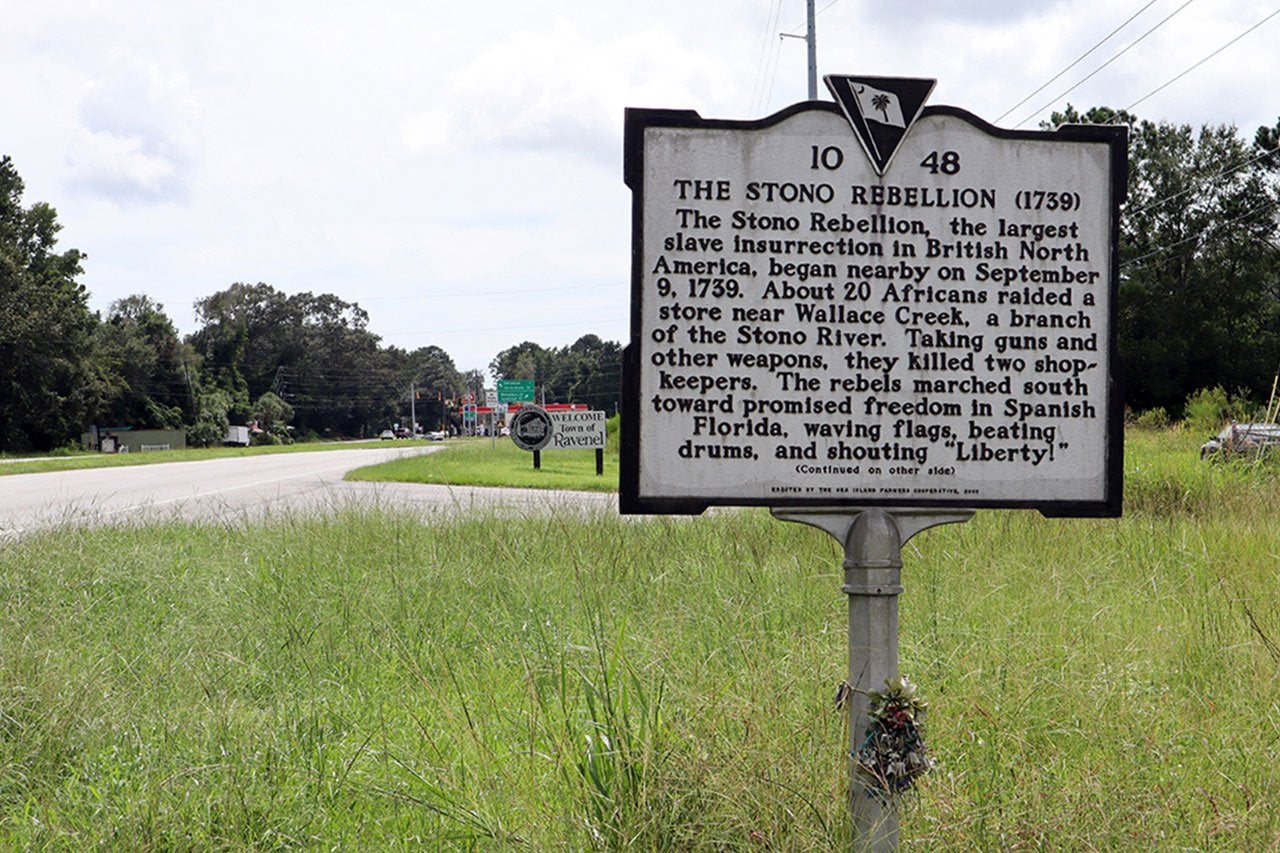

Two powerful historical events that indicate the desire of enslaved Black people to seek freedom rather than sit idly by prior to the Civil War are the 1822 uprising in Charleston organized by Denmark Vesey and the Stono Rebellion of 1739 in southern Charleston County. The City of Charleston just marked the bicentenary of the uprising and Vesey’s death with a series of events in mid-July. Now, the Stono Rebellion will be the focus of a conference at the College of Charleston Sept. 8–10, 2022.

Conducted in conjunction with the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Program and CofC’s Carolina Lowcountry and Atlantic World Program (CLAW), the 7th national Slave Dwelling Project Conference offers an in-depth look at the 1739 rebellion by enslaved African Americans along the Stono River in South Carolina and elsewhere in the Lowcountry. Conference events will take place at the Stern Student Center on the College of Charleston campus.

