To join the pantheon of American heroes and villains that populate the WWE, Tyler Kluttz ’06 has scraped and clawed his way to the top through an adrenaline-infused, soul-rattling, backbreaking test of mind, body and spirit. It’s not been a journey for the faint of heart.

Story by Mark Berry

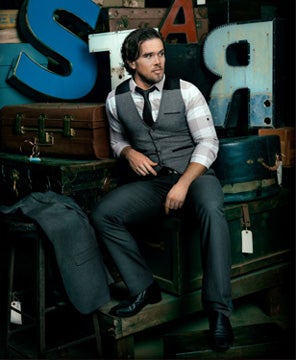

Pictures by Jason Myers

Ssshhh. Everybody, be quiet. It’s about to start.

As the commercial fades, the Kluttz family gathers before the television.

The bell rings three quick times and the TV camera pans over a sold-out crowd for the WWE Monday Night Raw event in Columbus, Ohio. With a ringmaster intonation in his melodic baritone, the announcer calls out, “Ladies and gentleman, the following contest has been scheduled for one fall, and if Brad Maddox wins, he will be awarded a one-million-dollar WWE contract.”

The word million, like a green balloon, hangs in the air a moment.

Around the family room, everyone looks back and forth, giddy with emotion. This is really happening! Tyler’s first big match! their excited glances scream. Right before their eyes, a new page of the family scrapbook is coming to life. It’s like witnessing a birth, a baby’s first steps, a graduation and a wedding, all wrapped up in one, because this moment is happening not only in the presence of the family, but in front of millions of people around the world, right now.

Tyler Kluttz ’06 (a.k.a. Brad Maddox) appears on the screen, and the arena erupts in boos. The Kluttz family laughs quietly to themselves. They don’t blame the crowd for disliking this cocky upstart who is preening in front of the camera. He’s a cheater, an opportunist and, perhaps his worst crime, he’s a pretty boy. But this guy, full of conceit and unmerited swagger, is nothing like our Tyler. No, they don’t know the real Tyler – the smart, sweet, creative soul who is the apple of our family’s eye. They only see this ridiculous character he’s playing: this laughable, arrogant Brad Maddox.

Coming out before gigantic flashing video panels, this small figure in black and silver tights wears a gray leather jacket, more Members Only than Hell’s Angels, with “Brad Maddox” emblazoned in rhinestones on the back. He jumps up and down a few times and swings his arms out as if flying – a slightly stiff, almost child-like Superman imitation. To the crowd and onlookers watching on television, Maddox doesn’t inspire much fear or really any sense of toughness. Rather, there is something about his smug smile – a smile that you want to wipe off with a sledgehammer.

Wow, his family thinks, he’s good at this. They really do hate him.

Tyler’s father, Banks Kluttz, can’t help but shake his head in awe and disbelief. He had not believed in his son’s dream when he first learned of it. Tyler, you’re a college graduate, for crying out loud. What could you possibly be thinking? the father wanted to yell at his son.

But he swallowed his disappointment and didn’t try to stop Tyler going on this fool’s errand. The boy, bless his heart, just has to learn some lessons on his own. Yet now, after years of struggle and determination, that boy was teaching his old man a thing or two about dreams and reality – and the father couldn’t be more proud.

As the Kluttz family and every wrestling fan in the world knows, during these elaborate introductions, music accompanies each wrestler’s entrance, usually a raucous theme song to get the crowd pumped up and on their feet. But as Maddox makes his way down the runway, only the sound of an ambulance’s melancholy wail competes with the crowd’s jeers and taunts. And then the camera pulls back from Maddox’s surprised face to reveal an emergency vehicle backing its way alongside him toward the ring.

Well, that’s a little dramatic, chuckles Banks to himself, looking around the family room decorated in streamers of black, white and red (WWE colors). He can’t help but smile at the rapt faces of his son’s aunts, uncles and cousins holding Brad Maddox signs they had made just for tonight. This is certainly a moment to remember, a moment to celebrate. In the week leading up to this million-dollar match, Banks had scoured the Internet for insight into the WWE storylines and perused several online forums. Based on some of the fans’ speculations, he believes that his son has a real chance at winning. It’s a classic David versus Goliath confrontation, and as a former missionary, Banks knows which side he’s betting on.

Then the camera flashes to Maddox’s opponent, Ryback, a hulking figure who would give even Goliath pause. Ryback’s gargantuan, seemingly comic book–drawn size is the least of Maddox’s problems. If cartoon steam could blow out of Ryback’s nostrils and ears, it would. There’s an unmistakable rage behind those eyes and a monstrous bent to his hoarse voice as he growls, “Feed … me … more.”

His anger is understandable. Maddox, working as a referee just a couple of weeks before, had cost Ryback his championship title by delivering a low blow and then later fast-counting him to defeat. What becomes clear very quickly, to even the casual observer, is that this is not really a contest to win a seven-figure contract. No, it’s a grudge match.

