Memory is a funny thing. It knows what you wore on your first day of Kindergarten, but not where you left your keys. It mulls over obscure details of a research study while you’re washing your hair, but – heaven forbid someone ask you what it was about: blank stare.

Some things do stick with us, though. Some things are always there: relics that just stand out. And the students in Nathaniel Walker’s Architecture of Memory course were charged with designing something that will stick around forever: a memorial to the victims of the slave trade to be installed outside the International African American Museum on the Charleston Harbor.

Nathaniel Walker, assistant professor of art history at the College of Charleston, specializes in architectural and urban history.

While there’s only a small chance any of the students’ design proposals, which are based on their historical research in the course, will actually be installed at the museum, all 10 of them will be on public display this summer.

Hush Harbor: An Exhibition of Student Designs for a Monument to the Courage of Those Who Suffered During the Atlantic Slave Trade is opening in the third-floor hallway of the Albert Simons Center for the Arts on Wednesday, May 6, 2105, at 7 p.m.

“The course surveyed museums, monuments and memorials and looked at how the public spaces of cities are deliberately invested with memory,” says Walker, professor of architectural and urban history in the College’s art history department, noting that the course had a special focus on Charleston’s objects of memory.

“Charleston is a city of memory. We have this rich landscape of memory here,” he says. “There are so many monuments and so many memorials, our ancestors are competing for our attention, our faith, our memory.”

And among those many memories, of course, are slavery and African American history.

In December, Walker met with Mayor Joe Riley, who accepted his idea to have his class propose designs for a memorial outside of the museum. The students attended meetings of the IAAM and of the Board of Architectural Review, gathering input to inform their designs.

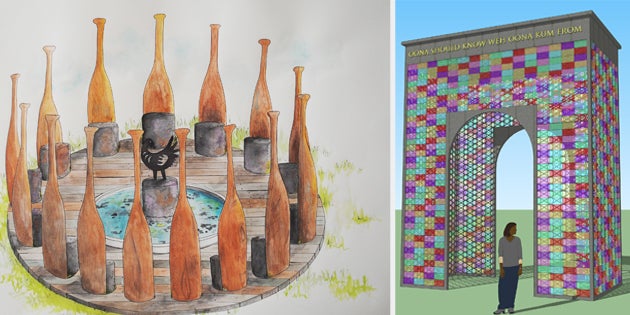

Masters candidate Kelly Hogan’s design proposal for a memorial to Charleston’s slave trade victims. For the final project for the College’s Architecture of Memory course, students were required to create a design proposal for a memorial to be installed outside Charleston’s future International African American Museum. All 10 design proposals will be featured in the “Hush Harbor” exhibit opening May 6 in the Simons Center for the Arts.

“After hearing the community voice their concerns, I decided to come up with my own design that would represent the Charleston community within the IAAM’s international narrative,” says Kelly Hogan, a master of arts in history candidate. “One of the major concerns within the community was that their stories would be ignored, and that they would be robbed of their agency.”

Hogan’s design of a wrought-iron arch with glass bricks overlaying it, allows and encourages the community to select and purchase a brick to place in the arch, thus representing building up from the past as an ongoing social endeavor.

“The colorful bricks also represent this beautiful progressive narrative that’s been told since the conclusion of the civil rights movement; however, the scars of the past (the wrought iron) are still very much visible through this narrative,” says Hogan. “I also wanted to design an arch that would speak to the triumphal arch in Benin, The Door of No Return, which acts as a gateway for the souls of the slaves to return home back to Africa; I wanted an arch to answer this, allowing the souls to transverse between America and Africa.”

Working in groups, the students had to be both reasonable and ambitious in their designs, showing creativity and also the historical knowledge they’d gained throughout the semester – thus requiring a broad skill set.

“The exposure this class provided me to the museum design and exhibition process has cemented my desire to pursue a career in museum work,” says Elaina Gyure, a senior history major.

“I learned how to deeply research, analyze and formulate a memorial in order to show the group who I am memorializing the utmost respect,” says Madeline Ryan, a sophomore arts management major.

And that is enough for Walker, who is quite proud of his students, even if none of their design proposals do end up outside the IAAM.

“I was impressed with the complexity they showed in their social reflection present in their designs,” says Walker. “It’s very tricky to make people feel empowered, and not like victims, when recognizing the calamity of the past. They were really, really, really careful about this balance – the need to celebrate the strength of African American history while also being honest about this country’s mistakes.”

And, maybe – just maybe – one of the designs will stick around not just in memory, but in Charleston’s memorial landscape, as well. In any case, Hush Harbor will be on display through September 1.