The phrases “global warming” and “climate change” have become frequent flashpoints in the media and among the lexicon of those attuned to issues surrounding the environment. But what do those things really mean? How did we get here? And what comes next?

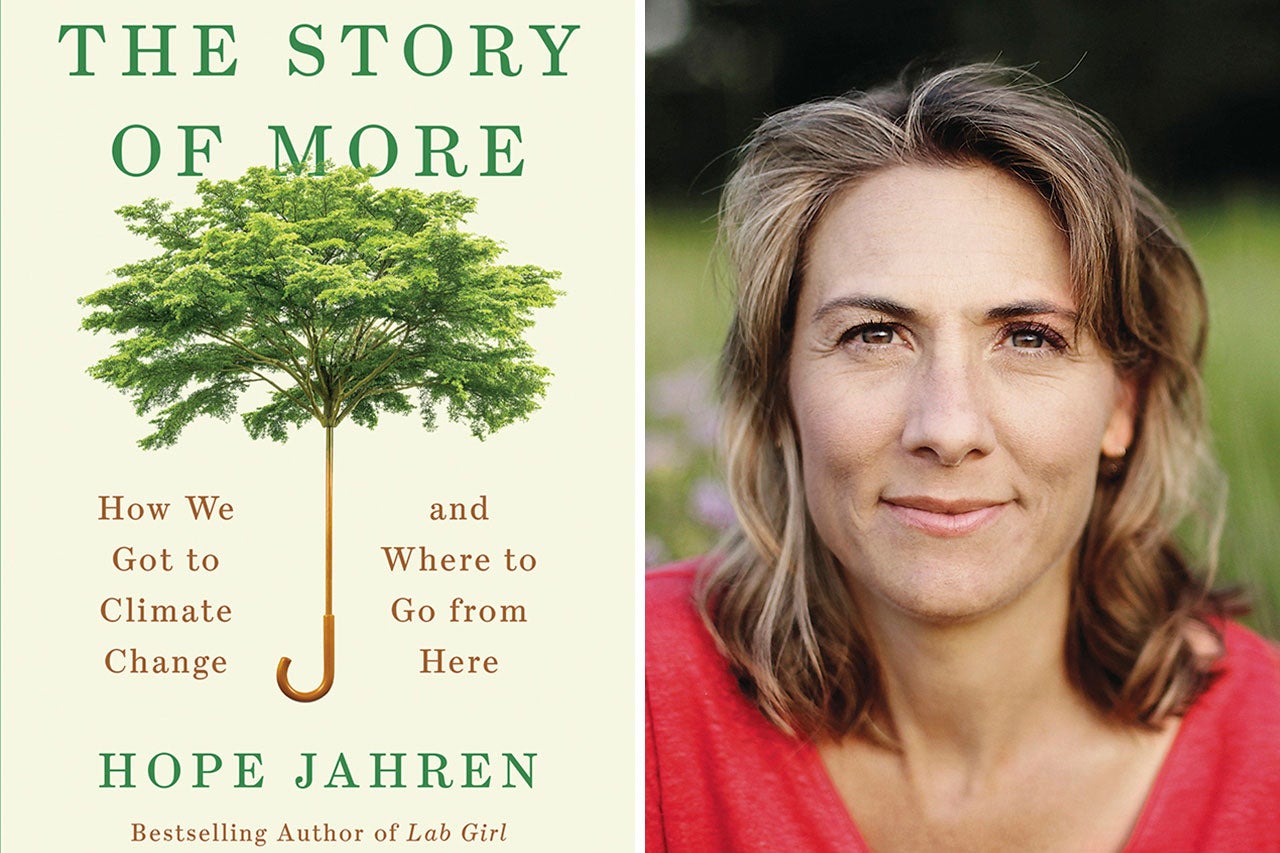

Those are the questions author Hope Jahren probes in her book The Story of More: How We got to Climate Change & Where to go from Here, which is the College of Charleston’s 2021 The College Reads! book. The College Reads! is a campus-wide common reading program designed to connect students, faculty and staff around a single book.

As part of “The College Reads!” program, CofC will present a virtual evening with Jahren, who uses The Story of More to explain the consequences of global warming from superstorms to rising sea levels and the actions that we all can take to fight back. The livestreamed talk, which is free and open to students, faculty, staff and the community, can be viewed in the Sottile Theatre and online on Monday, Oct. 25, 2021, at 7 p.m. A Q&A will follow. Please visit The College Reads! website to access the link to watch the event online.

As part of Convocation and The College Reads! Program, incoming students created art work inspired by ‘The Story of More,’ which is on display in the Stern Student Center.

