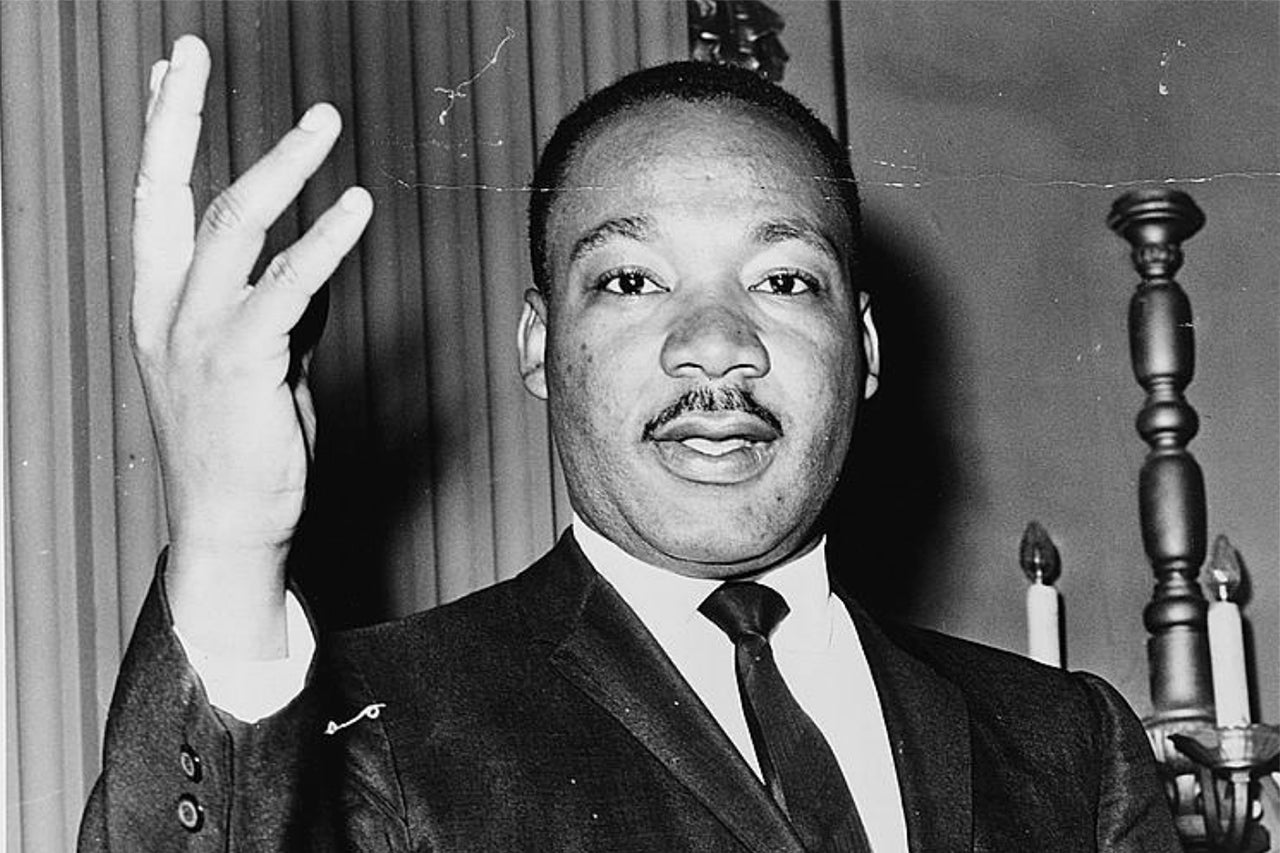

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. is an American icon and a seminal figure of the civil rights movement. But through the passage of time, details of the man and those who fought at his side have faded.

Antron Mahoney, visiting assistant professor of African American studies at the College of Charleston, says it is important to remember the context of the times, the danger King and his fellow civil rights activists faced, the complex political nature surrounding issues of civil rights, and that King was but one of many men and women who worked tirelessly to see people of color afforded equal rights.

Signed into law in 1983 by President Ronald Reagan, Martin Luther King Jr. Day was first observed in 1986. It is celebrated on the third Monday of January each year in connection with King’s birthday on Jan. 15. The College Today caught up with Mahoney ahead of this year’s MLK Day, Jan. 20, 2020, to ask about King’s place in history, his approach to seeking civil rights and his legacy today.

What key moment propelled Martin Luther King Jr. to become a central national leader in the civil rights movement?

Martin Luther King Jr. was propelled into the national spotlight when he was selected as head of the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) in 1955. Organized by E. D. Nixon, the MIA was one of the local organizations in Montgomery, Alabama, responsible for the Montgomery bus boycott. King, who was only 26 years old, was in part chosen for this role because he was new to Montgomery, and in some ways, untainted by the brash politics of city leaders. During the course of the boycott, however, King would be arrested and have his home bombed. Ultimately, the campaign ended in a victory, and city buses were desegregated – making King a nationally recognized civil rights leader.

King’s “I Have a Dream” speech is one of his most recognizable. Is it, in your opinion, his most important speech? Why or why not?

In many ways, King has been firmly archived in our national memory as a symbol of hope and progress – there are monuments, parades and a MLK Boulevard in many cities across the U.S. All deservingly so. However, one of the drawbacks of this archiving, or memorializing, is the delimitation of his legacy. King’s life and work, and by proxy the civil rights movement, are often reduced to soundbites and pinnacle moments in the movement, resulting in a lack of understanding of King’s political philosophy and the collective nature of the movement. The “I Have a Dream” speech, given at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963, is one of these moments.

Interestingly, the iconic “I Have a Dream” riff in the speech was not planned, and was prompted by gospel singer Mahalia Jackson. This anecdote about the speech can be seen as symbolic of how we have come to remember King and the civil rights movement, where those who supported, contributed or prompted the movement are often left out of the dominant narrative, particularly women such as Jo Ann Gibson, Ella Baker and Charleston’s own Septima Clark, for example.

RELATED: Learn more about Septima Clark and her birthplace, which is located on the CofC campus.

What do you think is his legacy in terms of shaping the larger American civil rights and political landscape?

The way King has been memorialized typically obscures his more structural critiques of power in society. At this point in time, I think it is beneficial to also remember the King who in 1967 spoke of “the triple evils” of racism, poverty and war and their interlocking systematic nature. I don’t believe we as a nation have begun to truly wrestle with this part of King’s legacy.

What were some of the challenges that King faced in terms of unifying and galvanizing people around his approach to achieving civil rights?

We often romanticize the civil rights era and don’t acknowledge how dangerous it was to be directly involved. In the South in the 1950s and ’60s, you could easily lose your job or even be killed if you were seen as a “troublemaker,” agitating the established white power structures. This made King’s nonviolent, direct action approach even more dangerous for those involved. Then, contrary to King’s approach, there were others who believed that political resistance should involve forms of self-defense.

How is King remembered today within the African American community?

For many African Americans, King exemplifies the best of black institutions and their justice-oriented traditions, whether it’s the black church, historically black colleges, black fraternal organizations, etc. Therefore, African Americans look to King with great pride, not simply for his individual acumen, but for all he represents – the communities in which he arose.

In general, I believe King’s legacy is about aspiring a type of love-in-action. One that fosters radical, beloved communities in efforts to restore the humanity of those who have been dehumanized by all forms of oppression and seeks justice in the face of seemly insurmountable odds.