It is an unwelcome fate, perhaps only better than dying in combat or suffering severe injury. Captured soldiers who are made into prisoners of war often endure humiliation, abuse and neglect during indefinite wartime detentions. In a best-case scenario, POWs are treated humanely despite the curtailing of their freedom. In a worst case, POWs are tortured, starved, enslaved or executed by their captors.

It is an unwelcome fate, perhaps only better than dying in combat or suffering severe injury. Captured soldiers who are made into prisoners of war often endure humiliation, abuse and neglect during indefinite wartime detentions. In a best-case scenario, POWs are treated humanely despite the curtailing of their freedom. In a worst case, POWs are tortured, starved, enslaved or executed by their captors.

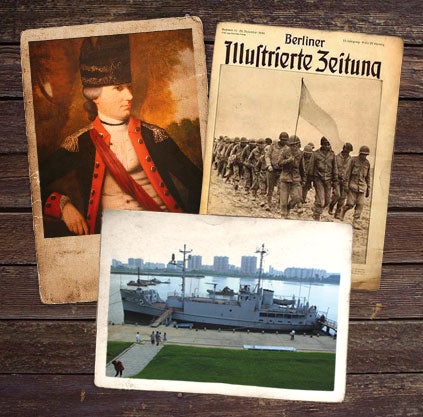

Throughout American history, a number of men associated with the College have spent portions of their lives as POWs. During the Revolutionary War, the British imprisoned many of South Carolina’s most prominent citizens and patriots. Some of these patriots later became the College’s earliest supporters and trustees.

In the Civil War, one of the Confederacy’s youngest officers, Lt. Henry Elliott Shepherd, was captured at the Battle of Gettysburg and imprisoned on Johnson’s Island, Ohio. Twenty years later, Shepherd became president of the College.

In World War II, Sgt. Alvin Skardon ’33 was captured by German forces and shuttled between prison camps until war’s end. And, in 1967, a sailor named Steve Robin was aboard the USS Pueblo spy ship when it was captured by North Korea. After his release, he eventually took classes at the College.

Each of these POWs had different experiences in confinement. Some suffered indignity only; others were routinely beaten and denied sufficient food and clothing. None knew when, or even if, they might return home to the company of loved ones. Here are their stories.

Thomas Heyward, Arthur Middleton, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney and Edward Rutledge, Patriots

Conflict: The American Revolution

Capture: Charleston, S.C., August 27, 1780

Imprisonment: Charleston and St. Augustine, Fla.

(clockwise, from top): CofC founders Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, Edward Rutledge, Arthur Middleton and Thomas Heyward

In May 1780, following the month-long Siege of Charleston, more than 5,000 American troops surrendered to British forces during the American Revolutionary War. For the British, the successful siege posed some problems, chief among them, how to accommodate such a large number of prisoners of war.

The British solution, in effect, was to scatter the prisoners, with some soldiers and unranked militiamen kept aboard prison ships in Charleston Harbor or within city barracks that would, after war’s end, serve as the first classrooms for the College.

American officers were treated in superior fashion. The British permitted officers to return to their homes on parole so long as they promised not to cause trouble. Such was the fate of College founding father and framer of the Constitution Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, who was paroled to his Snee Farm Plantation. Other officers, such as fellow College founding fathers and signees of the Declaration of Independence Thomas Heyward and Edward Rutledge, were also paroled to their homes and allowed to walk freely about Charleston.

More than three months after the fall of Charleston, the British suddenly arrested 29 of these officers and transported them by ship to St. Augustine, Fla. British commanders claimed that the American prisoners of war had violated their parole by continuing to instigate rebellion. One of these prisoners, Josiah Smith Jr., complained in a diary of “the Severe manner in which we were taken up and the Scandalous method made use of in conveying us from our Habitations.”

Despite the patriots’ protests, one could consider the British merciful in their punishment.

“The British had to do something,” says Carl Borick, director of The Charleston Museum and author of Relieve Us of This Burthen: American Prisoners of War in the Revolutionary South, 1780–1782. “Really all the British were doing was getting them out of their hair. They could have been a lot worse.”

