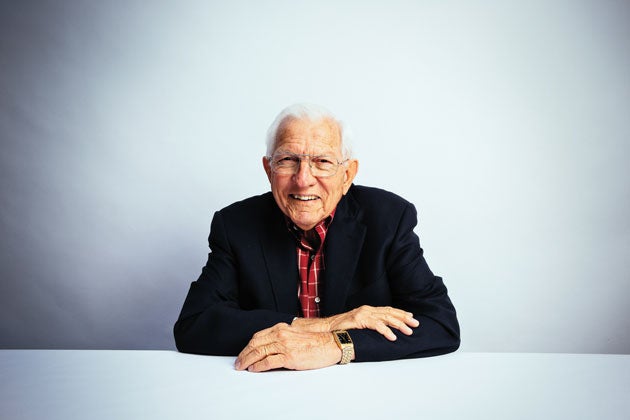

When former Governor Jim Edwards ‘50 passed away on December 26, 2014, the College said goodbye to one of its most accomplished alumni. Among fellow Cougars, perhaps only John C. Frémont, who explored the West, served as governor of both Arizona and California, was a U.S. Senator and also the Republican Party’s first presidential candidate, can hold a candle to Edwards’ record of public service.

A veteran of World War II (and later the Korean War, too), Edwards graduated from the College and continued his education in dentistry. After opening an oral surgeon practice in 1960, Edwards became involved in local politics, first winning election to the South Carolina Senate in 1972. Two years later he was voted into the South Carolina Governor’s Mansion, the first Republican governor in the Palmetto State since Reconstruction.

A veteran of World War II (and later the Korean War, too), Edwards graduated from the College and continued his education in dentistry. After opening an oral surgeon practice in 1960, Edwards became involved in local politics, first winning election to the South Carolina Senate in 1972. Two years later he was voted into the South Carolina Governor’s Mansion, the first Republican governor in the Palmetto State since Reconstruction.

In 1981 President Ronald Regan called on Edwards to become U.S secretary of energy. Almost two years later, Edwards became the president of the Medical University of South Carolina, helping modernize the medical campus over an impressive tenure of 17 years.

In 2013 the College of Charleston Magazine caught up with Edwards and asked him to reflect on his life, including his decision as a young man to temporarily drop out of the College during wartime to join the U.S. Maritime Service. His remarks follow:

On dropping out of the College before taking a single class: When you’re 17, you don’t have very good judgment. I busted out of the College and went to sea. I started off as a messman – the dishwasher on a troop ship. It can’t get much lower than that. I then became an ordinary seaman and worked my way up.

One of the things I did, I was on a hospital ship. When I was off watch duty, I would go down into the medical ward and visit the wounded. As merchant seamen, we took the troops to the beach and left them. They did the rest. Seeing the results of war had a profound effect on my life.

I was fortunate enough to get on board the USAT George Washington. I expressed interest in learning navigation, rules of the road and seamanship. I got promoted to acting junior third mate, and I was on the bridge, with all the books and instruments, and the senior men taught me. I studied for 18 months and then took a long, arduous exam in New York. I passed it and got my license – an unlimited license, which is the best you could get. I was very proud of it. That was my first real accomplishment. I brought my license home in December 1946 and hung it on the Christmas tree for my mother and father.

On coming back to the College: When I told my father that I was going to come back to the College and get my degree, he said, “You’re just wasting your time. You shouldn’t do that. You’ve been successful at sea, so you ought to stay at sea.” It made me so mad. I couldn’t believe what my father – a school principal and teacher – was telling me. I came back that first semester [January 1947], and I think I made all As. I wanted to prove to myself that I could do it.

On his absence from the College’s yearbooks: I was busy. When ships came into Charleston Harbor, there was a pool of relief officers, and, as a licensed merchant marine officer, I would go down there at night. I would come aboard and take charge and be the officer on the deck. They paid me pretty well for doing it. Without that, I couldn’t have made it through the College. I got along well until they started shutting down all of the electricity on the ship. I went to the Sears Roebuck on the corner of Calhoun and King and bought a gasoline lantern. I would pump it up and study by the light of that lantern. It was a wonderful job – I could study where no one would disturb me and I got paid for it. I owe a lot to those merchant ships in this harbor.

On saving the life of a fellow alumnus: It was around 1945. It was in the winter time. There was ice floating down the East River [New York]. And I got on a sea taxi, which would take seamen out to the various ships anchored out in the harbor. And this one night, I was on the sea taxi, and these other fellows were going to a different ship. This one man grabbed a gang plank and slipped – it was icy – and fell overboard. I didn’t know who he was. I reached down and grabbed the collar of his pea coat and hollered for some other fellows to help me. Back on the boat of the sea taxi, I look down and here’s Charlie [Charles Foster ’50]. It was funny – it was my old friend, Charlie! [This story has grown in the retelling by Edwards’ lunch crowd, who like to think that Edwards singlehandedly pulled Foster out of the water by just Foster’s hair.]

On balancing politics with his private oral surgery practice in Charleston: Remember, I’m different from a lawyer. I can’t have a clerk working in the courthouse making me money while I’m gone. I was an oral surgeon – when my fingers quit working, then my income stopped. It was very stressful. I was torn between my allegiance to my patients that I had cut on that morning and the Senate. I worked it out, fortunately, but it took a lot out of me. I was working 24 hours a day.

On his route to President Reagan’s cabinet: The first day in the S.C. Senate, Tommy Hartnett [another Republican senator who had been elected with him in 1972] and I went up to the Senate door and it was locked. We knocked and the sergeant at arms told us, “Sorry, we’re having a special session. This is the Democrat Caucus and they’re dividing the appointments for the various committees.” So, we didn’t get into the room until they were done. They assigned me to the Nuclear Commission because no one wanted to be on it. I became a strong supporter of nuclear energy.

And that paved the way for me to become Reagan’s secretary of energy. Reagan asked me to renew the nuclear option and that is what I spent my time in Washington trying to do. [During his tenure, Edwards’ office wrote and got passed the Nuclear Energy Act of 1982 as well as worked to deregulate the oil industry.]

On his legacy as president of MUSC: The Medical University was probably my most delightful years. It is always fun to build, and we had some terrific successes there. I think the university is well on its way to taking its place among the leading academic medical centers in the country. I am proud of what we did, the foundation we laid and the building that we did there.

On advice for today’s college student: First thing, decide what you want to do, and that’s a tough decision to make. And I think we need to improve our method of advising young people what fields they are fitted for. I’m sure there are a lot of tests that I don’t know about today that test what they are strong in, but first you got to decide what you want to do with your life. So, get a good foundation in fundamentals, like basic science. Work hard, study and decide what you want to do and stick with it.

RELATED: Edwards was not the only mover and shaker to graduate from the College in the 1950s. Read about the “Old Maroons” – a handful of Edwards’ classmates who have maintained an informal Cougar social club for years.