Skyscrapers and the Virgin Mary frame the scene. UFOs buzz overhead. An agricultural worker kneels – out of awe, exhaustion, or both – among neatly planted rows terminating in a distant U.S. Capitol. Tarascan symbols, Mesoamerican sculpture, and the Seal of the Department of Homeland Security dot the landscape. Through a tangle of splintered staves and steel beams writhes a rattlesnake, a pair of gilt calaveras in its clutch. A menacing Statue of Liberty looks on astride a $100 bill.

“Guadalupana Torch” is the piece’s title, painted by Cornelio Campos, a Carolinian by way of Michoacán, Mexico. It is among a cache of materials featured in Las Voces del Lowcountry, a new digital exhibit spotlighting the Carolina’s oft-overlooked Latino communities.

Weaving together oral histories, photographs, art, and other primary sources, Las Voces del Lowcountry explores Latinos’ contributions to the cultural and economic life of the region, as well as their struggles with poverty and discrimination.

Guadalupana Torch, painting by Cornelio Campos, Durham, North Carolina, appears in the Las Voces del Lowcountry digital exhibit.

From harrowing travels across the U.S. border to public demonstrations against South Carolina’s S.B. 20 identification policy in federal court, these are the stories of Charleston’s Latino communities expressed in their own words and images.

“Stories are our starting point,” says Marina López, co-author of the exhibit with Kerry Taylor. “The hope is that they remind people that we are talking about human beings,” not disembodied facts and figures.

Las Voces del Lowcountry is organized thematically, documenting the struggles of working class immigrants and their children, the impact of immigration policies on their lives, and the development of Latino social and political organizations.

“This framework provides an opportunity to explore their experiences with depth and nuance, and to honor their struggles to make a better life for themselves and their family members,” adds Taylor.

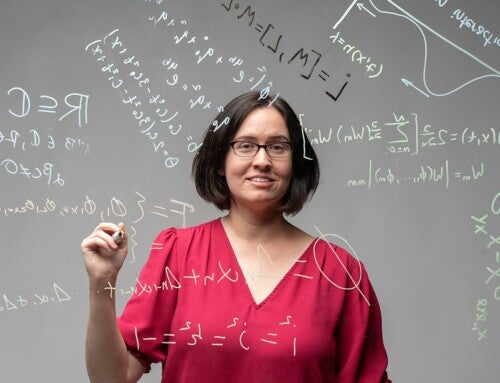

Addlestone Library’s digital projects team curates Lowcountry Digital Library and Lowcountry Digital History Initiative projects, including Las Voces del Lowcountry. (Photo by Reese Moore)

The exhibit is produced by the Lowcountry Digital History Initiative (LDHI), an award-winning digital public history project hosted by the Lowcountry Digital Library (LCDL) at the College of Charleston. It marks LDHI’s first bilingual effort, reflecting the initiative’s inclusive approach to public history and its commitment to highlighting underrepresented race, class, gender and labor histories.

“LDHI is thrilled to work with Marina and Kerry on this exhibit not only to provide a window into Latinos’ experiences here in the tri-county area, but to also make the exhibit bilingual,” says Leah Worthington, project chief of LDHI and LCDL. “With interviewees’ stories available in Spanish and English, voices of the Lowcountry’s Latino communities will reach individuals across the region and beyond.”

Las Voces del Lowcountry is made possible through the work of graduate assistants from the College of Charleston-Citadel Graduate History M.A. Program. Empowered with curatorial and administrative experience in digital humanities, students worked to – in the words of the exhibit’s coauthors – “introduce Charleston to their newest neighbors.”

The region’s first immigrants arrived more than 50 years ago, drawn to seasonal employment in the tomato sheds of Johns Island and nearby farms.

Since the 1960s, say Taylor and López, thousands of natives of Mexico and Central America have worked in local agriculture. Over the years they were joined by smaller communities of Puerto Ricans, Argentinians, Colombians, and Brazilians, many fleeing for their lives from political instability, government repression or military strife. Today, more than a quarter million Latinos call South Carolina home, with nearly 36,000 in the Charleston-Berkeley-Dorchester area. As of fall 2017, 5.3 percent of CofC students identified as Hispanic.

RELATED: Read about the launch of the College’s first Latin fraternity.

And yet Latinos’ stories of tragedy and triumph are largley unknown to many Charlestonians.

Las Voces del Lowcountry is a small step toward capturing unique moments in the development of Latino communities in Charleston and at the College.

“The exhibit is a wonderful start,” says John White, director of LDHI and dean of libraries at the College of Charleston. “But there is still work to be done by the region’s archives and museums to collect, preserve and make available materials related to Latino history and culture in the region. I hope this project serves as a catalyst for more engagement with Latino communities from Charleston’s cultural heritage professionals.”

Las Voces del Lowcountry – along with nearly two dozen other digital exhibits produced by LDHI – is freely available at ldhi.library.cofc.edu. To browse 100,000-plus images in the Lowcountry Digital Library, visit lcdl.library.cofc.edu.

Featured image courtesy of Las Voces del Lowcountry: Immigration Reform Rally, photograph by Marcela Rabens, Charleston, South Carolina, April 10, 2006.