Upon arrival in St. Augustine, the American officers were allowed to rent homes within the city and walk freely within the heart of town. Though prisoners of war, the American officers, including Heyward, Rutledge and fellow College founding father and signer of the Declaration of Independence Arthur Middleton, who arrived in St. Augustine later, were allowed many privileges. They enjoyed their own quarters, ate good food, kept gardens, drank rum and were allowed to write and receive letters. The officers were even permitted to bring slaves, who would fish and catch oysters for their masters.

Despite these comforts, American officers were very sensitive to slights by the British and the Loyalists. According to Smith’s diary, the officers were incensed when they were made to answer to a twice-a-day roll call and when British troops mocked them by playing and singing “Yankee Doodle” during “druken froliks [sic]” through town.

In July 1781, about a year after many of the officers’ arrests and transport to St. Augustine, nearly all American prisoners of war in the South were released as part of a prisoner exchange between the United States and Britain. More than 60 American officers in St. Augustine were taken by ship to Philadelphia, where they could reunite with their families. As a condition of the prisoner exchange, the South Carolina revolutionaries and their families were prohibited from returning to Charleston.

American Revolutionary Josiah Smith Jr. on the journey he and some of the College’s founding fathers endured on a ship to St. Augustine: In going up to town, the Schooner unluckily grounded on the edge of a large Sand bank, over which the tide set so strong, and the coming home of her Anchor, we could not get her off, was therefore obliged to spend a very disagreeable night there with very little Sleep, among Sheep, Hoggs [sic] and Poultry, most of us being put to the necessity of laying on Deck, in the Sails, and in a large Boat alongside.

On having to submit to a twice-a-day roll call: This we cou’d not but look upon as a kind of fresh Insult to our Persons, as it not only carried a suspicion of our Honour, but also put many of us to the inconvenience for dancing attendance in the warm part of the day, when we woul’d rather be retired to our apartments, there to improve ourselves by Reading &c.– however humiliating such a measure must be to us, after some debate upon the matter, considering we were intirely [sic] power of the Commandant, and that our Noncompliance might Induce him to plague us more in some other way, We in the General Agreed to comply with the requisition, provided we were Served with the Order in Writing.

On passing the holidays in captivity: Being Christmas day a very good dinner of Roasted Turkeys & Pig, Corn’d Beef, Ham, Plumb pudding, and pumpkin Tarts &c was provided by our Mess. And having Invited the Mess at Parole Corner to partake thereof, we dined together Thirty in number very heartily, and many of the Company as merrily Spent the Evening by a variety of Songs &c.

On the relatively comfortable conditions of imprisonment in St. Augustine: The weather has been exceeding agreeable, some times a little Cool, but in general Warm, indeed very little Cold hath been felt here all this Winter, and have seen Ice but once, early in January. Vegetation here comes on rapidly, the Orange Trees thro’ught the Town being in bloom most of the present Month, and what is very remarkable, not only Blossoms, but Green and Ripe fruit are now to be seen on many of those Trees.

NOTE: Josiah Smith’s full account of his captivity is printed in the South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine, beginning with Vol. 33, No. 1, January 1932.

Lt. Henry Elliott Shepherd, Confederate States Army

Conflict: American Civil War

Capture: Battle of Gettysburg, Gettysburg, Pa., July 3, 1863

Imprisonment: Johnson’s Island, Ohio

(clockwise, from top): rough sketch of U.S. military prison on Johnson’s Island; aerial view of Johnson’s Island, CofC president Henry E. Shepherd with 1890-91 student body and Henry E. Shepherd as a Confederate officer

Henry E. Shepherd served as the College’s president from 1882 to 1897, increasing student enrollment, insisting on the continued teaching of Classics and overseeing the rebuilding of Randolph Hall and other buildings damaged in the earthquake of 1886. A native of North Carolina, he had previously been superintendent of education in Baltimore, and, before that, at age 17, one of the youngest Confederate officers during the American Civil War.

