Nearly 100 years ago, Harry Hervey’s works lined bookshelves in the Holy City and across the country. Today, the author, adventurer and literary trailblazer is all but excluded in popular memory and the gay literary canon.

What explains this vanishing act?

Harlan Greene – Addlestone Library’s Special Collections chief – has spent nearly a decade studying Hervey’s life and works to answer that question. His new book, The Damned Don’t Cry: They Just Disappear, broadens our understanding not only of Hervey, but of the impact of gay artists on popular culture in the first half of the 20th century. In Greene’s eyes, the book, which is the first scholarly treatment of Hervey in more than 50 years, is less a biography and more an act of literary restitution, restoring the reputation of a man who lived too soon and died too young to see justice done for himself and the causes he championed.

This Tuesday, Jan. 30, 2018, Greene will present a lecture on Hervey’s bold life as the first of three events in the spring 2018 Faculty Lecture Series “Narrating Charleston on the Margins,” which explores the myriad ways Charlestonians have identified themselves throughout the city’s history. The lecture will be held in Addlestone Library room 227 at 12:00 p.m. The series is produced by the College of Charleston Friends of the Library and the Honors College to highlight the latest in faculty research across campus. Each Faculty Lecture Series event is free and open to the public, but registration is required. To learn more about “Narrating Charleston on the Margins” visit: http://friends.library.cofc.edu/faculty-lecture-series/.

In the run-up to his lecture, The College Today posed a few questions to Greene about his research of the enigmatic Hervey.

How did you come across Hervey, and what inspired you to dig so deeply into his life and works?

How did you come across Hervey, and what inspired you to dig so deeply into his life and works?

I was curious as to who this fellow was who wrote such an unusual book about the city, Red Ending. As an archivist processing papers of other Charleston writers, I found a few references to Hervey which were so tantalizing that I started to be on the lookout for any mention of him. Any time I saw a book by him, I bought and read it. The most rewarding aspect of my research was satisfying my own curiosity, and shining a light on a completely ignored personality and part of our past.

While many today are unfamiliar with Hervey, he was an established and well-known figure during his lifetime. How would you describe his career and impact to today’s readers?

Hervey was a popular writer, who amused many. Scholars have said he influenced one work by William Faulkner and another by Graham Greene. He also wrote the scenario – not the screenplay – for the classic film Shanghai Express, which is still admired by film critics and historians. No doubt, over the years, like light traveling eons to arrive, he amused, encouraged, and winked at gay male readers who were probably fortified by finding a secret brother they never knew they had.

He impacted popular culture; people built upon his work and eclipsed it. A tree can fall in the forest and no one can hear it, but it still fell. As a biographer, maybe I delude myself into thinking that others might be inspired by the life of a person who blithely rejected society’s rules while succeeding along the standards he set for himself.

Hervey hazarded personal and professional risks by living life as an openly gay man in 1920s Charleston. What was life like for him at this time in the city?

As time has passed, people have changed their view of him. I think familiarity bred contempt. At first when they saw him with his young friend Carleton Hildreth, folks assumed they were pals out on an amazing adventure, globetrotting and writing about it. But when it was discovered they were not “innocent” friends, but “guilty” lovers, attitudes changed. If you were gay and obeyed social conventions of the day, you were OK. If you broke the rules, you were taboo.

Was it this reluctance to kowtow to convention that contributed to Hervey’s “disappearance”?

He had no descendants to make claims for him, or to try to keep his books in print. Times changed, and his most obviously gay book, The Iron Widow, was published during the Great Depression, so there were not many copies to be found. No one ever lionized him and he managed to anger and inflame the two southern towns most associated with him, Savannah and Charleston. Who back then was going to carry a torch for a scandalous scribbler? And if no one carries a torch, how can memory continue to burn and shine?

How would you characterize the differences between Hervey’s experience and those of gay authors who came after him?

Hervey’s experience is a mirror image of that of today’s gay authors. In his day, being gay was a ticket out of town and out of the literary canon. In the late 20th century, being a gay southern writer was an invitation to an exotic room with a haunted history. Today, it’s a lousy and lazy way to sum up a writer.

