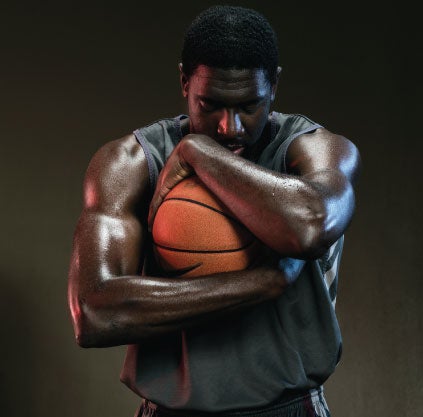

For the past four seasons, senior co-captain Adjehi Baru has been a mainstay for the Cougars. In probably the toughest season in the program’s history, Baru reminds us what it means to never give up, to never stop fighting. And, in his relentless play and his unwavering will to compete, the star recruit from the Ivory Coast will be forever remembered – and celebrated – for his example in the maroon and white.

by Mark Berry

photography by James Quantz

It’s sanctuary quiet. All seem frozen, deep in concentration, locked in an internal conversation best not disturbed. Perhaps over there, someone’s leg nervously jiggles or maybe someone else shifts his weight a little, but all is done without sound. For the most part, it’s a tableau of gangly statues adorned in white jerseys, broad-shouldered figures crammed into four rows of folding chairs in front of a white board in the middle of the men’s basketball locker room.

From behind, they might remind you of fighter pilots waiting for a war-room briefing. A battle, an aerial dogfight of sorts, is only a few minutes away. The seconds on the digital clock, hanging at eye level to their left, soundlessly tick backwards. The coaches, in an adjacent room, are making the final adjustments to the game plan against Delaware, last season’s Colonial Athletic Association champions.

For now, it’s just the players. The silence is temporary. It always is. Sounds begin to seep in, finding whatever seams and cracks there are between TD Arena’s locker room and the stands above. A familiar bass line, separated from its melody, thumps on the arena’s PA system, but, in here, it is only a distant heartbeat. It’s comforting in a way, something akin to the warm security of the womb. But that feeling vanishes with the short blasts of the pep band’s trumpets and the crash of cymbals, acting like faraway flashes of lightning in the mind’s eye.

Now, there is a soft shushing sound in the back of the room. Shh, shh, shh. It’s impossible not to feel its rhythm. To feel the circular motion of Adjehi Baru as he pedals on a lone stationary bike. Shh, shh, shh. It might even be soothing, like the sound of an early-morning rain, except that the clock is counting down, a flashing reminder of the work at hand.

Then the coaches enter. The sibilance is replaced by staccato clapping, the coaches yelling, “Here we go, here we go.” Suddenly, a pent-up energy is released in the room. All the players are clapping, nodding, smiling: The statues’ faces come to life. Everyone’s that is, but Baru’s, a white Powerade towel draped on his head like a warrior’s hood. He is pedaling, pedaling, pedaling. His face seems carved in obsidian: expressionless, yet full of emotion.

Then the coaches enter. The sibilance is replaced by staccato clapping, the coaches yelling, “Here we go, here we go.” Suddenly, a pent-up energy is released in the room. All the players are clapping, nodding, smiling: The statues’ faces come to life. Everyone’s that is, but Baru’s, a white Powerade towel draped on his head like a warrior’s hood. He is pedaling, pedaling, pedaling. His face seems carved in obsidian: expressionless, yet full of emotion.

First-year head coach Earl Grant stands before the white board and runs through the game plan, 10 tactics to end the Cougars’ current seven-game losing streak. It’s rapid-fire instruction: “limit the transition,” “no refusal,” “bother the passer,” “emergency switch,” “flood the paint,” “deny, wall up and stay down,” “four Texas,” “shot fake,” “stick backs,” “inside out, no doubt.”

Grant then takes a deep breath and looks across the room. “I told you about the treasure,” he says. “Everybody’s got a treasure inside them. Everybody in this room has got something special about them. It might be to take a charge or get to a loose ball. Yours might be to have the most assists. Yours might be offensive rebounds. Yours might be to block a couple of shots. Yours might be to protect the rim. At the end of this game, we got to be sure that we can tell what your treasure was. Whatever it is, you do the best you can do with it, and we’re going to find a way to win. Let’s go, baby! Let’s go, baby!”