Jahren, who will also meet with select CofC classes on Tuesday, Oct. 26, is an award-winning scientist, professor and bestselling author of Lab Girl. She is the recipient of three Fulbright Awards and is one of four scientists, and the only woman, to have been awarded both of the Young Investigator Medals given within the Earth Sciences. She currently holds the J. Tuzo Wilson professorship at the University of Oslo, Norway.

Ahead of her virtual presentation, Jahren sat down with The College Today to talk about what she learned from her research into global warming and what she hopes readers take away from The Story of More.

How did you find your voice for this book? What methods did you use to make scientific information accessible to a larger audience?

I wanted to write something different from what’s already out there. Let’s face it, there’s easily a hundred good books about global climate change for an interested reader to choose from, books that do a really good job of delivering information … but I like books that – first and foremost – tell a story. It turns out that the last 50 years of data on population, food production, energy use and climate alteration best fits the form of a story: one that starts about a half century ago, with a lot of rising action taking place in the 1970s and 80s, and a kind of climaxing at about 2000; it’s been falling action since then. If we are smart, we’ll use this next decade to resolve the action, to decide our own ending and not let the story simply keep writing itself. Global climate change is not an arbitrary set of events and it shouldn’t be communicated as such. It’s not best represented by a sermon or a lecture, either. It is a story — it is our story — the story of our lives.

What was your research process for writing The Story of More?

I didn’t set out to write a book, I just wanted to form my own opinion about how the earth was changing. For years, I followed my own curiosity and trusted that it would lead me to some type of understanding. Here’s an example: while traveling in the midwest, I saw that a lot of the gas stations were advertising ethanol-enriched fuel at the pump, and that the logo included an ear of corn. I wondered how you make ethanol from corn, so I went to the library and looked up the chemistry. I wondered how many gallons of the stuff they were selling, so I estimated it from the financial disclosures of the company. I wondered how much corn the company had used so I calculated it from the chemistry. Then I looked up the total corn harvest for the county, state and country. I made the calculation for different companies located in different states. Then I compared those numbers to the numbers for the years before, and before that, going back 50 years. I basically gave myself permission to stop for a minute, note down, and then go look up every little thing that caught my eye about the way I saw food and fuel used all around me, and I didn’t stop until I understood whatever it was with both words and numbers. I kept at it for 10 years and, as we all do, I told the people in my life what I was thinking about as I went. I made note of when their eyes lit up, and also when their eyes glazed over, and began to understand what parts were interesting to them. Slowly, with a lot of back-and-forth, and calculating and re-calculating and double-triple-checking, all this knowledge formed itself into a story that I could tell confidently, secure in the feeling that I was saying something important and interesting; then I wrote it all down.

What scares you the most about climate change? How do you continue to have hope?

My biggest fear is that people have absorbed the message that only the actions of big corporations and big governments matter when it comes to global change, and that there is nothing they personally can contribute to slowing, stopping and reversing climate change. It’s patently untrue and, I believe, we will never change our institutions if we cannot change ourselves. For my part, I get a lot of hope by looking at the numbers around global change, by “doing the math,” so to speak. After I got a handle on the true scope of things, of just how much we need to change the way we do things — in our factories and workplaces, yes — but also in our homes — in order to take a more sustainable approach to energy use, I began to feel much more empowered to start moving in the right direction, to change my life and begin making different choices. As with so many things, growing in knowledge serves to drive out fear.

What’s the best way to share this information with younger readers?

In November, a young-adult version of The Story of More will be released. I personally re-wrote the young-adult version in order to reach tweens and teens, mostly by switching the focus to the last 10-20 years, which is the life-span of young readers. I also shortened the text and simplified the language, hopefully making the book useful within more and different classrooms. I’ve made connections with science teachers all over the U.S. in order to learn about what they want in a book and what their students want to learn. I can’t wait to follow up and see if the book is useful and do my part to encourage students to read and think and care.

What are you working on next?

Like many scientists, I am busy evaluating the effect that all the lifestyle changes we adopted in response to COVID-19 may have had on the natural environment. It will take years to see the full picture, as the potential effects of all the driving, shopping, flying (et cetera!) that we didn’t do won’t necessarily show up in the chemistry and biology of the earth’s ecosystems right away. Nevertheless, the year 2020 was like none that came before it, and it taught us many things about ourselves. For the first time in at least a generation, we slowed to a stop, we let go and we lived without. This makes us a people who can do so when we have to. Whether it makes us a people who can commit to doing as much as it takes to slow, halt or reverse climate change is a more difficult question, and my job is to help do the science that will help us find an answer.