by Christopher Day

I have spent the past 20 years traveling to Uganda – as a tourist in the late 1990s, as an aid worker in 2004 and as a researcher for the past decade, where I study issues of peace and security in Africa.

At the College of Charleston I teach a number of courses about Africa as an assistant professor of political science and a faculty affiliate with the Women & Gender Studies Program. In teaching these courses, I do my best to illuminate issues of both gender inequality and progress that exist in many parts of Africa, including in Uganda.

During my frequent research trips to Uganda, I have been fortunate to have as my host Brigadier Dick Olum of Uganda’s national armed forces, whose family has embraced me as one of their own. In fact, I’ve spent my last three birthdays with them at their home in Kitende, just south of the capital city of Kampala.

Two years ago, I was eating lunch with Dick’s four terrific kids and his wonderful wife, Patricia, when she turned on the TV to show me something. Ugandan state television was airing an International Women’s Day ceremony, where President Yoweri Museveni was bestowing an honor to one woman in particular. It was to Kate Rukiidi, Patricia’s mother.

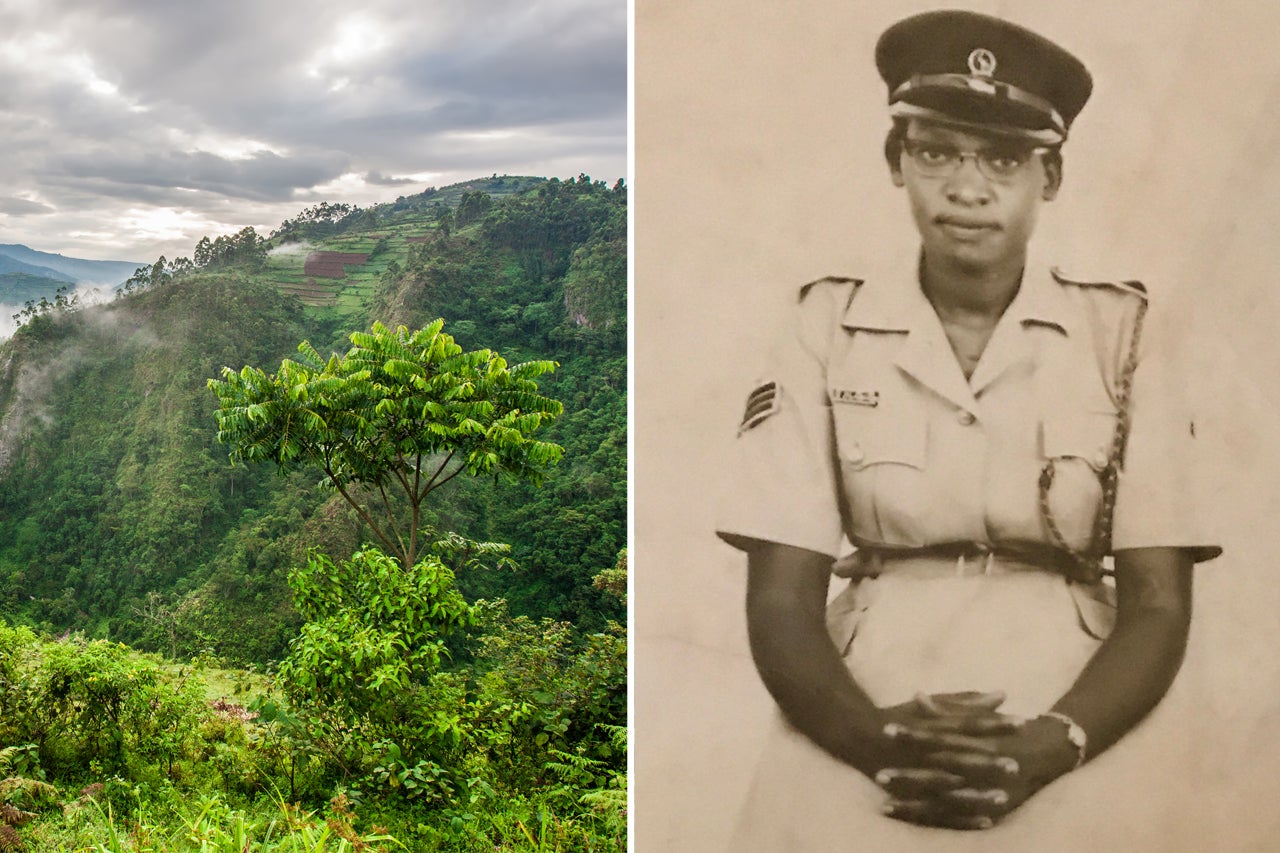

Rukiidi was one of the first eight women to serve in Uganda’s police force, beginning the job just before the country’s independence in 1963. She was 22 years old. In March 2017 I had a chance to sit down with her and learn more about her story.

Kate Rukibi and Ugandan History

Rukiidi’s professional trajectory reflects changes in Uganda’s politics and society over several decades. During the late colonial period, the police in Uganda were part of the coercive arm of the colonial state. Rukiidi’s uncle, unusually tall, was one of the few policemen from the Batoro ethnic group in a force dominated by northern Acholi and Langi, who were viewed as “warrior like” by colonial officers. In the twilight of British colonial rule, the police reduced its height restrictions to 5 feet 6 inches, allowing Rukiidi to follow in her uncle’s footsteps. She signed up for training.

During the 1960s, much of Africa was optimistic about political independence and the future. A police officer in Uganda earned 240 Ugandan Shillings a month, a decent enough income for Rukiidi to pay the bills, to dress how she liked, to eat what she liked, and to save some money. Soon she and her husband, the first Ugandan High Commissioner for Prisons, began to raise a family of four as members of Uganda’s small middle class.

