A new discovery is changing what paleontologists thought they knew about horned dinosaurs.

In the summer of 2015, College of Charleston professor Scott Persons was looking for fossils in the badlands of southern Alberta, Canada. Hiking down a ridge, he spotted a fossil horn poking straight out of the hillside, and he began to dig around it. The horn, bigger around than a baseball bat, was not an isolated bone. It was still connected to a huge skull.

“That’s exactly how you want to find a dinosaur,” says Persons. “If much more of the skull had been exposed on the surface, it would have started to erode away and crumble. But only the tip of Hannah’s snout horn was protruding, and the skull was otherwise beautifully preserved.”

Tradition dictates that the person who finds a particularly important dinosaur specimen gets to give it a nickname. “Hannah the dinosaur is named after my dog Hannah,” says Persons. “She’s a good dog, and I knew she was home missing me while I was away on the expedition.”

Despite the chosen nickname, paleontologists have no way of knowing if the dinosaur was female.

“Large horned dinosaurs come in two basic types,” Persons explains. “There are those with big snout horns and short neck shields and those with short snout-horns and tall neck shields. It was clear from the beginning that Hannah was one of the big snout horn, short neck shield variety, but it was not clear what exact species it was.”

As the digging went on, more of the skull was uncovered. “Finally, we reached the back of the skull, and that’s when horns started popping out all over the place.”

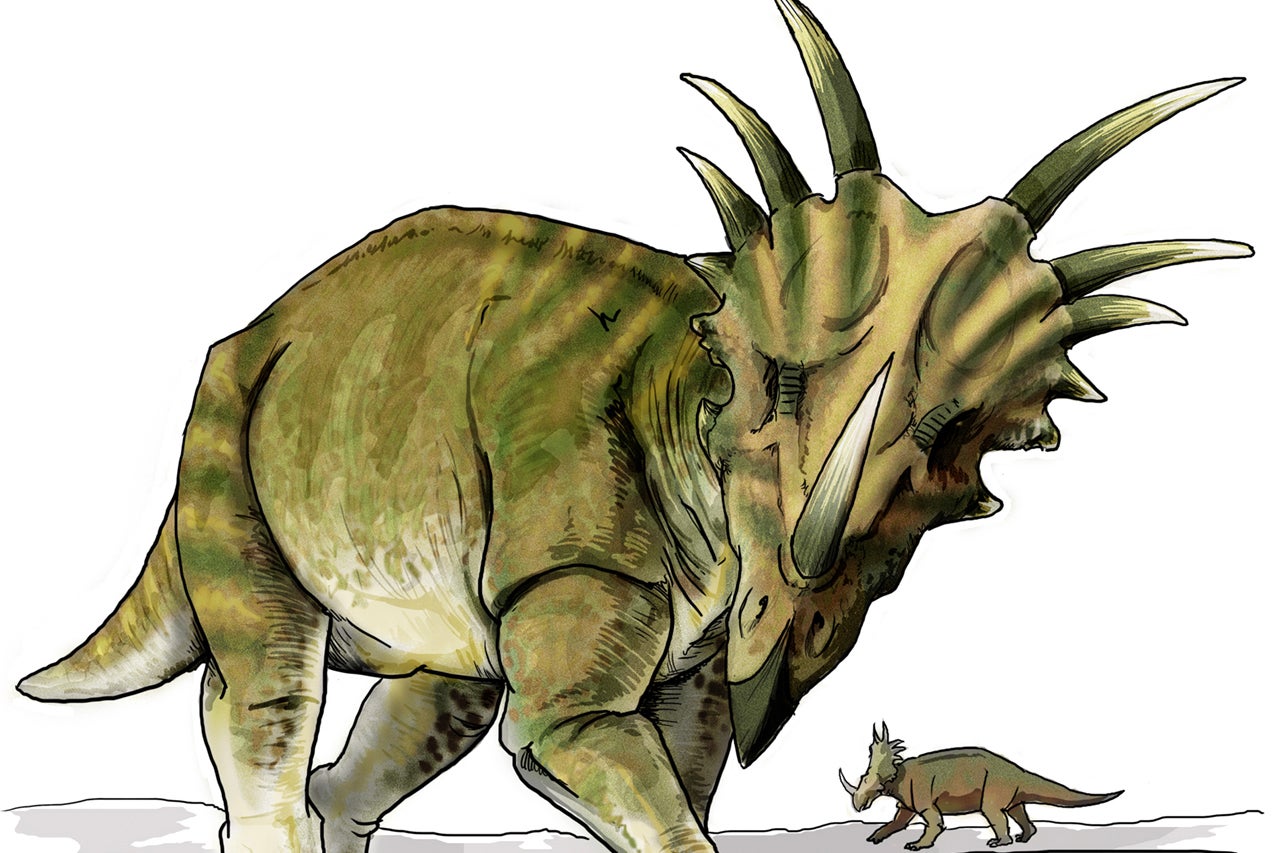

It turned out that Hannah was a Styracosaurus – a prickly beast, over five meters in body length, with a fan of long horns projecting from its expanded skull. These extra horns presented the dig team with a big challenge.

The chiseled block of sandstone that contained the skull was so big that the team could not lift it. The diggers were forced to call in a dinosaur airlift. The skull block was maneuvered into a net and then lifted and flown out of the field by a helicopter.

Four years and a lot of chiseling later, an international research team has now published a full scientific analysis of the skull. Leading the work was Robert Holmes, an expert on horned dinosaurs.

Even by the horned standards of Styracosaurus, Hannah has a lot of horns and some are much longer than in other Styracosaurus specimens. “The skull shows how much morphological variability there was in the genus,” says Robert Holmes, an expert on horned dinosaurs and member of the research team.

What’s more, Hannah’s horns are not symmetrical. The horns on Hannah’s left side are nearly all larger than those on Hannah’s right side. The researchers are still not sure why this is. Hannah’s left side also shows evidence of an injury. Thin platy bone has grown over what should have been a natural smooth opening.

“It looks like Hannah suffered from some kind of old wound or infection, or both,” says Persons. “Something happened to the left side of the face, probably when Hannah was young and the skull was still growing. It wasn’t lethal, Hannah lived through it, but afterward the skull bones grew in a strange way.”

The right and left differences are so extreme that, had the paleontologists found only isolated bits of the right and bits of the left, they might have concluded that they belong to two different species.

According to the research team’s publication in the peer reviewed scientific journal Cretaceous Research, this is one of the major lessons learned from Hannah’s skull. Like the branching prongs in the antlers of modern deer and moose, the pattern of horns in dinosaurs could be variable within a species. As a result, some of the horned dinosaur species that were once assumed unique will have to be reevaluated.