When College of Charleston English professor Alison Piepmeier died of brain cancer at the age of 43 in 2016, there were words she’d left unsaid and research she hadn’t yet finished. As the mother of a child with Down syndrome, Piepmeier, who was a prolific writer, had been working on a book about the nuances and challenges of raising children with Down syndrome when she ran out of time.

Before she died, Piepmeier asked her friends and colleagues, Rachel Adams, professor of English and comparative literature at Columbia University, and George Estreich, an author who teaches writing at Oregon State University, to “piece together what she did not have time to complete.” That final work is now done.

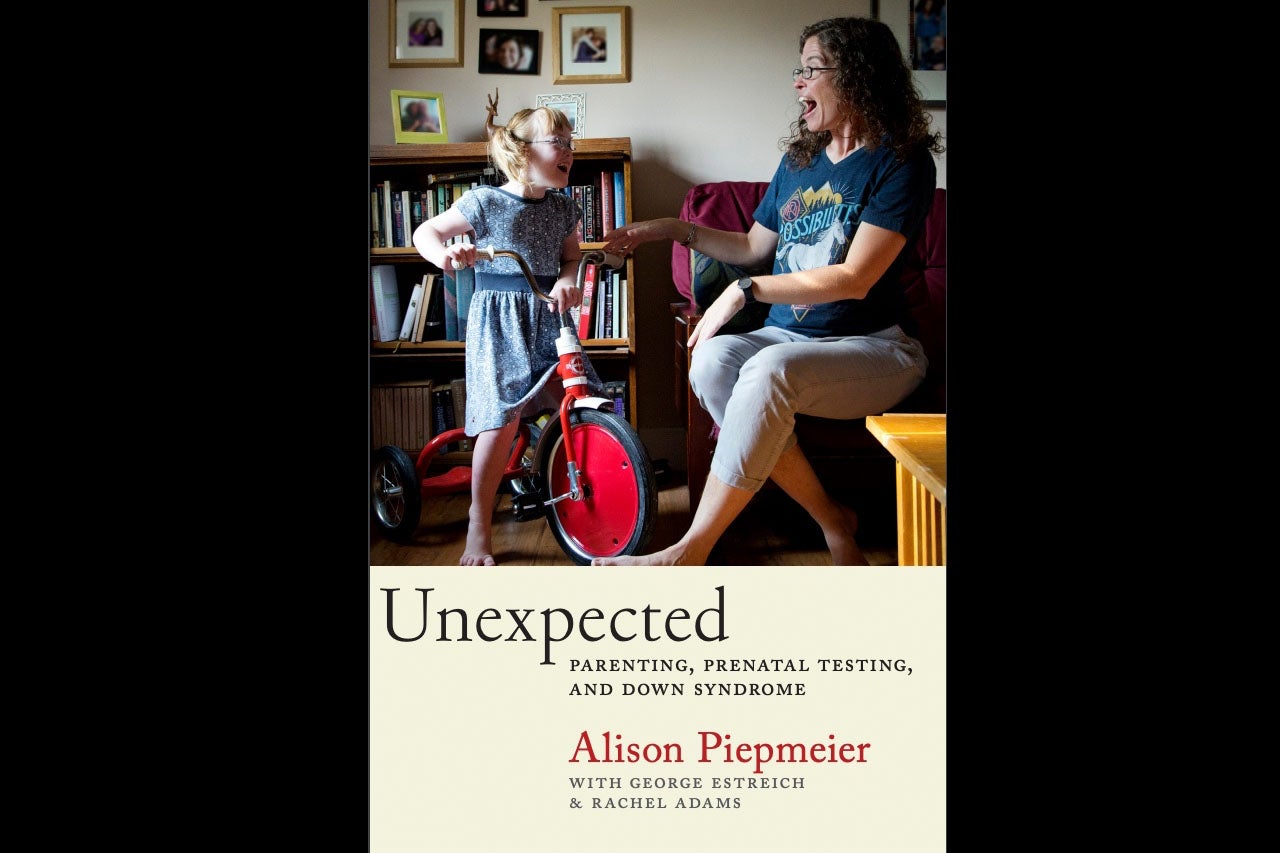

Unexpected: Parenting, Prenatal Testing, and Down Syndrome offers interviews with parents of children with Down syndrome as well as scholarly research, weaving a narrative that is both deeply personal and academic. The book is available for purchase through NYU Press.

RELATED: Read Alison Piepmeier’s final essay to the CofC community.

“The signature of Alison’s writing, either scholarly or informal, was its striking blend of complexity and accessibility,” says Estreich. “She wanted to spur conversation with as wide an audience as possible.”

Piepmeier’s research emerged from her desire to hear the stories of individuals about reproductive decision making – individuals who she said “were taking on the hard work of changing the narratives about Down syndrome.” These conversations helped Piepmeier, whose tenure at the College included founding and directing the Women’s and Gender Studies Program, navigate her journey as a parent of a child with Down syndrome and expand her definition of personhood. In the book, she asks readers to recognize people with disabilities as fully human and to challenge existing ideologies of what is and what is not “normal.”

“No one should have to pass a test to be human, to be part of a community, to be loved,” Piepmeier wrote in the book. “We all benefit from inclusion and from changing the community so that it accommodates all of us.”

Cindi May, professor of psychology and a close friend of Piepmeier, says Unexpected provides a rare and personal window into the decisions many women face when their children are diagnosed with a disability prenatally.

“Often these decisions are driven by fear, which in turn is fueled in part by misconceptions and antiquated information about disability, and in part by very real and pervasive biases against people with disabilities in our society,” says May. “Here in our own state, for example, caregivers of people with disabilities have been prioritized for the COVID vaccine over the individuals with disabilities themselves. This is despite data indicating that people with Down syndrome, for example, are at 10 times the risk of death related to COVID. We have a longstanding crisis of ableism in our society, and Alison’s book will help shine a light on the way that impacts families from the very beginning of life.”

Estreich says he and Adams approached the project as a collaborative effort.

“Our job was to make quiet, invisible repairs,” he says.

Piepmeier worked on the book throughout cancer treatments and several chapters are extended versions of essays previously published in the New York Time’s parenting blog Motherlode. Other unfinished chapters had notes to aid the editing process and in the preface, written by Estreich and Adams, they explain that their goal was to “help Alison speak with our help.” As fellow parents of children with Down syndrome, they also each contributed a chapter.

Kathleen Béres Rogers, associate professor of English and director of the College’s medical humanities program who also has a child with Down syndrome, hopes that readers take away a new perspective and appreciation for the complexities families, particularly women, face when navigating issues of reproductive rights and disability rights.

“As a member of my department, an activist and a mother of a child with Down syndrome, Alison was a mentor to me in more ways than one. Because of her, my daughter now goes to school with her daughter, and both are completely mainstreamed,” says Rogers. “Because of her, I expanded my research from literature and medicine to include disability studies, an area she taught about frequently. The thing I most respected about Alison was her ability to make complex, nuanced arguments, like those found in Unexpected. Reproductive rights and disability rights often clash, and Alison unpacks this tension with care and profound empathy.”

And Piepmeier, through her book, will leave a lasting impact on the field of women’s and gender studies for years to come.

“The imprint that Alison left on the Women’s and Gender Studies Program, in feminist research and activism, and on everyone who encountered her is enduring,” says Kris De Welde, the current director of the College’s Women’s and Gender Studies Program. “The importance of this work to the field of women’s and gender studies can’t be overstated. It is nuanced, complex, emotive and provocative, much like all of her scholarly contributions. We are fortunate to have had Estreich and Adams take up this project and bring it to fruition as part of Alison’s far-reaching legacy.”