leafy plants and a few scattered boxes of Miracle-Gro, some empty, some full.

In the inner room, where his desk is engulfed in more papers and more plants, you get a snapshot of John Rashford the scholar. Books are like kudzu in this part of his office. They overtake you. They tower over you. They envelop you. His shelves are overstuffed, sometimes two or three books deep, with titles like Fantastic Trees and Supernatural as Natural: A Biocultural Approach to Religion packed tightly against The Wealth of Nations, Fatal Harvest: The Tragedy of Industrial Agriculture, Uganda poet Okot p’Bitek’s Song of Lawino and numerous tomes on Hegel’s philosophy. Paintings and prints of the baobob tree– all gifts from former students – hang on his walls. The gourd-like fruit of the baobob (which look more like maracas than food) rest randomly on his bookshelves. The branches and leaves of a Japanese red pine fall like dreadlocks off his desk – what he calls “Jamaica-style Bonzai.” Piles of papers, photos and other materials obscure a Yamaha keyboard, bongo drums, record albums, a microphone and amplifier. In the corner, almost hidden between two bookshelves, a sleeping bag serves as a makeshift case for his sitar.

A casual observer might rightly be confused in this academic den and come up with several conclusions about the nature and interests of this scholar: Obviously, he’s a musician. No, a philosopher. Perhaps a botanist or biologist. Maybe, a poet. Of course, a historian.

But John Rashford is, first and foremost, an anthropologist.

“My travels early on opened me up to anthropology,” explains Rashford, who as a college student at Friends World College trekked around the world, with stops in Mexico, Sweden, Austria, Kenya, Ethiopia, India, Thailand, Hong Kong and Japan, to name but a few. “Seeing how so many different people, so many different cultures respond to their geography, their times and to each other … that got me interested in understanding the bigger picture of human evolution.”

For Rashford, that “bigger picture” centers on the environment in which people live, and that means recognizing plant life.

“Understanding the human-plant relationship is a critical prerequisite,” Rashford says, “for understanding human evolutionary history, whether it’s medicine, the origins of agriculture, religion or the rise of the industrial world. Plants are fundamental for understanding what it means to be a human being. If you look at the Western religious tradition, the fate of human beings is determined by our relationship to trees.”

Rashford’s interests in flora did not start from an academic viewpoint, but from his cultural background. As a boy coming of age in the 1950s in Port Antonio and later Kingston, Jamaica, Rashford and his friends would gather wild fruits, such as tropical almonds, tamarinds, cucumbers and passion fruit, in the woods close to home. “My family always grew things in our garden,” he adds. “Growing stuff and collecting stuff were important to us all.”

So that inherent interest in plant life and its relationship with humanity informed his research in the area of ethnobotany – which some scholars identify as “the science of survival.” Rashford’s doctoral dissertation explored the practice of intercropping in Jamaica. He is widely regarded as the expert on the dispersal and cultural importance of the baobob tree in the Americas. He has written the seminal paper on the ackee fruit’s cultural significance to Jamaica and has done considerable research on the sacredness of fig trees in human tradition.

But his many academic accomplishments may pale in comparison to his past four years of service and leadership. He serves as one of three scientific advisers to the National Tropical Botanical Garden. He is the president of the Charleston Museum’s Board of Trustees. He sits on the Board of Directors for the Gaylord & Dorothy Donnelly Foundation, a dual-mission nonprofit dedicated to land conservation and the arts in the Lowcountry and Chicago.

After a long tenure on the board of the Coastal Conservation League, he also worked on the Trust for Public Land’s S.C. Advisory Council. And he served a three-year commitment as the president of the Society for Economic Botany, the premier scientific society for research on the interrelationships between people and plants. He also had the honor of coordinating and hosting the society’s 50th anniversary this past summer, which included the organization of a symposium on African ethnobotany in the Americas.

“I knew that if I didn’t do it now, I wouldn’t do it,” Rashford says of his service. “You might call this the flowering of my career.”

Needless to say, no moss has gathered on this rolling stone of a scholar. And the top researchers in his discipline recognize just that.

“Some people may have visited more places around the globe,” says Bradley Bennett, a professor of biological sciences and director of Florida International University’s Center for Ethnobiology and Natural Products, “but I doubt that there are very many who have immersed themselves in so many different cultures. John is a broadly trained scholar with diverse interests. Though trained as an anthropologist, he knows more plant taxonomy than many botanists.”

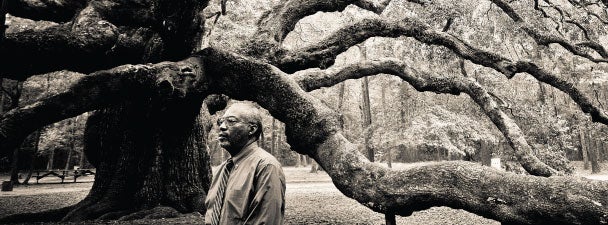

Rashford’s expertise is not lost on Will McClatchey, professor of botany at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. “John is a lover of trees,” McClatchey observes. “He knows they are critical to the survival of not only the earth, as its very lungs, but that so many of earth’s cultures have invested their souls within the bowels of trees, and that trees are also critical to the survival of cultural diversity. He has championed several sorts of trees and the cultures that elect to share intertwined lives with them. In this way, he has become intertwined with trees himself, probably as all people should.”