With keynote addresses by Edda Fields-Black, author of the forthcoming ‘Combee’: Harriet Tubman, the Combahee River Raid, and Black Freedom During the Civil War, and Hilary Green, author of Educational Reconstruction: African American Schools in the Urban South, 1865-1890, as well as many other notable scholars and historians, the conference offers the opportunity to participate in over 20 informative sessions with virtual conference attendance options as well.

With keynote addresses by Edda Fields-Black, author of the forthcoming ‘Combee’: Harriet Tubman, the Combahee River Raid, and Black Freedom During the Civil War, and Hilary Green, author of Educational Reconstruction: African American Schools in the Urban South, 1865-1890, as well as many other notable scholars and historians, the conference offers the opportunity to participate in over 20 informative sessions with virtual conference attendance options as well.

Sandra Slater, associate professor of history and director of CLAW, will deliver the opening introduction on Sept. 8 from 9 to 10:30 a.m. She spoke with The College Today ahead of the conference about the historical importance of the rebellion and what it symbolizes.

Why was the Stono Rebellion selected as the theme of this year’s conference?

This year the Caw Caw Interpretive Center was selected as a new listing on the National Park Service’s National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom. The Stono Rebellion occurred on Sept. 9, 1739, on the site of Caw Caw rice plantations, which is recognized as the central location for studying the Stono Rebellion. This conference is also in anticipation of the opening of the International African American Museum in December 2022. It emerged from a collective of scholars, public historians and cultural organizations striving to develop a month of public programming surrounding South Carolina’s Stono Rebellion (as well as other issues of self-liberation and resistance) and its impact on antislavery and civil rights activism and its contemporary relevance.

What was the Stono Rebellion?

In September 1739, dozens of enslaved people, united under the leadership of Jemmy, a man likely from the Kingdom of the Congo, resisted bondage and launched a revolt along the Stono River in South Carolina. An additional leader often identified in oral traditions as Cato worked alongside Jemmy and others. Armed with guns and ammunition they’d seized from nearby Hutchinson’s Store, they headed toward Spanish Florida where freedom awaited. Near the Edisto River, the group encountered a white militia that attacked the rebels and murdered many during the skirmishes. Some survivors escaped while planters and local authorities re-enslaved others. Militia members executed and subsequently beheaded a number of those who surrendered. The large revolt resulted in the loss of 35-50 Black and 25 white lives.

So, the Underground Railroad didn’t just run north?

The destination of Spanish Florida — long regarded as a haven for enslaved freedom seekers — complicates conventional narratives focused on the “free” northern United States and Canada. The presence of Spanish Florida within the larger narrative draws much-needed attention to the plight of the hundreds of enslaved persons in North America who fled bondage by heading south, not north — an example of the complex system of mobility and cultural variations that marked the larger African diaspora in Europe, North America and the Caribbean. Many enslaved persons who fled south evaded recapture by taking refuge in the prohibitive terrain of Florida’s wetlands. Collectively, the greater Caribbean laid the foundations for enslaved revolts and self-liberation throughout the western hemisphere, including such events as the Yamasee War (1715-1717) in South Carolina and rebellions in Jamaica, St. John and Antigua in the 1730s. Information about these and other revolts spread quickly to African Americans held in bondage in the American colonies and subsequent United States, and engendered fear amongst slaveholders throughout the Atlantic World.

What was its impact on future enslaved generations?

In the aftermath of what became known as the Stono Rebellion, the South Carolina Assembly passed the Negro Act of 1740, the first piece of legislation to actively prevent literacy among the enslaved. The act reflected slaveholders’ anxieties about the dissemination of knowledge. In addition to limiting enslaved people’s access to education, the Negro Act of 1740 also limited access to community, independent labor and the ability to cultivate private gardens. The Charlestown Assembly recognized that excessive violence and brutality in the fields had likely provoked the armed resistance later known as the Stono Rebellion, but they chose to commit themselves to greater efforts to control Black bodies rather than alleviate the miseries within slavery.

What has it come to symbolize?

Today, the rebellion serves as a reminder not only of the desperation and violence of enslavement, but also of the resilience and resourcefulness of the enslaved – whose passionate desire for liberty led them to pursue freedom at all costs. This historic moment in American history encapsulates the larger experiences of enslavement and exemplifies the resistance, rebellion, revolution and resilience that are a powerful part of the untold story of American slavery. This rebellion, only one of many, characterizes the spirit of determination that would lead African Americans to repeatedly assert their right to freedom throughout centuries of enslavement.