Long before the College taught its first class in 1790, it boasted an impressive collection of books upon which to build its library. But this inaugural donation of 800 volumes – at the time rare and expensive objects – was nearly lost before the College began to function in earnest.

In the early morning of January 15, 1778, a fire sparked on the Charleston peninsula that, in the span of eight hours, razed more than 250 structures. The flames did not spare the Charleston Library Society, the city’s preeminent cultural institution tasked with safeguarding the books for the College.

Fortunately for future Cougars, 66 books of that original donation were rescued from the smoldering heap and transferred to the College nearly 200 years later. Today, they are preserved and publicly available in the Libraries’ Special Collections.

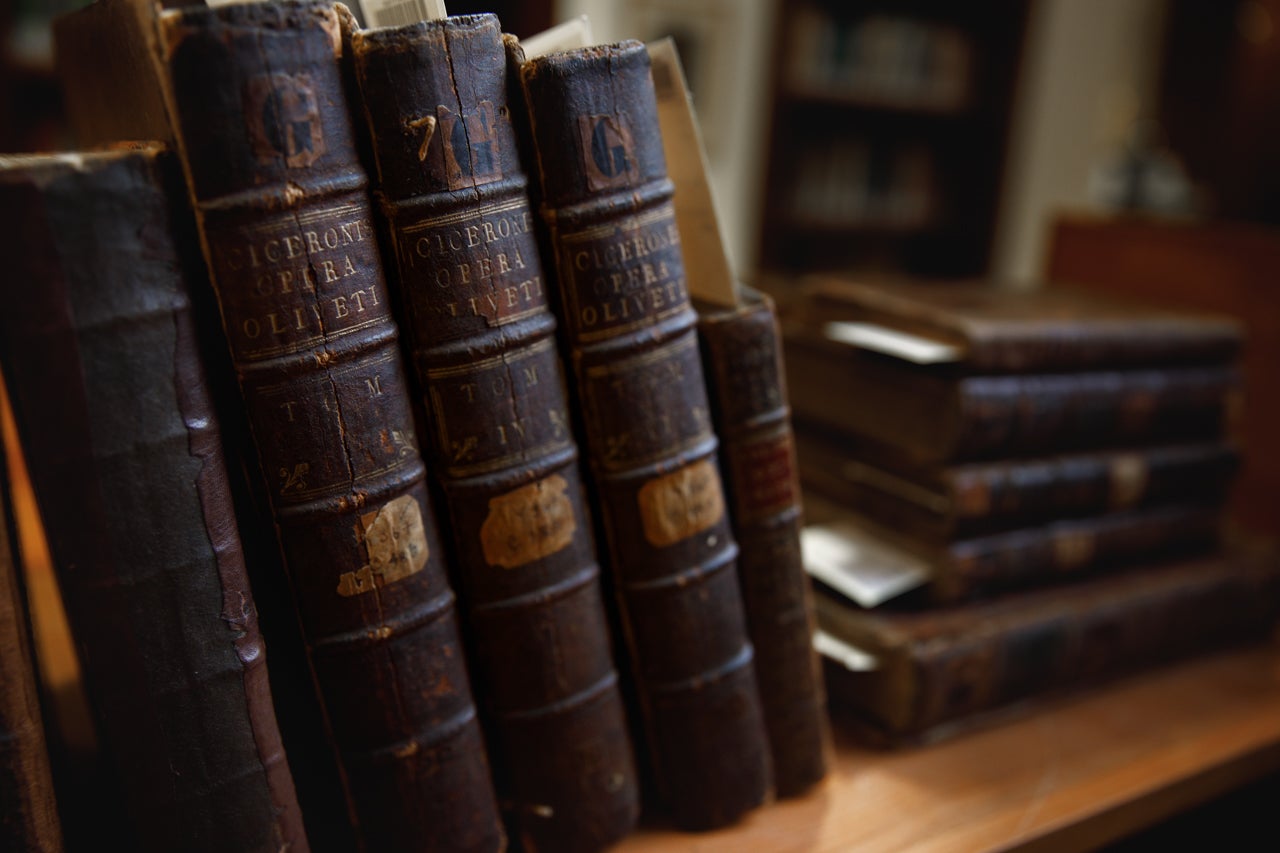

The books’ narrow escape from oblivion left scars still visible all these years later: charred spines, singed papers and ashen blotches. But to open one up, the gilt lettering remains legible and their original owner made clear: John Mackenzie, Esq.

John Mackenzie’s collection survived a fire in 1778. Photo by Heather Moran.

An elusive and contradictory figure, Mackenzie was a devout patriot, who – incensed by the British Crown’s Townshend Acts – served as an early advocate for independence. His collection of books appeared in an early survey of all private libraries in colonial South Carolina; only one commanded a higher appraisal than Mackenzie’s. He nevertheless displayed the bigotries inherent to men of his social station in the Lowcountry. Mackenzie’s wealth derived from nearly 7,000 acres of rice and indigo and the forced labor of enslaved persons on his Goose Creek plantations.

“During his lifetime, cut short in 1771 at the age of 33, Mackenzie managed to accumulate financial debt at the expense of his devotion to book collecting,” says Mary Jo Fairchild, manager of research services for Special Collections. “We know from his will that Mackenzie directed the executors of his estate to satisfy these debts with money generated from the sale of the people he enslaved, real estate and personal belongings.”

As the College-produced documentary If These Walls Could Talk demonstrates, CofC’s ties to slavery stretch back to its founding. The College Libraries’ original collection shares in this ignominious origin. But the assortment of Mackenzie’s books now serves as the foundation for a library system whose resources and services seek to benefit all patrons, with no regard to race, class or creed.

While Cougars today think automatically of the Marlene and Nathan Addlestone Library as their go-to HQ, the College’s library has had several homes throughout its history.

Originally located in Randolph Hall, the burgeoning collection of printed materials and manuscripts soon required a more capacious building.

Students in Towell Library in the mid-1900s.

What became known as Towell Library served this role for more than a century, from 1856 until the dedication of the Robert Scott Small Library in 1970 on Cougar Mall.

With the explosive growth of the College following its designation as a public, desegregated university, even the purpose-built Robert Scott Small Library began to groan under the weight of its holdings. In 2005, the Addlestone Library became the fourth and current home of the College Libraries.

The College and its libraries have grown in tandem. As in the past, changes in the information landscape require of the libraries another transformation to best serve its students and faculty.

To meet this charge of fostering digital citizenship and a makerspace culture for an increasingly media-and data-driven economy, the libraries are setting their sights on creating a nucleus for media production, experiential learning and creative cooperation.

This plan, the 21st Century Library initiative, involves the complete renovation of Addlestone’s first floor, with facilities for video production, podcasts and more, paired with the technology and instruction for students and faculty to learn, discover and create.

“These technologies offer new collaborative experiences, transporting students beyond Addlestone’s four walls and fostering their creativity and expression,” says John W. White, dean of libraries. “By embracing these changes and empowering our patrons to experiment, the libraries will continue to serve as the campus hub for discovery as they have for two and a half centuries.”