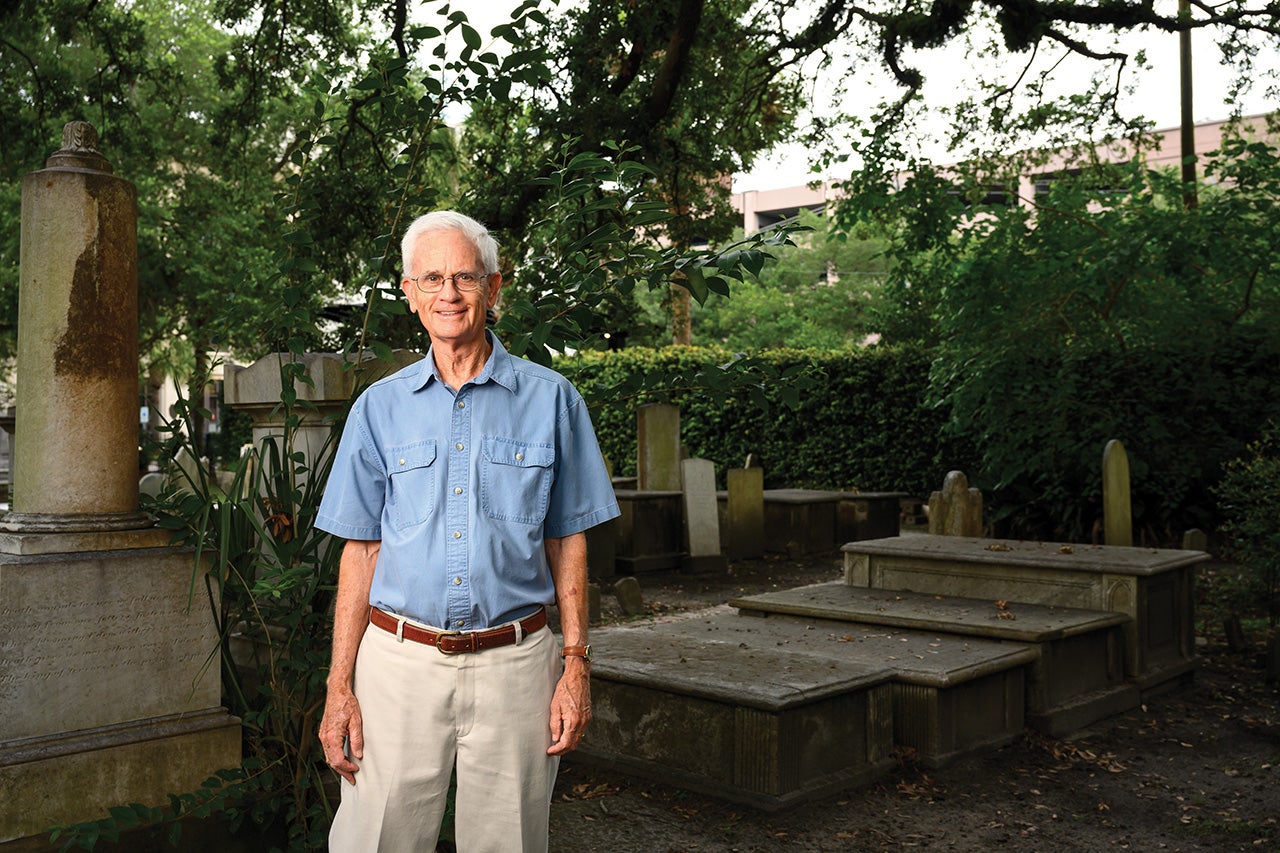

At 82, George Dickinson is the oldest professor at the College of Charleston, so it’s only fitting that the sociology professor is also the College’s leading authority on death and dying. Anyone who spends time with him becomes captivated by his passion and enthusiasm, which may explain why alumni voted him one of the Top 10 favorite professors of all time in a 2021 survey.

“Death is a part of the life cycle; it is inevitable,” says Dickinson. “In the United States, we tend to have a death-denying attitude, rather than accepting. The significance of studying dying and death is that it can help us to understand and accept the ‘normalcy’ of the process.”

Dickinson’s road to his specialty simply unfolded before him. His plans to study medicine ended quickly when he passed out his freshman year in anticipation of the brain surgery his class came to observe. He woke up to a nun in a white habit hovering over him and thought he had died and gone to heaven.

After graduating from Baylor University in 1962 with a bachelor’s in biology and a minor in sociology, Dickinson stayed on to study business. “It wasn’t my cup of tea,” he says. “Fortunately, I ran into the chair of sociology, who gave me a graduate fellowship. We still keep in touch today.”

Dickinson went on to earn his master’s from Baylor and his doctorate from Louisiana State University, both in sociology.

“I had never considered teaching,” adds Dickinson, whose mother was a K-12 substitute teacher and whose brother is a history professor. “I serendipitously fell into what I do.”

Something sparked inside Dickinson in the mid-1970s, when he met a third-year medical student who had never taken classes on death and dying. He went on to conduct a survey of what medical schools were doing about the topic and discovered that only seven of the 113 medical schools surveyed had a program. That’s when he realized a serious gap in education needed to be filled.

By the time Dickinson came to the College of Charleston in 1985, he’d already taught about death and dying at universities in Minnesota and Kentucky. That same year, he co-wrote the textbook Understanding Dying, Death and Bereavement, now in its ninth edition. Since then, he has authored three more textbooks and more than 100 articles.

Dickinson’s expertise has opened a lot of doors and opportunities. He has traveled the world and expanded his scope of work to include euthanasia and veterinary euthanasia. On his bucket list, he would like to use an fMRI to see what part of an animal’s brain registers the death of another animal being euthanized at the moment of death — he thinks it’s likely the olfactory lobes.

While continuous learning has appeal, it’s his students who drive Dickinson.

“I often have students with illnesses or who have family members who are dying or are dead,” he says. “The exposure to the subject matter helps them tackle the issue. I received a note recently from an alum from the 1980s who said how helpful the course was in coping with the death of his dad. I get letters like that quite often. That is what keeps me going.”

As long as he is able, Dickinson will continue to teach: “As my mother often said, I don’t like to let any grass grow under my feet.”

Photo by Heather Moran