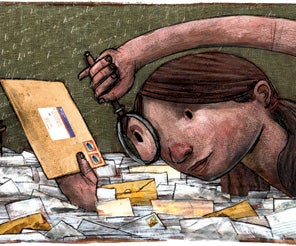

The mailroom is a place of legend. It’s the starting block for many careers, especially in the fast-paced corporate world. But for one alumna, like many writers before her, she discovered the mailroom as an important first step in the race for literary immortality.

by Heather Richie ’02

On May 31, 2013, I quit my job in the College’s Office of Mail Services. I worked there 85 days.

It was my second job at the College of Charleston. My first was in the Writing Lab, where, as an undergraduate, I was a certified advanced level tutor. A decade later, when I joined mail services, I called myself an epistolary narrative specialist. To my knowledge, there is no such thing. The epistolary form is vast, encompassing (for starters, there’s the Epistles) – and, when one looks to a regional or temporal scope (say, Civil War love letters, for example), an epistolary narrative specialist would more likely be called a historian, or, in another instance, a theologian. And, while I do believe that epistolary form does benefit from the psychological assistance of imagining an audience (should one be willing to play games with one’s own mind in such a way), I am hardly a specialist.

I wanted to be like William Faulkner, who they say talked to no one when he worked at the post office, forever scribbling away. But everyone at the College is so nice, and, in the end, I wasn’t even like Eudora Welty’s narrator in “Why I Live at the P.O.” I wasn’t mad at anyone.

There’s no one reason I don’t work at the post office anymore. I left because I just can’t get up at five in the morning, which is when I’d have to get up to write the contemporary fiction that my supervisor, Al Andreano, reads, before going to get the mail. I like Al. I like the books he reads. So, I left for Al.

I left because, however unformed, writing is pretty much what I have.

I left because, a decade ago, then–English professor Carol Anne Davis explained to our poetry class that the university was the last great hideout for the American writer. The economic reality of that guy who could be a doctor and a writer, William Carlos Williams: Those days are gone. I didn’t want to believe her. I spent 10 years joining Teach for America, starting a real estate brokerage, making signs, delivering flowers and, finally, delivering the mail. She was right. It’s not the idea of time, but time itself. So much depends upon it. Without a graduate degree, I didn’t stand a chance.

I started the M.F.A. program at Sewanee the summer before I joined the ranks at mail services. I thought I’d skip summers, earn my degree slowly, methodically. Concentrate on the real job, getting published.

I fell in love with a guy who never, or perhaps only vaguely and momentarily, intended to love me back. That was over a year ago. I’m from Atlanta, but I’m comfortable with Charleston family names: their unexpected pronunciations. Legare. Hasell. Huger. Poulnot. That last one is a joke. It’s pronounced how it looks. Anyway, this guy’s kinfolk work in the School of Education, Health, and Human Performance, I guess, because about biweekly I had to toss letters in their boxes and be reminded of my penchant for unrequited love. And there’s that one out on Sullivan’s Island who sent the CofC Foundation, located in the Sottile House, a donation. I know it was a donation because they have special envelopes for that. His people, it seems, are everywhere. And, apparently, they have money. Not that that’s why I left.

By the way, I never read other people’s mail: That’s a federal offense.

But, about two months into my tenure in mail services, an envelope arrived with a message on its back: The letter’s narrator – no, the sender – had been published in the 1980s in a scientific journal available in “any” college library. The man went on to explain his astronomical theory and how frustrated he was by not receiving recognition about this or that. That bothered me. It was addressed to the College’s president. I don’t know about you, but I’m certain this writer was addressing the wrong man. It’s not our president’s job to see to it every obscure academic’s career stays on track.

Then there was this guy who wrote to a psychology professor nearly every week. In fact, sometimes he wrote to her twice a week. He addressed a No. 10 envelope in the exact same penmanship, sprawling across the exact same amount of surface of the envelope, every time. His words were fontlike, a sort of hybrid print-cursive, and very little of the envelope was ever left bare. Yet the stamp always had ample breathing room. Maybe he was brilliant. Or maybe he just never quit his day job.

The envelope was from the backwoods of Virginia, and it served as a catalyst. I don’t want to write in fontlike penmanship biweekly or in such a frustrated tone. I just want to make a living. In the decade it took my poetry professor’s advice to resonate, I learned the real problem of the writer’s life: I was narrating it in real time, no matter how great a resistance I made to writing it down. I made the decision to go to Sewanee at a time when I knew in my heart that if I merely narrated one more love story, it was because a certain tipping point had been reached – a place in time when the stories in my mind outweighed the stories I had put to the page. I was even losing the art of telling them.

Then it happened: I wrote love letters to a skiff on a blog for Wooden Boat magazine. The skiff was a metaphor for that guy related to those people. Then I wrote an email to this guy’s uncle, and, by the second paragraph, I was making literary allusions. I finally considered my audience for long enough to turn it into a rough draft, call it an essay and submit it to a few journals. It, too, got published.

I’d found my voice, and it felt the same as striking oil. When that happens, people give up their day jobs and keep digging.

Illustration by Nathan Durfee