The players rise, some hop, some clap, some high-five one another. Baru leaves last. Slow. Silent. Focused.

The locker room is quiet for 20 basketball minutes. Then the door swings open and the players file back in. The Cougars are down by four points at the half.

One or two players go to the adjoining bathroom. Some, soaked in sweat, slouch into their chairs and drain entire water bottles. Baru again mounts the stationary bike and stays in motion: an attempt to keep his surgically repaired right knee from tightening up.

“Good job, team,” says Baru, his voice a deep bass with a soft French lilt. “We got to do this as a group. We got to talk to each other. Communicate.”

Heads nod in agreement. His voice seems to linger in the air, as if hovering near the four inspirational words etched on the white signs hanging above their lockers: Character, Passing, Trust and Toughness. Then, it’s quiet again, except for the shh, shh, shh sounds of Baru’s bike.

“We go all out tonight, guys,” says Baru, the intensity rising in his words. “All out. All out.”

Come and Take Them

Come and Take Them

What is a champion? Basically, we would all agree that a champion is a winner. In basketball, it’s the last team standing, the players and coaches hoisting a trophy above their heads in a shower of confetti, pointing a single index finger in the air and ascending a step stool to cut down the strings from the rim. For most, that is the picture of success.

And the College knows that version, has lived that version. Over the years, the Cougars have won a national championship, secured titles in numerous conferences, toppled giants in remarkable upsets and had their name called on Selection Sunday during March Madness.

But none of those things happened this year. In fact, that kind of success has been eluding the College for more than a decade. Sure, there have been great games, moments on the periphery of a breakthrough, but the extraordinary and sustained success under legendary head coach John Kresse has not been duplicated since his retirement in 2002.

If anything, this will go down as yet another year of disappointment, another season where the Cougars didn’t live up to their potential and failed to stay relevant in the national basketball conversation. In the category of wins and losses, this will be remembered as one of the worst – if not the worst – season in the College’s history.

That negative view, of course, would be a mistake. The team’s effort, game after game, in this seemingly lost season is nothing less than heroic. Like no other team in the nation, these Cougars kept fighting in the face of incredible adversity: four coaches in four years, a switch to a more prestigious and more competitive basketball conference, a summer of discontent played out in the national media and the tragic and unexpected death of former teammate Chad Cooke over the winter break. Even Job would be sympathetic to these Cougars.

Perhaps a little history lesson might put things in perspective. Ancient history, that is. The Battle of Thermopylae, for example, was a victory for the Persian empire: a military footnote in history when, yet again, a superior force crushed a much smaller one. But, in time, the Spartans’ valiant last stand proved a turning point for Greece – a defeat that inspired and unified the country.

In many ways, the 300 Spartans who fought so desperately in that loss have a lot in common with the 15 men who make up the Cougars this season. Like those outnumbered soldiers, these student-athletes never gave up, even when things might have looked hopeless. They struggled on, doing everything they could – all the little things in practice, the in-depth film study, the extra individual workouts. In so many games this season, victory just slipped out of their grasp, with most losses by just a maddening few points or even a single possession. Rarely, if ever, did you see these Cougars hang their heads. If anything, each loss pushed them to fight harder. But some falls – no matter the effort, no matter the will to change it – those falls cannot be stopped.

In that respect, we need to change our calculus in measuring this team. Statistics pass cold-blooded judgment on a game that demands so much of the heart. And in that light, we may view these players, led by senior co-captain Adjehi Baru, for what they really are: champions of spirit.

Strong Inside

Strong Inside

How tough can you be when adversity, like a heavyweight boxer, keeps knocking you down?

Adjehi Baru knows something of struggle. Not much has been easy for him. Each step on his path to right here, right now has been rocky, uphill, strewn with figurative thorn and bramble.

