By Jacob Steere-Williams

I’ve lost track of how long I have been in quarantine. In January 2020 I was teaching one of my favorite courses at the College, History 116: Epidemics and Revolutions, telling students about reports from virologists in Wuhan Province, China, of the emergence of a novel coronavirus, a family of viruses known to scientists from the 1960s. As we were about to embark on an entire semester of studying past pandemics, I told students that we might be seeing the beginnings of a new pandemic. Fast forward to the fall 2020 semester, and those discussions seem like an eternity ago.

As a historian of pandemics, I have been telling my students for nearly a decade to be ready for the next big pandemic. I am all too familiar with the ways that outbreaks of epidemic disease upend communities, threaten our lives and shake the very core of our existence. Pandemics, after all, are an inescapable part of being human. COVID-19 is a salient reminder of the fragility, but also the resilience of the human condition.

What have we learned from COVID-19? Some have found solace in new hobbies at home and in the outdoors. Others have found ways to connect and reconnect with family and friends through virtual book clubs and happy hours. COVID-19 has accelerated our sense of time, but also slowed down our pace of life. In my neighborhood, for example, during my twice-daily walks or bike rides with my children, I’ve met and bonded with new neighbors and made new friends. Small silver linings. The pandemic has wrought new challenges too. I think most of us can admit to never having to feel the pains of both pandemic fatigue and back-to-back-to-back Zoom fatigue. Before COVID-19, few Americans outside of infectious disease specialists regularly used the words contact tracing and case fatality, or knew the difference between isolation and quarantine.

COVID-19 has exacerbated both racial inequality and the failures of preventive public health. Just as in past pandemics, we have seen some of the worst parts of our humanity, with xenophobia raging alongside anti-science, anti-mask wearing and a general mistrust in the scientific community. Most Americans now at least realize a phrase I have on repeat in my history of epidemics class: Epidemics are inherently political events. Public health is about population management and also about citizenship, a constant wrestling match between individual and community health.

It’s easy to be pessimistic in the middle of a generation-defining natural disaster, but there are shades of optimism. Now, more than ever, we have realized the importance of community. COVID-19 won’t be the last public health crisis. How we respond today will both define us and also shape the future. We have, in other words, an opportunity: to recast the valuation of preventive medicine, to overturn structural and racial inequalities that lead to the social determinants of health, and to acknowledge and work toward a sustainable future. The environmental reasons why the novel coronavirus emerged are inextricably linked to human-induced climate change. And, like solving the problems we face with climate change, the only way we will move forward in mitigating infectious disease is with a global approach where we take responsibility for our individual actions.

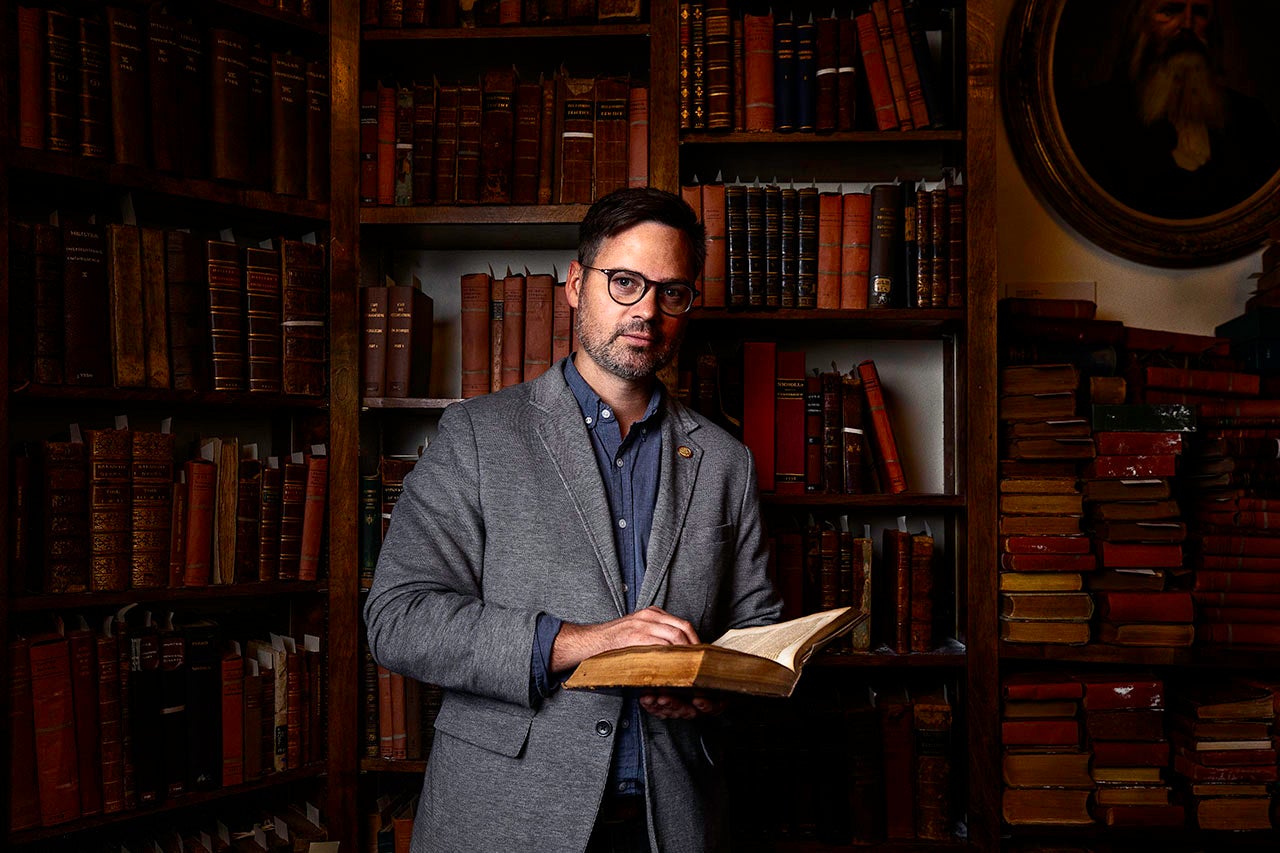

Jacob Steere-Williams is an associate professor of history and author of The Filth Disease: Typhoid Fever and the Practices of Epidemiology in Victorian England, due out in November 2020.