The College’s history reads like a novel at times: larger-than-life personalities and dramatic events in a setting of beauty and change. During one of its darkest financial chapters, several people worked behind the scenes to save the College. While their solution may not have been realized, their effort reveals the deep love so many have had for this special institution.

by Michael Mercurio ’73

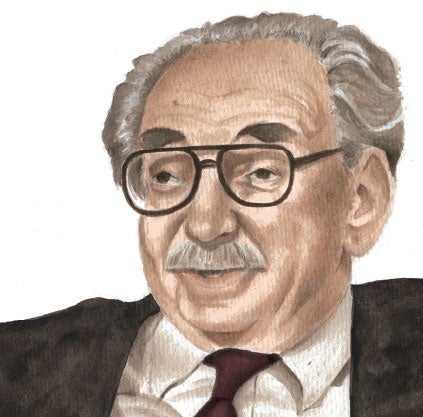

It was against the backdrop of the bloody Civil Rights movement and the disastrous Vietnam War that I first met George Heltai in 1967. A mutual friend, Professor Michael Thorn, who was a member of the history department, arranged for us to meet in Thorn’s small apartment in the then-blighted area of Ansonborough.

I was in the insurance business at the time, and my company had just completed a large loan for the construction of a new Piggly Wiggly grocery store on Meeting Street. I have no idea how Professor Thorn had knowledge of the loan for the Piggly Wiggly, but he was certainly aware that I worked for the same company, and that I was a leading sales associate who knew some of the major players.

I was completely unfamiliar with the College at that time. The only person I knew there was Professor Thorn. I had lived in Charleston since 1962, as a U.S. Marine guard at the naval base, and then had joined the insurance company in 1964. My worldview was narrow, to say the least. And all I knew of George Heltai was what Professor Thorn had told me: that George had been a high-ranking official in the communist party in Hungary and had been incarcerated after he’d fallen out of favor with party members. Subsequently, he’d escaped with his family during the 1956 Hungarian revolution.

When we met, after cordial greetings on both sides, we immediately sat down and lit up our smokes: me, my Marlboro and him, his cheroot. It became clear that George was indeed a worldly man – and also a bit eccentric, and passionate about the study of the humanities. I had a hard time understanding what George was saying because of his thick accent and the cheroot that seemed never to leave his lips, even when it went out. But I was able to learn about his and President Walter Coppedge’s vision of turning the then-private College into one of the most prestigious liberal arts schools in the country. For this, the institution would need a ton of money.

It was so long ago – I can no longer remember the millions of dollars that would be needed, but I do recall that it had to be enough to build a new library. The old one – Towell Library – was tiny and ill-stocked, built for a 19th-century population of students and faculty. New dormitories and teaching facilities would also have to be constructed to accommodate a much greater school enrollment – estimated to be four times that of the College in the 1960s, when it stood around 500.

Despite the obvious hurdles, I was impressed and excited by the idea, especially when George told me that he had assembled a cadre of world-renowned professors who would be willing to come to the school for a modest salary to teach in an environment of small classes taught in the Socratic tradition. So off I went, with five years of the institution’s financials to study, to prepare a persuasive argument for obtaining the monies needed to make the dream come true.

I examined the financial statements, trying to make sense of them so that, when I first presented the idea to my company, I would be able to discuss them intelligently. Unfortunately, the financial statements were lackluster, to say the least.

Believing that I must have misinterpreted the information on endowments to the College, I called Thaddeus Street ’35, a former member and chairman of the Board of Trustees. I never had the pleasure of meeting the gentleman; all conversations we had took place by telephone.

“Mr. Street,” I asked, “am I correct in believing that the endowments for the past five years have amounted to only $70,000?”

“Yes,” he replied with a note of chagrin. “Mr. Mercurio, you have to understand that although Charlestonians take great pride in our institution, it is quite another thing to get them to open their wallets and support it.”

Aware of the dire straits the school was in financially, I believed that seeking a loan from my company was a Hail Mary play to keep the College private by establishing an elite academic environment. But I was still determined to make the deal work, so I took off for Jacksonville, Fla., where my company’s headquarters was located, to make the hardest sales pitch of my life. I had serious doubts that the company would make the loan, but was determined to give it my best shot. In the end, my strategy was based on the premise that the loan would represent a terrific opportunity for the company to make a difference in the community, and enhance both their philanthropic reputation and, hopefully, increase their business success in Charleston. I had them going for quite a while.

It took three months of back and forth before a polite letter arrived one day informing us that the College was indeed a fine institution, but at this time the company, regrettably, was unable to make the loan.

We were all, of course, crestfallen. Not too long thereafter, when Ted Stern assumed the presidency, it was announced that the College would be joining the state system. However, George and others managed to keep their dream alive in small part by creating the honors history and English programs, and I became one of the lucky beneficiaries of their efforts when I enrolled at the College in 1969 at George’s urging.

I was 28 years old, quite a bit older than most of my class. The program was intense and extremely challenging. We began with approximately a dozen students, and by the end of the second and last year, the class size was inevitably reduced. Nevertheless, the knowledge and experience garnered from the program helped immensely in honing my intellectual skills as well as those of others.

With my degree in hand, I had intended to head for law school. However, life intervened when my daughter, Lisa, was born. Then, I began a new career in real estate with the Arthur Ravenel Jr. Company (led by Arthur Ravenel ’50). The degree gave me social respect that opened many doors; I became very successful in business and a force in politics.

I cannot help but wonder how the life of the College – and Charleston itself – might have been changed if Heltai’s dream had been realized.

– Michael Mercurio ’73 is a retired real estate broker and restaurateur who lives in Las Vegas. He recently published the novel A Charleston Yankee, set in the Holy City in the 1960s. Professor Heltai served as the inspiration for one of the novel’s characters.

Illustration by Joy Halstead