His difficult journey began as a child growing up in the Ivory Coast. His earliest memories, however, are pleasant: a young boy devoted to his parents, each night stealing into their bed and the comfort of their warm embrace. His father, a celebrated deputy mayor of Tabou, was later a delegate in the national government’s legislature in Abidjan, where Adjehi grew up. But like all politicians, he had enemies. When Adjehi was 6 years old, his father passed away during exploratory surgery of his kidneys, which his family believes was the result of poisoning. Baru remembers as a child being constantly warned by his mother to eat nothing that was not prepared by her hands. Each time he would return home from a friend’s house, she would pepper him with questions on whether he ate anything there.

As might be expected, after his father’s apparent assassination, Baru became dependent on his mother. Over the next few years, he retreated into himself, lacked discipline and had problems at school. His mother decided to send him to a family friend, who was the captain of a military base in Daoukro, about three hours from the city.

“I was a mama’s boy,” Baru observes. “She moved me to change me. I went to school there, and the place was good. It made me tougher. You learn a lot when you are away from the people that you love the most.”

After a few years at this high-walled fortification, Baru returned to civilian life in Abidjan. But soon, all hell broke loose across the country as rebels clashed with pro-government forces. It was a chaotic and dangerous time. Fighting was particularly intense in Abidjan, but for a boy like Baru, war’s ravages weren’t always so terrifying.

“In the mornings, my friends and I would go walking around,” he recalls of those days marked by machine gun fire, mortar blasts and curfews. “We just looked at it. We didn’t see any shooting, but everything was broken; people were stealing. Yes, you had to be really careful on where you were going. I knew people who went down the wrong street at the wrong time. A couple of those guys, you just knew that something was going to happen to them at the end.”

But war did not define his world. Hardly. The great change maker in Baru’s life was basketball, which he started playing seriously at age 13. While he’d had a basketball court in his Hibiscus neighborhood compound and had played with friends, soccer was the main sport, basketball a distant second. But as he got older, the game took hold of him.

“I loved every part of it,” Baru says, his eyes lighting up. “I especially love defense: stopping the other team from scoring, frustrating them. I love getting in their heads.”

In just a few years, he would get into the heads of a lot of people. His natural talent and size were obvious to scouts, and the International Basketball Federation coordinated his placement at a school in Miami, where the 16-year-old could fine-tune his game and improve his educational standing as well.

If Charles Dickens had been a West African, he might have penned this story of Baru’s journey to America. The high school in which Baru enrolled, with two fellow Ivory Coast athletes, turned out to be a sham, a cross between Bleak House and Oliver Twist. Ostensibly running a private school for poor children, the Fagin-like principal (who was also the basketball coach) was taking advantage of an apparent loophole in Florida education funding and was using those state resources to build a high school powerhouse of international talent. Baru lived in a house in Opa-locka with the other foreign players without any adult supervision (which was against state law), and his “school” was a converted homeless shelter that was more gymnasium than classroom.

“I knew this wasn’t normal,” Baru recalls. “I just had a feeling. But I did not want to complain. Then, one day, a person with the team picked us up at the house and said we needed to do some ‘fundraising.’ We went to the street with a bucket. I didn’t do it. The second time, someone came to me with the bucket and said, ‘if you are not going to do it, then you are not going to have something to eat.”

Baru again refused to beg for his food, and soon after, left the school, moving to the D.C. area, a hotbed of basketball talent, under the direction of his uncle, who lives in France. But one bad situation was only replaced by another.

Imagine this: a teenager who barely speaks the language in a foreign country trying to navigate a complicated landscape of education and athletics, where everyone seems to be playing an angle. Baru lived with a foster family in Washington, D.C., and again struggled to find his footing due to the language barrier. However, Amateur Athletic Union basketball coaches had no problem finding a place for him on their teams.

Fortunately, fate soon provided a ray of hope. Pat Branin, who competed against Baru in the AAU circuit and saw him frequently at basketball camps, formed a friendship. They talked sports and music, and Branin learned of Baru’s tough situation. Branin’s family, with the help of Baru’s uncle, worked out an arrangement that allowed Baru to live with them and attend school with Pat in Richmond, Va.