Perhaps more importantly, “John is a leader who inspires other scientists,” McClatchey continues. “He motivates through his willingness to commingle biology, art, social inquiry and the joy of exploration.”

James Miller, dean and vice president for science at the New York Botanical Garden, agrees: “His ability as a keen observer of human behavior and culture and his understanding of how people interact with plants and other natural resources, coupled with the clarity in his writings, help him teach the rest of us great things about why plants are so important in our day-to-day lives and why he is so respected as a leader by his peers in the field.”

Planting Passion

The last student hurries into the full classroom of ANTH 362: Social and Cultural Change. She turns sideways, trying not to hit the other students with her book-heavy backpack as she shuffles to the back of the room, stepping delicately over coffee mugs and plastic soft drink bottles. She finds a seat and thumbs her cell phone to mute it. John Rashford stands at the front of the class going over the roll. She hears her name, responds with a breathless “here,” and receives an understanding “OK” and a sincere smile.

Rashford turns and draws a long blue line across the white board and bookends it with “5–8 million years” and “present.”

Today’s discussion is about Marx and Engels’ The Communist Manifesto, and its role in changing society. But that classic work is not the centerpiece of that day’s lecture. Far from it.

“Sharing is the cement … the glue of social evolution,” he tells the class. “The great apes don’t share food. Only humans share. Exchange is the heart of human life.”

Rashford then spends the next hour talking with his students about the different types of human exchange, moving seamlessly up and down the blue timeline on the whiteboard, as well as interjecting short lessons on horticulture, philosophy, history, ethics and genetic engineering.

When one student fumbles over his thoughts regarding the universality of social hierarchy and attempts to abandon his answer, feeling the pressure and eyes of the 29 other students, Rashford smiles and prods him, “Don’t give up the delight of scholarship. We are here to speculate.”

There is a calmness and gentleness to John Rashford, like a warm Caribbean breeze. The student relaxes and does just that – he speculates.

That speculation is critical in Rashford’s mind because it gets to the core purpose of the liberal arts and sciences experience: Students must recognize that all living things are connected and all disciplines are connected. “I truly believe that a liberal arts education is a prerequisite for a life well spent,” Rashford says. “And by better understanding the world and life – that it’s more than a good job, a good living, a good income – it will help you enjoy the life you live and will help you live the life that is meaningful to you.”

Since his arrival at the College in 1983, a John Rashford class, for many students, is a before-and-after event in their life. It’s a class you dare not hit the snooze button on or skip it for the beach. It marks an evolutionary step in your intellectual development.

Perhaps the greatest praise any professor can receive comes from Lucas Moriera ’09: “I can honestly say that he was the most important part of my education, at the College or otherwise. It’s not an exaggeration when I say that I majored in John Rashford.”

While Rashford may have a long way to go in becoming a recognized major, his contributions to his students are abundant.

Just ask Amanda Watson Smith ’90: “Professors like Dr. Rashford helped me see that many of the ‘norms’ and expectations we have are just societal constructs that are different elsewhere. What an eye opener for a traditional Southern girl! He taught me that people approach things differently because of the society they are from. Remembering that helps me understand people better, and that has helped me at work, in graduate school and in my faith life.”

Phillis Kalisky Mair ’93 was one of the students who was sure to get to class early and find a good seat. “I would have to sit up front because of his soft voice,” she remembers. “Once there I realized I had a front-row seat to higher education.”

For Allison Cleveland ’98, he was a perfect combination of kindness, enthusiasm and thoughtfulness. “Most of us sat spellbound when he lectured,” she recalls. “He didn’t just lecture about concepts – he combined those concepts with real-life examples, making his classroom lectures relevant to the real world. He encouraged travel and exploration and appreciation for other cultures. I thought of him often as I worked on my Ph.D. in psychology at the Max Planck Institute in Germany.”

Rashford simply shrugs when he hears such praise, more out of modesty than indifference. “I think my students respond to my enthusiasm of the subject, my curiosity. Because what I am teaching is what I am working on myself,” Rashford explains. “My motivation has never been to be a great teacher or eminent scholar. I have simply been satisfying my own curiosity.”

As his mind turns to retirement in the next few years, Rashford sounds nothing like a future retiree. Rather, he sounds like a man on a mission to contribute even more. “There are several projects I would like to finish and write about,” Rashford says. “Like this idea of anthropology and time, the importance of the notion of the tree of life and human culture, human beings and plant dispersal and mimicry in nature. These are just a few things that I have worked on for a long time, and I think I can contribute something to the general literature.”

“But you know,” he adds, a large smile spreading across his face, “learning never ends. Something else might just interest me.”

And knowing John Rashford and his relentless curiosity, the best may be yet to come.