Shortly after he began teaching at the College of Charleston in 2011, Associate Professor of Teacher Education Jon Hale began taking his students to Emanuel A.M.E. Church as part of a course on the history of Charleston and the civil rights movement.

“We’d go to the church basement and hear from Mr. Willi Glee, the church archivist,” Hale recalls. “The lecture focused on the history of the church and the connection between the church and politics. I wanted the students to see that the Southern church was integral to the civil rights movement.”

Hale strives to provide opportunities for his students to get up close and personal with the living history that surrounds them in Charleston. And when it comes to discussions about slavery, abolitionism, and civil rights, few churches in the South are more important to that conversation than “Mother Emanuel,” which is the oldest A.M.E. church in the South and has been the epicenter of the black community in Charleston for generations.

It’s also believed that the church’s history made it a target of alleged shooter Dylann Roof. Hale went numb when he heard the news that a shooting on June 17, 2015, had claimed the lives of nine of the church’s members, some of whom Hale knew through his class and community work.

But before he could properly grieve, there was work to be done. As a scholar on the history of American education during the civil rights movement, Hale spoke with reporters around the country wanting to know more about the church’s history and why it had been singled out. The next few days were a blur as he conducted interview after interview. He struggled to keep his emotions in check as he did his best to place the church and its importance in proper historical context.

Gail Falk teaching Freedom School students in Meridian, Mississippi. (Mark Levy Collection, Queens College Rosenthal Library Civil Rights Archive, courtesy of Mark Levy)

For Hale, the shooting signaled a turning point in his career. He had been active in education reform and research before the tragedy, but the profoundness of the loss at Mother Emanuel spurred him to double-down. As an educator, as a teacher of teachers, he took it personally that the education system had failed to reach a kid like Roof.

“There is a point where you feel you could have done more,” Hale says. “What if you would have reached teachers who could have reached Dylan Roof? It was ignorance that caused that, and ignorance is addressed by education. He was in a school where he did not learn this history. We are all responsible. It’s part of a much larger problem that I see.”

Hale does not fit the traditional mold of an African American studies scholar. He is white and relatively young. He’s used to the double-takes and the skepticism he encounters as he travels around the South conducting interviews and research for books and articles. A Midwesterner, he’s not insulted when the first questions he’s asked are where he’s from and what his motives are. In fact, he welcomes such scrutiny.

“There is a lot of skepticism, and there should be, because there’s a really long history of Northern whites who think they know what’s best and speaking for African Americans as part of a larger history of paternalism. So I always try to be conscious of that,” he says.

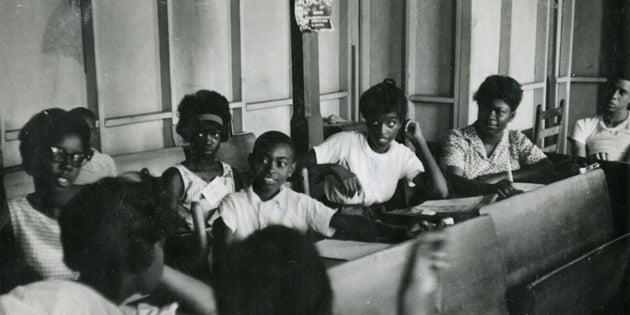

A Freedom School class in Meridian, Mississippi. (Mark Levy Collection, Queens College/CUNY Rosenthal Library Civil Rights Archive, courtesy of Mark Levy)

In the wake of the shootings, Hale believes it’s more important than ever that white Americans take a hard look at an education system that fails to adequately deal with the issues of racism, bigotry, cultural misunderstanding and insensitivity.

“W.E.B. Du Bois and Frederick Douglass argued that race is a national issue and racism is an issue that everyone has to address. Especially now after A.M.E., one thing that we knew before but that is really coming to the forefront is the fact that white people have to go through the process of understanding our history of slavery and segregation and race and how white people obviously played a role in that. So it’s not just leaning on people of color to tell us what to do. White people have to do this work in our own communities, too.”

For Hale, this “work” takes the form of scholarly research, filling gaps in our understanding of historical events and turning a spotlight on forgotten or underappreciated parts of African American and American history. Which is what he hopes to accomplish with two forthcoming books.

The first book, The Freedom Schools, was published by Columbia University Press in June 2016 and details the history of 41 schools that were created in 1964 as part of the Mississippi Freedom Summer.

Where many accounts of the civil rights movement focus on national figures and college students, Hale’s book highlights the often overlooked contributions of middle school and high school students and teachers.

“These schools were training middle and high school students to become activists. (The schools) were in unconventional spaces like churches and homes,” says Hale. “The Klan was attacking these places so they had to be clandestine about where they were held.”

His research on the Freedom Schools eventually led him to expand his view to other civil rights era high schools across the South. After moving to Charleston, he came across a reference to the first sit-in in Charleston that took place at the old S.H. Kress & Co. department store building.

“Because Mississippi was so active with civil rights protests, people thought little had happened in Charleston,” says Hale. “My research showed that students at Burke High School started that protest.”

Eddie James Carthan in the Mileston Freedom School in Mississippi, 1964. (Photo by Matt Herron, Courtesy of Eddie James Carthan)

And soon, the idea for another book took root. Learning to Protest highlights the significance and history of black high schools during the civil rights movement. Hale is writing the book as part of a prestigious fellowship from the National Academy of Education and the Spencer Foundation.

Hale has traveled extensively across the South to piece together the history of 12 schools in South Carolina, Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi and Virginia. Among the schools that will be featured in the book are Burke High School and the Avery Normal Institute (now the College’s Avery Research Center), which functioned as a normal school and a high school from 1865 to 1954.

Featuring prominently in the book will be a series of oral history interviews with black high school students who were active in the civil rights movement.

In addition to publishing, Hale is also active with education reform efforts in Charleston through an organization he helped found called the Quality Education Project. While his volunteer work with the organization is separate from the College, Hale believes that advocating for public education and equitable school reform are part and parcel of the responsibility of all educators.

One of the group’s initiatives involves working with white teachers and developing curriculum to discuss race in school classrooms throughout Charleston, where 55 percent of students are of color and 87 percent of teachers are white. This curriculum, “Human Rights and Civic Action,” has been approved by the state and will be launched at North Charleston High School in the fall.

“People in general are uncomfortable talking about race, which means it’s not being taught in the classroom, which can help explain a Dylan Roof incident,” says Hale. “That’s not the root; it’s just part of the context.”

This summer of 2016, as he works to complete his book, Hale is looking ahead to the fall semester when he will once again teach his course on the history of Charleston and the civil rights movement. This year’s class will be taught as part of the College’s First Year Experience program, meaning that all of the students will be freshmen.

While only a year has passed since the tragedy at Mother Emanuel and emotions remain raw, Hale plans to teach the class the same way he did before the shootings, with a visit to the church.