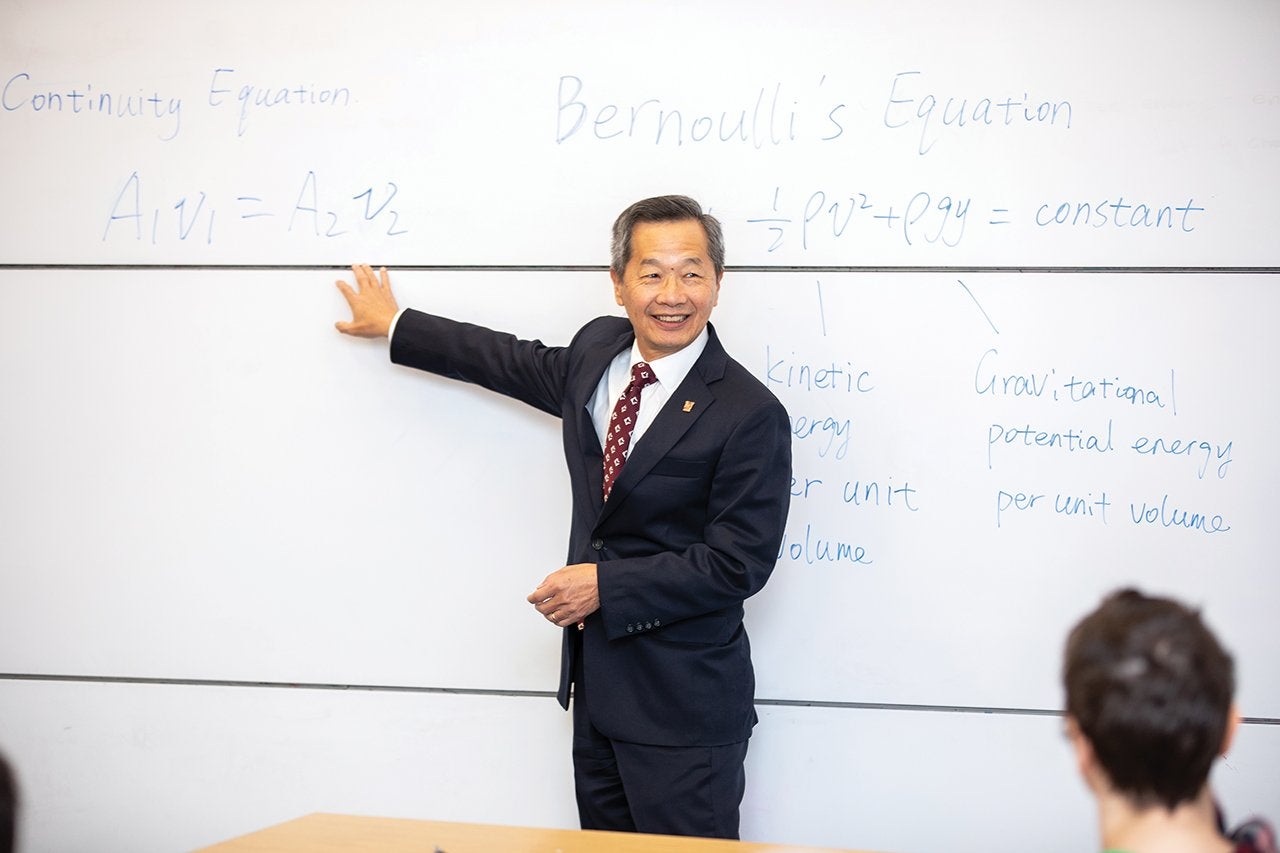

This past fall, I had the opportunity to team-teach a First Year Experience class on the fundamentals of engineering with Qian Zhang, new associate professor of systems engineering. It was a very rewarding experience to be back in the lecture hall talking about a subject that still deeply fascinates me.

The classroom is where I fell in love with higher education, and this course gave me a chance to rekindle that passion for learning and teaching. As you might expect, for many professors who move into administrative and leadership roles, it is much too easy for them to forget some of the day-to-day realities of the modern-day classroom, especially one that meets at 8 a.m. twice a week! Our upperclassmen – and alumni, for that matter – can attest to early-morning classes being the realm mostly inhabited by first-years, those students who have not yet mastered the art of scheduling their coursework later in the day.

Regardless of the decade, attendance and attention can be twin adversaries to student success in an early-morning class. Throughout the fall, I was constantly reminded of the unique circadian rhythms of teenagers and how their brain function is optimal later in the day. I know that lesson all too well with my own daughters.

Sometimes, in the classroom, I would pose a question, only to be met by a wall of silence and a crowd of blank, zombie-like stares. Fortunately, that did not occur often, and the students – sipping their caffè mochas or blond vanilla lattes or brightly colored energy drinks – did their best to wake up and engage in the day’s lesson.

It was reassuring to have students excited about learning and seeing their enthusiasm firsthand. For me, the beauty of engineering is that most things in this world follow some basic rules – or laws, if you are Sir Isaac Newton – that are fairly simple and straightforward but can then be used to calculate some really complex, real-world concepts.

For example, in one lesson, we focused on Bernoulli’s equation, named for Swiss physicist Daniel Bernoulli and used to relate pressure and speed in fluid dynamics. It’s a foundational concept that all engineers need to understand. In a previous class, I had asked the students to collect some basic data, specifically on the cross-section of area and speed of the water coming out of their home faucets. From that information, we were able to prove the continuity equation and the conservation of momentum (or Newton’s second law of motion). So, from the dorm-room faucet, we moved to the aerofoil of a modern-day jet to talk about the lift and drag on a plane’s wing.

And that’s why I appreciate scientific thinking so much: that these simple “rules” can be applied to something greater and even theoretical. The ability to go from the basic to the complex has defined humanity’s genius for millennia, and that type of thinking serves as the core of our liberal arts education, whether you are studying philosophy, art history or economics. So much so that it is, in my humble opinion, like having wisdom on tap.

– President Andrew T. Hsu