In 1863 Shepherd was captured at the Battle of Gettysburg. The wounded 19-year-old officer was soon taken by Union troops to a cotton warehouse in Baltimore that had been made into a makeshift hospital. After recuperating sufficiently, Shepherd was sent to a Union prison camp on Johnson’s Island, Ohio, within Lake Erie. The many prisoners who failed at escaping, Shepherd notes in his memoir, were “subjected to the most degrading punishments in the form of servile labor, scarcely adapted to the status of convicts.”

At war’s end, Shepherd was freed. Within three years he married and moved to Baltimore, where he began a career in education that would culminate with his presidency at the College.

Beyond being a respected administrator, Shepherd was a highly regarded scholar and author, having been educated at Davidson College, the N.C. Military Institute in Charlotte and the University of Virginia. Shepherd’s books include History of the English Language, Life of Robert Edward Lee and A Commentary Upon Tennyson’s In Memoriam, which Shepherd wrote with the help of the great British poet himself.

Shepherd died in 1929 and is buried in Baltimore.

Shepherd on his medical care in Baltimore after being wounded and captured at Gettysburg: The immense (hospital) structure was dark, gloomy, without adequate ventilation, devoid of sanitary hygienic appliances or conveniences, and pervaded at all times by the pestilential exhalations which arose from the neighboring docks. During the seven weeks of my sojourn here, I rarely tasted a glass of cold water, but drank, in the broiling heat of the dog days, the warm, impure draught that flowed from the hydrant adjoining the ward in which I lay. My food was mush and molasses with hard bread, served three times a day.

The use of anaesthetics, which had been known to the world for nearly fifteen years, was awkward, crude and imperfect. The surgeons of that time seemed to be timorous in the application of their own agency, and the carnival of horrors which was revealed on more than one occasion in the operating room, might have engaged the loftiest power of tragic portrayal displayed by the author of “The Inferno.” The gangrene was cut from my wound, as a butcher would cut a chop or a steak in the Lexington market; it may have been providential that I was delivered from the anaesthetic blundering then in vogue, and “recovered in spite of my physician.” Consideration originating in sensibility, or even in humanity, found no place in West Hospital.

On his imprisonment on Johnson’s Island: The rations upon which life was maintained for the latter months of my imprisonment were distributed every day at noon, and were as follows: To each prisoner one-half loaf of hard bread, and a piece of salt pork, in size not sufficient for an ordinary meal. In taste the latter was almost nauseating, but it was devoured because there was no choice other than to eat it, or endure the tortures of prolonged starvation. …

Vegetable food was almost unknown, and as a natural result, death from such diseases as scurvy, carried more than one Confederate to a grave in the island cemetery just outside the prison walls. I never shall forget the sense of gratitude with which I secured, by some lucky chance, a raw turnip, and in an advanced stage of physical exhaustion, eagerly devoured it, as I supported myself by holding on to the steps of my barrack. No language of which I am capable is adequate to portray the agonies of immitigable hunger. The rations which were distributed at noon each day, were expected to sustain life untill [sic] the noon of the day following. During this interval, many of us became so crazed by hunger that the prescribed allowance of pork and bread was devoured ravenously as soon as received. Then followed an unbroken fast until the noon of the day succeeding. For six or seven months I subsisted upon one meal in 24 hours, and that was composed of food so coarse and unpalatable as to appeal only to a stomach which was eating out its own life. So terrible at times were the pangs of appetite, that some of the prisoners who were fortunate enough to secure the kindly services of a rat-terrier, were glad to appropriate the animals which were thus captured, cooking and eating them to allay the fierce agony of unabating hunger. Although I frequently saw the rats pursued and caught, I never tasted their flesh when cooked, for I was so painfully affected by nausea, as to be rendered incapable of retaining the ordinary prison fare.

I had become so weakened by months of torture from starvation that when I slept I dreamed of luxurious banquets, while the saliva poured from my lips in a continuous flow, until my soldier shirt was saturated with the copious discharge.

