Charlie Paine may still be a budding preservationist, but that doesn’t mean he’s afraid to tackle a big project.

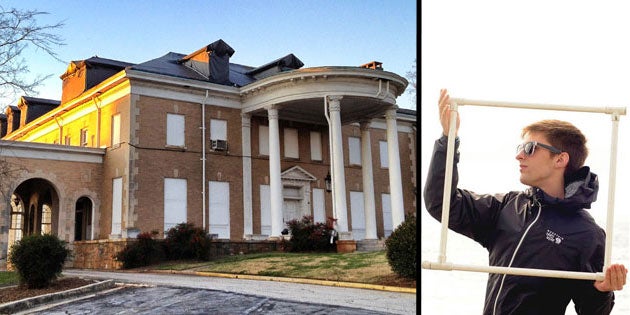

And by big, we mean BIG. The freshman historic preservation student has spearheaded a campaign in his native Atlanta to save Briarcliff, a 42-acre estate in the Druid Hills neighborhood that features a huge, dilapidated mansion built by Coca-Cola Co. heir Asa “Buddy” Candler Jr.

Candler, the son of Coca-Cola Co. founder Asa Griggs Candler, built the sprawling mansion in 1922. A few years later, he added to the home, building a massive, vaulted music room that contained an enormous Aeolian organ. During Candler’s residency, the property also featured elaborate greenhouses, a dairy operation, a menagerie of exotic animals and a swimming pool that was open to the public for a small fee.

After the Candler family sold the home in 1949, the property eventually housed the Georgia Mental Health Institute as well as a treatment center within the mansion for alcoholics and drug addicts. In 1998 Emory University bought the estate and began developing a satellite campus on the property. The mansion, however, remains unrestored and empty today, being used occasionally for filming movies such as The Divergent Series: Allegiant, a sci-fi film shot at Briarcliff in the spring of 2015.

Hollywood glamor aside, Paine is disappointed that Briarcliff has not been better maintained and restored. Since moving across the street from the estate with his family a few years ago, he became fascinated by the once-grand mansion. Paine began researching its history and brainstorming ways to save the structure. While in high school, he started the Save Briarcliff/Candler Mansion group on Facebook, which has been liked by about 1,000 people. Atlanta’s Creative Loafing newspaper took notice of the high school student, writing about Paine in April 2015.

But all the attention on the property has not yielded a solution to its future, at least not yet.

“Everyone in the community knows about it,” says Paine, “but no one knows what to do with it.”

Charlie Paine with a letter signifying his family’s Mediterranean-style Atlanta home, Villa Miraflores, is eligible for placement on the National Register of Historic Places.

Emory, for its part, says it maintains the mansion and has no plans to demolish it.

Paine, however, wants Emory to do more. He says he’s asked the university to place a preservation easement on the house, but to no avail.

Now at the College of Charleston, Paine remains committed to the mansion’s preservation. He will soon speak about the mansion at a Charleston-area retirement community, and he has plans to more aggressively lobby for Briarcliff, mentioning the need to create a website, petitions and yard signs that advocate for its future.

He’s also completed research on the property’s greenhouses, discovering blueprints for the structures at the New York Botanical Society.

“I didn’t think you could have such detailed plans for a greenhouse,” admits Paine.

As he broadens his preservation perspective in Charleston by volunteering as a tour guide during the Preservation Society of Charleston’s Fall Tour of Home and Gardens, Paine continues to think up ways to save the mansion across the street from his family home in Atlanta.

It may take a lot of money and creativity to restore the mansion to its former glory, Paine knows, but that’s no reason to give up the fight.