On the last Monday of May each year, communities gather at parks, churches, cemeteries and monuments to memorialize those soldiers who have died in service to our country.

Prayers are said. Hymns are played. Flags are placed at headstones of the fallen and wreaths are laid at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery outside Washington, D.C.

Memorial Day officially dates back to an 1868 ceremony in Decatur, Illinois, when Maj. Gen. John A. Logan of the Grand Army of the Republic, a fraternal organization composed of veterans of the Union Army, called for a national “Decoration Day” to adorn the graves of the Union dead with flowers.

The club house at the race course where Union officers were confined. (Photo from the Library of Congress.)

But in recent years the origins of how and where Decoration Day began has sparked lively debate among historians, with some, including Yale historian David Blight, asserting the holiday is rooted in a moving ceremony held by freed slaves on May 1, 1865, at the tattered remnants of a Confederate prison camp at Charleston’s Washington Race Course and Jockey Club – today known as Hampton Park. The ceremony is believed to have included a parade of as many as 10,000 people, including 3,000 black schoolchildren singing the Union marching song “John Brown’s Body” while carrying armfuls of flowers.

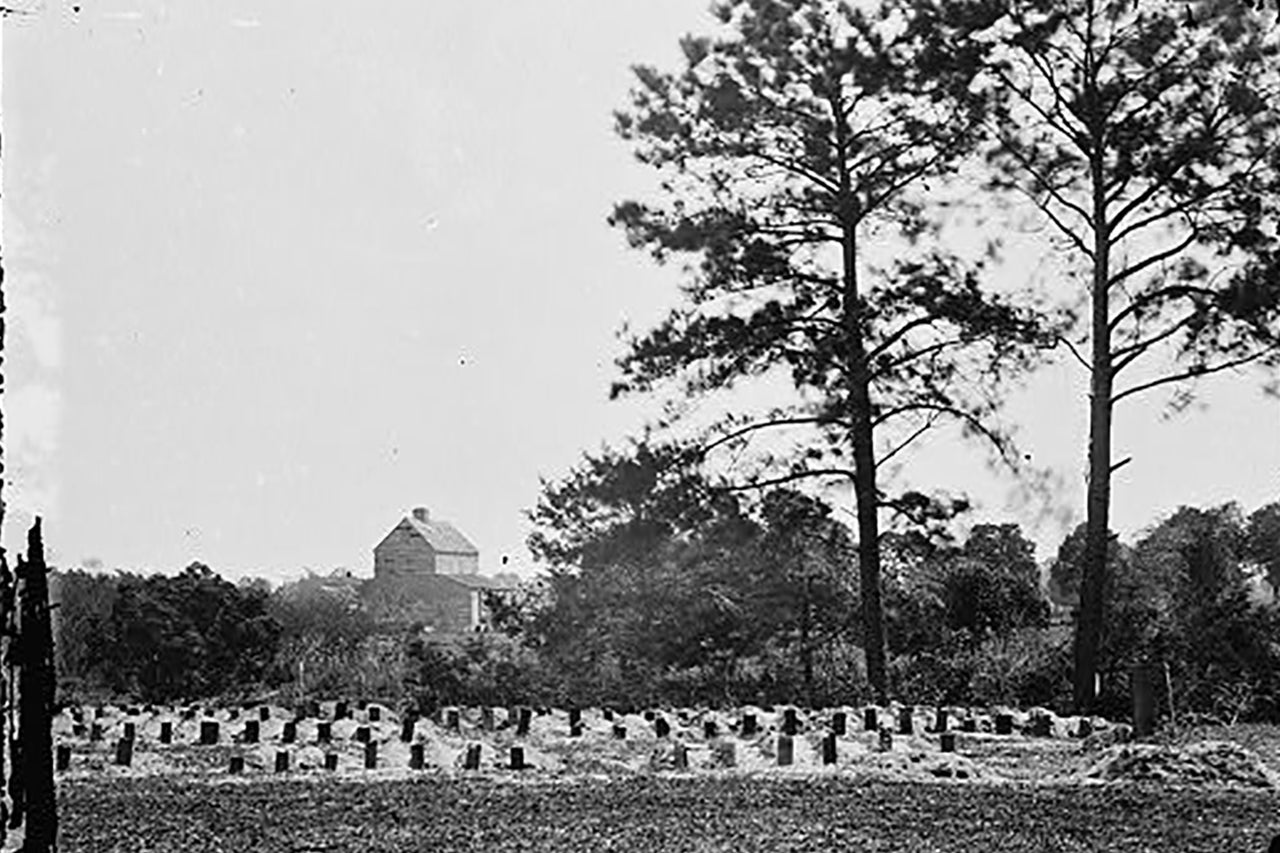

Adam Domby, assistant professor of history at CofC, believes more importantly than whether Charleston’s Decoration Day was the first, is the attention Charleston’s black community paid to the nearly 260 Union troops who died at the site. For two weeks prior to the ceremony, former slaves and black workmen exhumed the soldiers’ remains from a hastily dug mass grave behind the race track’s grand stand and gave each soldier a proper burial. They also constructed a fence to protect the site with an arch way at the entrance that read “Martyrs of the Race Course.”

“The dead prisoners of war at the race track must have seemed especially worthy of honor to former slaves,” he says. “Just as former slaves had, the dead prisoners had suffered imprisonment and mistreatment while held captive by white southerners.”

Writings of a Union soldier, unearthed by Blight at the Harvard University library, referenced the 1865 event in Charleston. That sent the Yale history professor to search for more detailed accounts of the ceremony, which led him to the archives of the College’s Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture where he found a newspaper account documenting the event. More research followed and in 2001 Blight authored a book entitled Race and Reunion, which included a detailed account of that 1865 Decoration Day ceremony in Charleston.

Domby says there is some debate as to whether there are any connections between the Charleston ceremony and the 1868 Decoration Day in Illinois. Some people, he says, have argued there are no direct links between the two ceremonies.

“As is often the case with traditions that evolve over time, it is hard to put a finger on exactly which came first and who decided what the tradition should include,” Domby says.

An 1865 drawing depicts the fence around the cemetery, noting the phrase at the entrance “Martyrs of the Race Course.” (Photo from the Library of Congress.)

Not surprisingly, many white southerners who had supported the Confederacy, including a large swath of white Charlestonians, did not feel compelled to spend a day decorating the graves of their former enemies. It was often African American southerners, says Domby, who perpetuated the holiday in the years immediately following the Civil War.

“African Americans across the South clearly helped shape the ceremony in its early years,” he says. “Without African Americans the ceremonies would have had far fewer in attendance in many areas, making the holiday less significant.”

A parallel holiday, called “Memorial Day,” was observed by Confederate sympathizers. It wasn’t until after World War II that the holiday was more commonly called Memorial Day, but federal law didn’t formally recognize the day by that name until the late 1960s.

But the debate of how our Memorial Day traditions began doesn’t diminish the significance of what happened on that warm May day in Hampton Park 152 years ago.

“There is still a clear cultural link between the 1865 ceremony and later ceremonies,” says Domby, noting that African Americans across the South were instrumental in shaping the early ceremonies for Decoration Day. “That cultural link is what interests many historians including David Blight and myself. So, while the ceremony in Charleston may not have been the direct inspiration for Logan, the 1865 ceremony clearly shared many of the meanings that would come to characterize future ceremonies.”

Featured image of the Union cemetery at Washington Race Course from the Library of Congress.