The winters in the latitude of Johnson’s Island were doubly severe to men born and raised in the Southern States. Moreover, the prisoners possessed neither clothing nor blankets intended for such weather as we experienced. During the winter of 1863–64, I was confined in one room with seventy other Confederates. The building was not ceiled [sic], but simply weather-boarded. It afforded most inadequate protection against the cold or snow, which at times beat in upon my bunk with pitiless severity. The room was provided with one antiquated stove to preserve 70 men from intense suffering when the thermometer stood at fifteen and twenty degrees below zero. The fuel given us was frequently insufficient, and in our desperation, we burned every available chair or box, and even parts of our bunks found their way into the stove. During this time of horrors, some of us maintained life by forming a circle and dancing with the energy of dispair [sic].

NOTE: Shepherd’s recollections of capture are contained in his Narrative of Prison Life at Baltimore and Johnson’s Island, Ohio.

Sgt. Alvin W. Skardon ’33, U.S. Army

Conflict: World War II

Capture: Battle of the Bulge, Schönberg, Germany, December 19, 1944

Imprisonment: German POW camps at Mühlberg, Furstenberg and Luckenwalde

(clockwise, from top left) Alvin Skardon as a sophomore at the College in 1931, Skardon at Youngtown State University (where he taught from 1957 to 1983), German newspaper reporting on the capture of Skardon’s 106th Infantry Division and a scene from the Battle of the Bulge (where Skardon was captured)

Following his graduation from the College, Alvin Skardon ’33 worked for eight years at the Lady Lafayette Hotel in Walterboro, S.C., where he was a manager.

In summer 1941, Skardon was drafted into the Army during World War II, serving in the infantry, chemical warfare and field artillery. In November 1944, Skardon was sent to Europe as part of the 106th Army Division, which was occupying territory on the border of Belgium and Germany. Skardon and his fellow soldiers were under-equipped and ill-trained, but Army planners believed they were well insulated from a German attack and would see little fighting throughout the cold winter.

The Army planners were wrong. A week after arriving on the front lines, German forces began a daring counterattack through the Ardennes Forest, beginning the Battle of the Bulge. American forces suffered approximately 90,000 casualties in the ensuing weeks, including 23,000 soldiers who were captured or went missing. Many of these American POWs were soon marched deeper into Germany, away from the fighting. Eventually Skardon and his comrades were placed into train cars, which were very cold, very cramped and littered with horse droppings. Food, and especially water, were scarce. The POWs were placed in Stalag IV-B, a prison camp outside Mühlberg, filled with British POWs.

After two weeks, the American prisoners were transferred by train to Stalag III-B near Furstenberg. Two months later the prisoners were marched toward Berlin to Stalag III-A at Luckenwalde. Here the prisoners slept beneath large tents and received extremely sparse rations that left them near starving, though they occasionally received food parcels from the Red Cross. Skardon surmised that the Germans deprived them of substantial meals to keep them weak and easier to control, yet were careful not to starve the prisoners entirely, which might spark a revolt. Beyond being constantly hungry, Skardon and his comrades were infested with lice and had no access to bath facilities.

Though conditions were miserable, the Germans did not otherwise mistreat the American prisoners. In fact, Skardon says the prisoners became “chummy” with the guards, many of whom were old men who were veterans of World War I. The guards would trade food for cigarettes with the prisoners and warn them before a German officer was to make an inspection of the camp. Skardon says these guards knew Germany’s days were numbered and the war would soon be over.

In May 1945 Russian soldiers liberated the camp. Skardon had been a prisoner for six months and was emaciated. When Skardon returned to the United States, he discovered his brother, who had been a prisoner of war in Japanese-controlled Burma, had also made it home safely. After the war, Skardon earned his master’s degree and Ph.D. in history from the University of Chicago, where he taught for a number of years. Skardon also taught at Youngstown State University in Ohio. He died in 2002.

Skardon on his experiences in German POW camps, or stalags: Conditions were rather terrible. We had to sleep on the ground, just straw on the ground. We had thin blankets. We had minimal rations. The Swiss Red Cross complained again that we were not being fed enough for an average person to live on.