The family, shifting a little nervously in their seats now, watches Maddox trying to escape. They can sense his fear – because they feel it, too. When Maddox is finally caught, it’s a one-way fight. No, fight is not the right word. This is violence – pure and simple. The entire Kluttz family stares at the screen in silence and in shock, some with their hands covering their eyes, at times, peeking through fingers to see if their Tyler – their son, grandson, nephew, brother – can muster any kind of counterattack. Or some sort of defense.

No, that’s not going to happen. Maddox is tossed around the ring like an offending toy to a demon child on a tantrum from hell. He absorbs power slams, power bombs and meathook clotheslines. He endures the indignity of being dragged by his hair and then carted around the ring on the shoulders of a laughing, maniacal Ryback. Maddox is pinned after a relentless 5 minutes and 39 seconds. The ringside commentators laugh about Maddox’s chances in the WWE and revel (a little too much, in the Kluttz family’s opinion) in the “massacre” of this brazen young man who got his comeuppance.

But it’s not over. As the paramedics strap a dazed Maddox onto the stretcher, Ryback’s anger has not subsided. He seethes. He rages. Ryback jumps to the floor, scaring away the emergency team, and flips Maddox headfirst from the stretcher. For the next two minutes – two excruciatingly long minutes – Ryback brutalizes the nearly defenseless figure. And although many fans in the arena cheer on this degradation with “feed me more” chants, others sense that this beating has gone too far – even for their tastes. Maddox the goat has become Maddox the sacrificial lamb before this monster.

By the time Maddox is thrown into the back of the ambulance by the stampeding Ryback, the phones at the Kluttz gathering are ringing and buzzing nonstop. Family members from across the country are calling to check on Tyler. Is he all right? they all want to know.

Is he? his father worries. How could he possibly take that kind of punishment and be OK?

Too many minutes pass before they hear from an aunt who is at the event in Columbus. Of course, she hadn’t seen the two opponents immediately backstage shake hands and congratulate each other on a great performance. When the aunt finally catches up with him, she reports that Tyler looks a little winded, perhaps red and swollen in a few places, but, seeing that mischievous smile again – a smile that infuriates as much as it charms – she knows he is just fine.

Welcome to the WWE.

THE AWAKENING OF A DREAM

We’ve all been there. Stuck behind a desk, staring blankly into a computer screen, feeling our slouched figure getting fatter by the second as the walls of our tiny cubicle close in on us. And we probably daydream enough billable hours to make ourselves a Fortune 500 company a thousand times over.

Tyler Kluttz felt that way. But it took him all of three weeks to determine that the corporate treadmill he was on wasn’t going to take him anywhere he wanted to go.

Kluttz, who earned a degree in business administration, had landed a job with the Charlotte Checkers, a minor league hockey affiliate, selling season-ticket packages. For a recent college graduate, it was a good professional foot in the door, especially for someone like Kluttz, who wanted to get into sports marketing.

But three weeks in and without even one sale next to his name, Kluttz knew that this wasn’t meant to be. During a lunch break, he left the sales office and meandered a few blocks through downtown Charlotte. Standing there along tree-lined South Tryon Street, he made a vow to himself: I will not lead a boring life.

Then, he pulled out his phone and keyed in a 502 area code number. The voice on the other end of the line turned out to be Nightmare Danny Davis, the owner of Ohio Valley Wrestling and dream maker for many aspiring wrestlers. Kluttz asked a few questions, got a few answers and decided then and there to go for it.

This may seem like a decision made in a moment of reckless youth. A classic millennial misstep of impatience and demanding the prize before the work is done. But Kluttz had been thinking about this for some time. Wrestling had always had a strange pull on him. Why waste another second?

Like many fans, Kluttz fell in love with professional wrestling as a boy. He loved the action, the intricate moves and the larger-than-life characters. He would pull off the mattress to his bed, creating an impromptu ring on the floor, and put little sister Caroline Kluttz ’10 into the Scorpion Death Lock until she tapped out three times. Or, he and his buddies would hold matches in their basements, trying out various submission holds and donning different wrestling personalities. Throughout middle school, wrestling was a part of the everyday conversation, but by high school, other interests, as might be expected, took over their imaginations.

In his junior year at the College, Kluttz rediscovered his passion for wrestling. At first, it was just a guilty pleasure, a Monday-night distraction from studying. It certainly beat CSI: Miami or some popular reality show everyone else was watching. Soon, however, he found himself truly admiring the production and presentation of wrestling, appreciating the incredible displays of athleticism and crazy storylines of betrayal, rivalry and redemption that hooked you from week to week. More than anything, it just looked really, really fun.

Now, if you’re not a fan of the WWE, you’re probably dismissing Kluttz’ dream of professional wrestling as somewhat frivolous, just like his father initially did. Naturally, this isn’t Shakespeare in the park or a Broadway drama thrilling monocled culture critics. But if you’re a lover of live performance, you may be missing something here. Like the Taj Mahal or Versailles, the WWE is so gauche that it’s grand. And people love it. A lot of people. Its appeal around the globe is massive, reaching an estimated 650 million in more than 150 countries and in 30 languages. It touches every demographic, every socioeconomic class, even boasting that a third of its viewership is female. But that’s just marketing-speak from a publicly traded company sitting on the New York Stock Exchange. Don’t take their word for it.

