For a few years now, music professor Blake Stevens has taught a Maymester course on the Beatles, exploring their songwriting craftsmanship as well as their impact on popular culture. Studying “Love Me Do” to “Here Comes the Sun,” today’s students discover the historic power of the Fab Four and leave the class no fool on the hill.

by Blake Stevens

Late in the semester in my Beatles class, as we were exploring the surreal territory of the White Album, a student asked in exasperation, “Why do they always have to be so weird?”

She had singled out an aspect of the Beatles that makes them surprising and even unsettling after 50 years: They were indeed weird, with their uncanny ability to assimilate the musical styles around them and transform them in unexpected and provocative ways. Looking back now, all these years later, we can really appreciate how they accomplished a nearly impossible feat: They managed to create an exceptionally popular body of music that challenges the prejudice that rock music is disposable, merely fashionable or commercial and lacking in craft, complexity and ambiguity.

This prejudice is still alive and kicking in some musical quarters. Yet if we exclude John Lennon and Paul McCartney from a tradition that embraces Schubert, Schumann, Varèse and Stockhausen, we miss their most compelling achievement. By the force of their imagination and their ability to shuttle across the popular- and art-music cultures of their day, the Beatles radically changed what it meant to produce “popular” music and what it meant to be a “rock ’n’ roll band.” Their work dismantled the all-too-easy assumption that popular music can’t achieve the cultural and even spiritual significance that we expect of “art.”

This challenge to academic conventions is one of the many reasons why the Beatles’ music is so rewarding to study and teach. It’s so closely bound up with the political and cultural transformations of the 1960s that it opens new perspective onto the entire period. A survey of the Beatles’ career introduces the study of sociological and aesthetic issues in musical production in the way that Jean-Baptiste Lully’s operas illuminate court life and tastes under Louis XIV, or that Mozart’s piano concertos and operas lead us into the world of 1780s Vienna.

Leaving history aside for the moment, I am always struck by how immediate a presence the Beatles have in the lives of students today. When their music is playing, it seems that generational divides and historical distance melt away.

Just watch footage of that iconic moment when the group first appears on The Ed Sullivan Show in February 1964. Through the black-and-white screen of stale comedy routines and stilted advertisements for shoe polish and shaving cream, the young musicians leap forward with astonishing immediacy, singing “All My Loving” and “She Loves You” as if they belong to our moment. Even to today’s students – now removed by two generations – the music’s vitality remains current.

If it’s so timeless – so relevant from generation to generation – why do some students find the Beatles’ music so weird? That observation has a lot to do with the wide range of the Beatles’ music, pushing in multiple directions. It would be impossible to capture this range in a short essay or even in a full semester of close study. Every fan likely gravitates at various times toward a particular period or moment in the Beatles’ career – for instance, toward the early, hard-driving and visceral rock ’n’ roll with its roots in dance clubs, or toward the more lyrical and introspective songs on Rubber Soul. I feel sure students will come to appreciate even the “weirdest” and most experimental of the Beatles’ repertoire at some point along the way.

As for me, I currently find myself drawn to the period in which the group first retreated from live performance, when they essentially became composers in the studio as opposed to concert performers. At this point their contact with their audience started to loosen, and they began to create introspective, mindful soundscapes, exploring themes of alienation and loss.

This was largely new territory for the legions of teenagers who had drowned out the group’s live performances with their screams. With Revolver in 1966, the group shifted its concerns to questions of the self and the depiction of complex states of consciousness, linked – but not limited – to psychedelic experiences. Most critically, they devised musical techniques to draw the listener into these states. If most of their early songs, from Please Please Me to Help!, used the instruments to carry a beat and propel the body into motion, the group was now approaching instrumental arrangements as a part of integrated poetic and dramatic structures. Perhaps for the first time in popular songwriting, we hear musical analogues (and not merely reflections) of states of consciousness.

The first four songs on Revolver map out this new territory. With “Taxman,” the band is no longer presenting itself as a purveyor of fantasy and electrified libido, but rather as a critic of the tax code and the politicians who control it. “Eleanor Rigby” sketches a narrative of the loneliness and death of an individual, hinting too at the broader disenchantment of modern life (“No one was saved”). The music of “I’m Only Sleeping” trails the meandering course of the daydreaming mind: Consciousness gradually becomes unmoored and seems to “float upstream,” while a guitar solo unravels backward in time – just one of many random ideas floating around inside the poet’s mind. Finally, a new perspective of love is achieved in “Love You To,” one that is aware of life’s inevitable end but still hopes to “make love singing songs.” The razor-edged drones of the sitar and tambura, however, keep the listener’s mind focused on the bitter reality.

And if the Beatles’ depiction of mental landscapes often takes the form of random bits of noise and music (e.g., the collages that end “Strawberry Fields Forever,” “Good Morning Good Morning,” “A Day in the Life” and “I Am the Walrus”), this kind of experimentation culminates in “Revolution 9” on the White Album: surely the least liked but most radical track on the double album. Its full significance emerges when it is placed within the history of experimental music, leading from the Italian Futurists, who translated the noises of modern life into sound art, and John Cage, who allowed for chance in musical creation and performance. Lennon himself described “Revolution 9” as the “drawing of revolution”; it materializes the conscious awareness of a violent revolution that is only hinted at in the song “Revolution.”

The Beatles’ exploration of these themes and states makes their music both perennially strange and relevant: Their songs don’t merely reflect, as with a mirror, the self and the world – but they create a sound world that absorbs the listener into that experience. Their music is at once a “mirror of society” and a “way of perceiving the world,” to borrow an expression from the theoretician of noise Jacques Attali.

But these strange moments appear alongside – and even erupt through – the more traditional, straightforward rock ’n’ roll songs, mixing the avant-garde with the immediately accessible in ways that continue to puzzle and inspire us, that continue to get us to think in one moment and dance in another.

Maybe their music is weird. But that’s exactly what keeps us listening.

– Blake Stevens is an associate professor of music history.

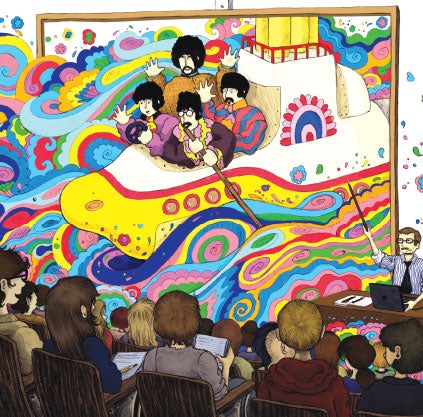

Illustration by Allison Conway