At the second prison camp that we went to, the Germans put us in a big cooler that was so cold that we had to walk around all the time to keep from freezing. Then when we got too tired, about twelve fellows would just sleep in a bundle with our overcoats over us.

We got what the Germans call coffee but it was definitely Ersatz, that is, artificial coffee, and it tasted terrible and did not have the bracing effect that coffee usually gives. That was breakfast. For lunch we had usually a piece of bread with some butter and for dinner we had usually six small potatoes and a cup of soup.

I managed to borrow books almost every day and read them. But when you were reading you had to walk around. You couldn’t remain seated, it was too cold. You would freeze if you remained seated.

Our contact with the Germans was almost exclusively through the one guard, an old man who had charge of four hundred prisoners. And he just walked around during the day with his rifle slung over his shoulder and, incidentally, we never found out whether the rifle was actually loaded or whether he had bullets or not.

It was easy to escape and easy to get through Germany. There were so many different nationalities in Germany and so many different uniforms that one more uniform made no great difference. In most cases you were not stopped until you got to the Swiss border, which was almost impossible to get through.

If you saw the guard come in, the first person who saw him was supposed to shout “Air raid! Whoooooo!” and go like that. The guards always seemed to think that was some way of showing them honor, because one day, the guard came in and no one said that because they didn’t see him, and he yelled out, “Ja, Ja. It’s me! Air raid! Whooooo!” Apparently he thought that was something that should be done.

On being liberated by the Russian Army: We were marched down to a hut and there were two lines: one, English prisoners, and one, American prisoners. And there were Russians inside registering us. We heard the English prisoners were furious. It turned out we were being registered by Russian WACs (Women’s Army Corps) while they were being registered by Russian men soldiers. They were saying, “The bloody Yanks, they always get the women and the liquor.”

Later on when the Russians liberated our camp, they just lined up all the men who were Russian prisoners and asked who had collaborated with the Germans, and if you were accused of collaborating with the Germans, they just stood you up against the wall and they shot the whole bunch down with machine guns … without any trial or investigation at all.

NOTE: Skardon’s recollections of World War II were documented by Youngstown State University’s Oral History Program through interviews in 1975 and 1978.

Petty Officer 3rd Class Steven J. Robin, U.S. Navy

Conflict: The USS Pueblo Incident

Capture: Off North Korea, January 23, 1968

Imprisonment: North Korea

(clockwise, from top) the crew of the USS Pueblo, 1969; Steve Robin (left) playing chess with Alvin Plucker during captivity; USS Pueblo docked in Pyongyang, North Korea and Steve Robin (upon his release from North Korea)

Steve Robin attended the College in the 1970s, about a decade after he and 82 other sailors were imprisoned by North Korea following the capture of the American spy ship the USS Pueblo. Robin, who died at age 62 in 2008, was a communications technician aboard the Pueblo, helping collect and analyze foreign electronic communications in a secure area within the ship.

In January 1968, the Pueblo was cruising off the coast of North Korea, eavesdropping on electronic communications, when North Korean sub chasers and torpedo boats suddenly surrounded the boat. The Pueblo claimed it was in international waters, but North Korea said otherwise.

When the Pueblo attempted to maneuver away from the North Korean ships, a sub chaser opened fire on the American vessel, killing one American sailor. Crewmembers aboard the Pueblo then began to destroy classified material as the outnumbered and outgunned American ship readied itself for surrender.

After capture, the Pueblo was escorted into the North Korean port of Wonsan, where the crew was then transferred to a train and taken to the capital of Pyongyang, where they were imprisoned in a building the Americans nicknamed The Barn. The Barn was not a place of pastoral pleasures, but rather pitiless punishment. There the crew was interrogated and tortured, even though many of them were clueless to the spy operations that had occurred within secure areas of the ship.

Seaman Earl Phares, who was a boatswain’s mate, says he and his fellow crewmen were forced to sit in chairs while they were beaten. Their captors whacked them with plastic flippers and two-by-fours. The North Koreans delivered karate kicks and smashed the American’s fingers with rifle butts.