And the story here turns magical, almost begging for Hollywood to make it: Baru helps Branin lead their high school team to two very successful seasons. Baru becomes the top basketball prospect in Virginia and the third highest–rated big man by ESPN College Basketball Ranking. Schools such as Maryland, North Carolina and Virginia Tech actively recruit him (even Kentucky comes calling), but Baru drops in unexpectedly at the College and falls in love with a city that reminds him of his African home. The college sports world gushes over such storylines, and they should: They are rare.

And the story here turns magical, almost begging for Hollywood to make it: Baru helps Branin lead their high school team to two very successful seasons. Baru becomes the top basketball prospect in Virginia and the third highest–rated big man by ESPN College Basketball Ranking. Schools such as Maryland, North Carolina and Virginia Tech actively recruit him (even Kentucky comes calling), but Baru drops in unexpectedly at the College and falls in love with a city that reminds him of his African home. The college sports world gushes over such storylines, and they should: They are rare.

“The city and the College grabbed me,” Baru admits. “It was just perfect.”

Upon his commitment to the College, the expectations for Baru were mammoth. He was the highest-ranked recruit ever in the College’s basketball history. Fans talked endlessly of how he would carry on the momentum of Andrew Goudelock, the College’s all-time leading scorer who had just been drafted by the Los Angeles Lakers. The Cougars were finally going to return the College to glory.

May the Best Man Win

We like players who win. We like dynasties. We also like underdogs … who win. Plain and simple, we like winners. A lot.

But what happens when our players don’t win? How should this team go down in the history books? When they haven’t hung banners from the rafters and we’re not filling out “CofC” on our brackets in March?

Easy: You remember their effort. And for this current Cougars team, you remember their relentless play. You remember that someone like Baru, despite nagging knee injuries, rarely sat out a practice, always giving you everything he had. You marvel at the fact that he was able to bring down more than 900 rebounds (the third most in the school’s Division I history) and score more than 1,000 points in four different offensive schemes, especially considering that every team game-planned against his offense first.

And you remember Baru for providing so many moments of basketball elation. The ear-splitting smack of the ball against his hands. His 7.5-foot wingspan that sent shots careening out of bounds. His uncanny interior passing. His ability to take a charge in crucial moments of the game. His signature, two-dribble, fade-away jumper in the paint. His monster dunks. And, of course, his gigantic smile, on and off the court.

And you remember Baru for providing so many moments of basketball elation. The ear-splitting smack of the ball against his hands. His 7.5-foot wingspan that sent shots careening out of bounds. His uncanny interior passing. His ability to take a charge in crucial moments of the game. His signature, two-dribble, fade-away jumper in the paint. His monster dunks. And, of course, his gigantic smile, on and off the court.

“I wish I could clone him,” says Marcia Snyder ’93, assistant dean of student learning and accreditation for the School of Business and Baru’s advisor as an international business major. “I wish all students could be as dedicated as he is. He does struggle, but he never gives up. He works and works until he masters something.”

“He is a special kid,” finance professor Mark Pyles agrees. “He was always there. If the team had gotten in at 6 o’clock that morning, he was still in class by 10. He never made excuses. He never got behind.”

Amir Abdul-Rahim, who was an assistant coach at the College during Baru’s sophomore and junior years, applauds Baru the student-athlete, emphasizing the word student: “This game teaches work ethic, discipline and structure. Adjehi understands that those lessons will make you successful in life. He understands the importance of never being late for class or practice. I wish you could make a statistic for that.”

But they don’t. And that’s a pity.

What we have in a player like Baru is a champion redefined. A figure whose contributions to the College are a poetic mix of pain, persistence and passion. This is the true portrait of a champion: It’s someone who’s tough, both mentally and physically; someone who may fail, but gets right back up, again and again; someone who puts team above self; someone who, in Coach Grant’s words, discovers his “treasure” and uses it; someone who gives maximum effort no matter the score, no matter the record.

Someone who has gone all out … all out. Someone like Adjehi Baru. A true winner, in every sense of the word.