Yet things took a nasty turn during Idi Amin’s regime of the 1970s. After opening several new police branches throughout Uganda, Rukiidi was soon “retired in the public interest” for reasons she still does not understand. Presumably, the winnowing of the police force was part of Amin’s broader strategy of purging the state’s security apparatus and stocking it with his ethnic kinsmen from Uganda’s West Nile region.

Then came the atrocity: In April 1977, Rukiidi’s husband disappeared. While his fate remains unknown, he was most likely among the estimated 300,000 Ugandans killed under Amin, many of whom were brutally dispatched by the innocuously named “State Research Bureau,” Amin’s secret police charged with neutralizing perceived threats to his paranoid, floundering autocracy.

Amin’s regime fortunately fell in 1979. Now a single parent, Rukiidi was reinstated into the police force with the full rank of Inspector. But Ugandan politics were far from settled. In 1981 a civil war broke out between the government and the National Resistance Army (NRA). Many who joined the NRA rebellion were Batoro from Rukiidi’s home region of western Uganda. Yet based in Kampala, she remained largely insulated from the country’s descent into violence. After the NRA’s 1986 victory ended the country’s civil war in 1986, Uganda once again gave way to what, in her view, were better times. She continued serving as an Inspector and received further training in airport security in the U.K. Rukiidi retired in 1993 and soon started a private security firm in Kampala as Uganda began to find its footing as a relatively stable country in an unstable region.

Women in Africa

Rukiidi’s access to education and employment stands in contrast to broader patterns of gender inequality in Uganda in particular, and most of Africa in general. According to the World Bank, there are still fewer girls than boys receiving public education in Africa. And while maternal mortality rates have declined, a woman in Africa still faces a 1 in 31 chance of dying during childbirth, a striking contrast to her developed world counterpart’s 1 in 4,300 chance. Indeed, recent data shows that sub-Saharan Africa accounts for nearly two thirds of the world’s maternal deaths.

Economically the picture is also far from encouraging. According to the United Nations Development Programme, African women reach only 87 percent of the human development outcomes of men, hold 66 percent of jobs in the informal sector outside of agriculture and make only 70 cents on the man’s dollar. This gender gap in Africa is estimated to cost the continent $95 billion annually.

Undergirding such statistics are durable social norms that marginalize women , and increase their vulnerability to domestic violence and harmful traditional practices. The African Development Bank (ADB) shows that some customary land tenure practices exclude women from land ownership, while political and institutional barriers restrict their access to credit and, most importantly, a whole range legal rights. Even in Uganda, which ranks a progressive 13th on the ADB’s Gender Equality Index, I learned that a woman must obtain her husband’s permission to get bilateral tubal ligation surgery to prevent unwanted pregnancies.

Gender and Authority in Uganda

Rukiidi’s professional life challenges some common assumptions, but is also in some ways an accurate reflection of inequitable gender roles in Ugandan society.

When she began training in the early 1960s, her father scoffed that she was doing “men’s work,” and few in her village understood the appeal of being a woman in a position of state authority. Throughout her career, Rukiidi faced regular sexual harassment from male senior officers who expected her to “be a woman to every man,” despite her rank and marital status. Those women who “gave themselves over” to their senior male officers tended to jump rank, while those who resisted were branded as insubordinate.

Interestingly, while disrespected by men within the police force, her day-to-day experiences with the public were quite different. The most common crimes she confronted were domestic violence and “defilement” (men having sex with underage girls). When making arrests, men would tend to come quietly believing there was “no need to fight with a woman,” while women put up the most resistance. Moreover, although the police force was strongly associated with corruption, being a woman authority figure somehow inoculated her from this, and most men “wouldn’t dare” offer her bribes.

What gave me a double-take was Rukiidi’s recounting of her fondest memories. These were of the waning days of colonialism and during Uganda’s first year of independence when the British officers still commanded the country’s police force.

To be sure, this is not to make “the case for colonialism” as has been done elsewhere recently – far from it. By most accounts, colonial rule imposed the Victorian notion that political authority was the sole preserve of men, and relegated African women to the domestic roles of child-rearing and subsistence farming.

Yet according to Rukiidi, during this period, at least some colonial officers supported women’s advancement according to basic meritocratic principles. While she found police training physically challenging, women tended to excel in its classroom portion, which essentially became a gender equalizer. As such, Rukiidi was rapidly promoted three times from the day she joined, becoming an assistant inspector by 1965.

Encouraging Signs

Despite the challenges that remain for gender equality in Africa, Rukiidi’s remarkable story of Rukiidi’s might soon become the norm for many women on the continent. Indeed, there are several positive trends. One area of progress is the relatively high percentage of women represented in African legislatures. Indeed, on a recent visit to Uganda’s parliament, I watched a session gaveled in by its first woman speaker, Rebecca Alitwala Kadaga. Of 193 countries ranked by their percentage of women in parliaments, Uganda is 30th at around 34 percent (the U.S. comes in 99th at 20 percent). The world’s leader for women in parliament? Rwanda at 64 percent. Such encouraging changes have largely occurred recently, after long-fought battles to establish gender quota systems.

Meanwhile, these days Rukiidi regularly holds court as the matriarch of a sprawling extended family. Its members regularly pass through to check in on her in the same house she’s had since the 1970s, its walls decorated with photos of her as a young policewoman in uniform. Her advice for young women in Africa? Get an education. Respect yourselves.

Christopher Day is assistant professor of political science and faculty affiliate with the Women & Gender Studies Program.