Robin, meanwhile, was perhaps subjected to even more extreme torture because of his role as a communications technician, or spy, aboard the ship. Phares feels confident stating that Robin “got the living shit beat out of him,” as did many of the crew. Robin’s brother, Sherwin Robin, says his brother was made to walk on his knees on a rutted, wood floor, sometimes while holding his ankles. Steve Robin’s knees turned bloody on the floor and his skin grated away, revealing bone. When he stumbled, Sherwin Robin says, guards hit his brother with a two-by-four.

After about two months, the Pueblo crew was moved to a barracks within a North Korean army base. It was here that Robin, Phares and Petty Officer 3rd Class Alvin Plucker became roommates with five other men. The beatings continued, and conditions continued to be oppressive and miserable.

Food was horrible. The Pueblo crew was given three meals a day, each usually consisting of some combination of turnip soup, turnip greens, hard bread and hot, oily water that tasted fishy.

“It was nasty,” says Phares.

Sometimes, says Plucker, the men received something like catfish that the Americans nicknamed “sewer trout.” Other times, North Koreans were seen to urinate in the Americans’ food.

Predictably, the men suffered severe malnutrition, each losing a third of their body weight: Robin dropped from 210 pounds to 147; Phares withered from 180 pounds to 120; and Plucker, already a slight man at 131 pounds, was reduced to 98 pounds.

Diarrhea was a common ailment, and worsened by the fact that the sailors were deprived of toilet paper. The captives improvised by separating layers of cardboard and fashioning small squares of the coarse fiber to be able to clean themselves, albeit in painful fashion. A trip to the bathroom also required a dose of courage, as guards often kicked the Pueblo crew when they ventured to the toilet, as if the sailors were traveling through a gauntlet.

There were other humiliations. The North Koreans gave American sailors penknives to cut the grass on a soccer field outside the barracks. While doing this, some crew ate any earthworms they found, says Plucker, since they were so hungry.

The crew was allowed to read books and occasionally watch movies, though the books and films were all propaganda pieces denouncing the alleged imperialism of America. Phares would prop a book in front of his face and go to sleep behind it. It was one way to escape the incessant boredom.

“Sleep was our time away from Korea,” says Phares.

But sleep was only a partial reprieve. Bedbugs ravaged the men, resulting in blood-spattered bed sheets. Plucker moaned when he slept on account of the pain caused by the many beatings that bruised his ribs. Guards poked the feet of the sleeping American with bayonets to get him to quiet down.

The Americans retaliated against their captors subtly, mocking them in various ways the North Koreans could not appreciate. Most famously, the Americans routinely flipped their captors the middle finger, especially when they were photographed as part of North Korean propaganda efforts. When the North Koreans asked what the one-fingered salute meant, the Americans explained it was the Hawaiian good luck sign.

Eventually, the captors discovered the true meaning of the gesture. Infuriated, they began beating the crew with renewed vigor, leading the Americans to label this time period “Hell Week.”

The constant beatings, poor food and fear of death (the North Koreans conducted mock executions on some) caused much anxiety, making the Americans irritable and short-tempered, even with each other. But as time went on conditions improved to some extent, with the prisoners being allowed to attend a circus, for example, and share, among four people, treats like an apple or a piece of bread with butter.

Sometimes the Americans would squirrel away an apple to be enjoyed later, only to discover it missing. When they learned the guards were stealing their fruit, they began urinating on the apples and placing small, glass shards in the flesh, hoping the North Koreans would ingest the contaminated food.

“After a while,” Plucker says, “the apple stealing stopped.”

On December 23, 1968, following an apology by the United States, the Pueblo crew was released by North Korea and allowed to walk across the Bridge of No Return at Panmunjom, passing through the Korean Demilitarized Zone into South Korea. The crew of the Pueblo had spent 11 months in captivity.

The Pueblo, however, remains in North Korean hands and is the only commissioned Navy vessel held captive by a foreign power. The Pueblo is docked in Pyongyang and is a tourist attraction.