As a novelist yourself, how has researching Hervey inspired your own writing? And what do you think all authors – regardless of sexuality – could learn from his life and works?

Winemakers like to drink wine, and get drunk off of other vintner’s work. Writers do the same with other writers. I so enjoyed reading his books, though it has to be said his first few are forgettable. But actually, he has shamed me. He forsook respectability to write his books; I chose the middle class route of job and possessions and there are so many books I will never write because of that. Hervey spoke of being haunted by the ghosts of what he did not achieve. One consolation I have is that I have always written of people who might have been forgotten if not for some spelunking sleuth like me.

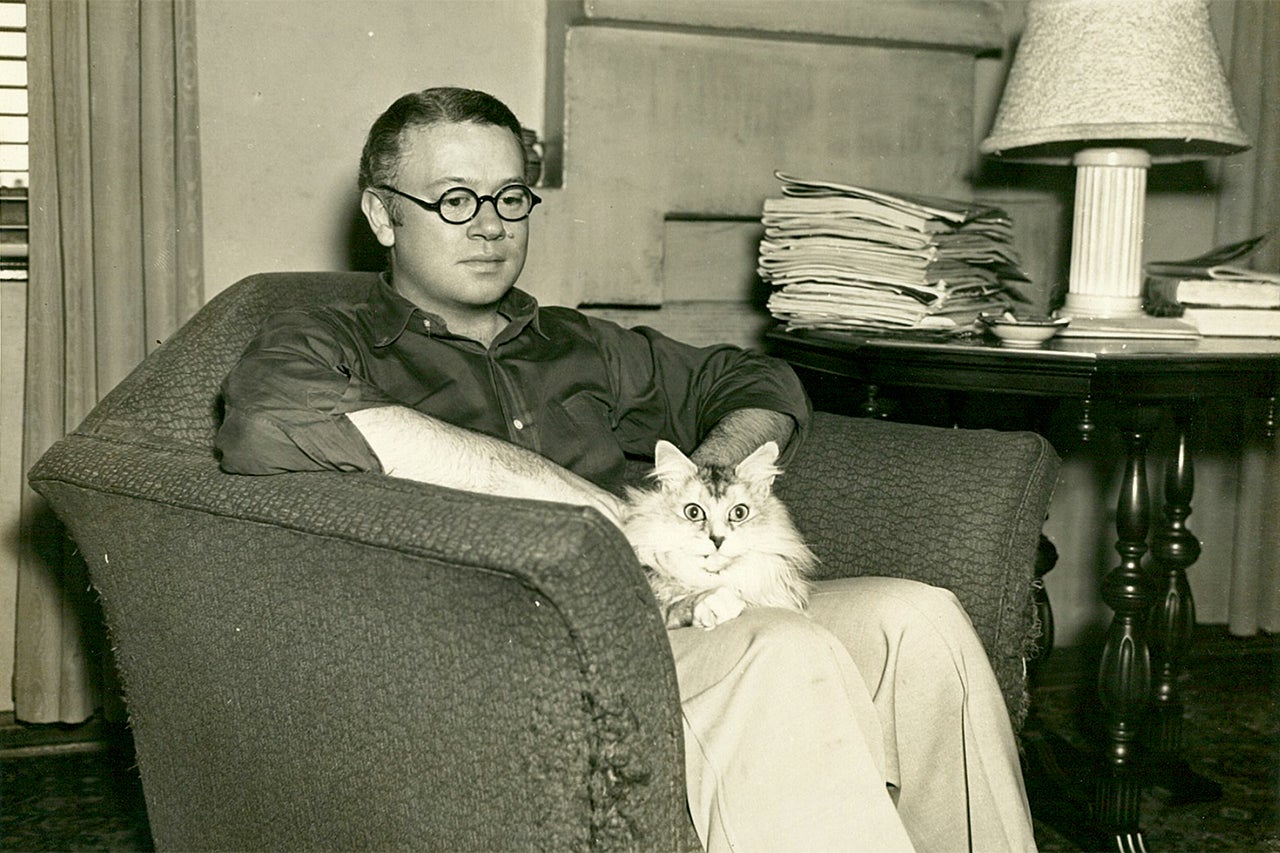

Feature image: Harry Hervey