Sometimes things just come together.

Such was the case with the discovery of a 28-million-year-old fossil belonging to a previously unknown toothed whale. It was a find that, once carefully assembled, connected not only some evolutionary dots for the scientific community, but also some like-minded personalities in the College community.

The discovery began in the early ’90s, when Mark Havenstein ’88 – co-owner of Lowcountry Geologic, an online fossil store specializing in megalodon shark teeth from the South Carolina Lowcountry – came across the fossil in Berkeley County.

Things started falling into place almost immediately.

First, Mace Brown, an avid private fossil collector, bought the fossil from Lowcountry Geologic. As he began preparing it, he could tell from the strange indentations in the whale’s skull, that this was an unusual find.

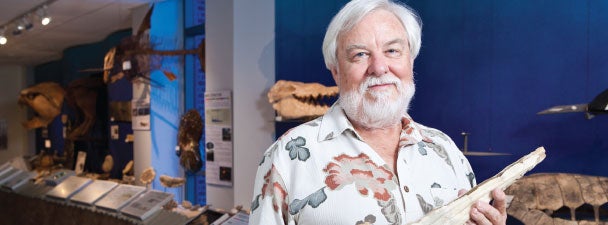

That’s when he called in geology professor Jim Carew and Jonathan Geisler ’95 to take a look at the specimen. Geisler– who, like Havenstein, had taken Carew’s paleobiology class while at the College – had earned a master’s and a Ph.D. from Columbia University and served as curator of paleontology at Georgia Southern Museum. Now an associate professor of anatomy at New York Institute of Technology, he agreed it was an extraordinary find, but he couldn’t perform professional research until the specimen was in a museum. Carew’s shared interest, too, was restricted by the fossil’s place in Brown’s personal collection.

“To do scientific research,” Geisler observes, “you need the specimen to be in a museum where other researchers can see it and decide whether or not they agree with your findings.”

Thus, Carew worked with Brown to open the Mace Brown Museum of Natural History in the College’s School of Sciences and Mathematics Building in September 2010. This and many other of Brown’s specimens were donated in 2013.

In the meantime, Carew and Geisler discovered that the fossil was a previously unknown whale species. They also realized that its skull structure likely allowed it to echolocate, or locate distant or invisible objects by emitting sound waves, which would make it the oldest known echolocating whale.

They named the fossil Cotylocara macei (C. macei): Cotylocara means “cavity head” and refers to depressions in the skull unique to this species, and macei recognizes Mace Brown’s donation of the fossil to the College and also his part in opening the museum.

“The catalyst in all this was the museum,” Geisler says. “That’s what took it from something we all wanted to do, to something we could actually do.”

It was, in fact, what allowed them to spin their hunch about Brown’s fossil into a thoroughly researched article that appeared in the scientific journal Nature this past March.

“Having our work published in Nature is very exciting,” Geisler says. “It signals that our findings are of broad interest to the scientific community and anyone interested in evolution, not just specialists in our field.”

It’s also an opportunity to bring more attention to the Charleston area as a prime location for fossil discovery.

“Hopefully it’s not too high of a bar,” says Geisler. “Either way, this discovery is just the start.”

For Carew, Geisler and Havenstein, it’s been the start of something more personal, too – connecting the professor and two alumni with a new level of friendship and professional partnership.

“Having a student be successful and then come back to work together is the ideal thing for someone like me,” says Carew, who stays in regular touch with Havenstein, even accompanying him on a fossil-diving expedition here and there, and remains impressed by Geisler’s dedication to the field – something that began in 1992, when Geisler wrote a paper about whale evolution for Carew’s class.

It should come as no surprise that, when Carew was moving his office from the Rita Liddy Hollings Science Center to the new School of Sciences and Mathematics Building in 2013, he came across that old paper.

Sometimes things just fall into place.