Go to an event and you’ll understand its popularity. As the arena gates open, you’ll shuffle along, chest to back, shoulder to shoulder, in a seemingly endless stream of men, women and children, all laughing, smiling and yelling intermittently, “Whoooo.” You’ll see suits and ties mingling with faded Hulk Hogan T-shirts and ripped jeans in the merchandise lines. You’ll observe middle-aged men and school-aged boys with championship belts slung over their shoulders. And almost everyone seems to be carrying a poster-board sign in brilliant colors of neon pink, yellow and green. When the show finally begins, with the arena jammed to the rafters, you’ll feel like you’re at a rock concert, gladiator competition, daredevil act and local theater performance all neatly packaged into one pyrotechnic, eardrum-splitting, throat-rattling spectacle.

As Kluttz succinctly puts it, “It’s just awesome.”

Mike Mooneyham ’76 agrees. As a sportswriter with the longest running wrestling column in the country and the co-author of a New York Times bestseller on wrestling (Sex, Lies and Headlocks), he understands the allure of professional wrestling and admires it for what it is: a unique genre of entertainment.

“Yeah, it’s a soap opera on steroids,” laughs Mooneyham, who is also a longtime sports editor with The Post & Courier in Charleston. “But when Vince McMahon took over the business in the mid ’80s, he transformed it. It’s hard to compare wrestling today to what it was back then, say in the ’60s and ’70s. The WWE is a sports entertainment juggernaut now. You’re talking about a company that garners incredibly high ratings and sellout arenas all over the world, from Charleston to China. And, remember, it just launched its own network in February, so we’re talking about something of Disney-like proportions.”

In that light, Kluttz’ dream is actually pretty audacious.

“It’s harder to get a spot now in the WWE than to get one on a NBA team,” Mooneyham believes. “That’s a pretty small opening. The WWE is very selective. They only bring up the top guys. If you make it, it’s tremendous.”

And that’s what Kluttz intended to do.

LONG WAY TO THE TOP

If you’re an aspiring actor, you go to Hollywood. For would-be wrestlers, it’s Louisville, Ky. At least, that was ground zero for making it to the WWE in fall 2007.

Kluttz packed up his few belongings and his new bride and drove seven hours west from Charlotte to the Derby City. To pay the bills, he found a job waiting tables at Amerigo, an Italian-American restaurant, and then signed up immediately for the beginners’ program with Ohio Valley Wrestling, where they taught ring technique and ring psychology and served as the premier developmental program for the WWE.

His first instructor was Joey Mercury (or Joey Matthews), a wrestling star who believed in an old-school approach to the business: mainly, conditioning. Kluttz and the others soon realized that this class was no joke. Mercury was serious in weeding out those who didn’t have the talent or drive to make it. They learned some basic moves, like arm drags and running the ropes, but on any given day during these two-hour sessions, they would do a thousand squats, perform slow jumping jacks that made their calves feel as if they were wading through fire and do enough push-ups to make them want to throw up and pass out. On top of that, they also did human wheelbarrows in the parking lot, ran wind sprints and, the worst, endured the invisible chair drill – holding that simple, yet excruciatingly painful position for minutes at a time. It wasn’t uncommon for someone to go home after one of these sessions and never return.

“Not Tyler,” Mercury remembers. “He wasn’t there, like some other guys, to play wrestler. The training I put him through was hellacious. I had to see if he could take it.”

He could, and Kluttz moved on to Rip Rogers’ intermediate classes, an even more intense experience, where the focus was on technique and storytelling.

“This class was pretty intimidating,” Kluttz says. “But it was really important in teaching me how storytelling is the centerpiece of the wrestling experience. We learned how to really sell a move in the ring. And also the reality of the profession and how tough it is to make it.”

“You got a 99.9999 percent chance of failure,” observes Rogers, a veteran wrestler and a harsh judge of today’s wrestling product in the WWE. “I have no clue what they are looking for. The wrestling up there is not real. It’s not about the best wrestler anymore. To make it today, you have to be a wrestler’s kid, a physical freak, an ex-NFL player, a reality show star.”

Of course, Kluttz was none of those things, but, even against those stiff odds, he never got discouraged, never thought about giving up. Sure, there were some low moments, but they weren’t driven by self-doubt. Rather, they were driven by impatience: “I was ready for my turn.”

But his turn would take some time. Like other OVW wrestlers who had risen to the WWE – such as John Cena, Randy Orton, Batista and CM Punk – Kluttz dutifully began working his way up, first competing on the local circuit and crafting his wrestling persona. He started off as a villain, or heel in wrestling parlance, named Brent “Beef” Wellington, a member of a fake fraternity – Theta Lambda Psi. This four-man team was made up of stereotypical jocks with the prerequisite bad attitude to match. Kluttz carried a paddle and wore a pink collared shirt and khaki shorts. In some matches, he would peel off one pink collared shirt only to reveal an identical one underneath.

Kluttz loved the crowd’s reaction to his character, the heat he generated from the screaming audience: “As a heel, you can do whatever you want. You get to do and say all the things that in real life, society won’t let you. The more disliked you are, the better job you’re doing.”

Later, as Kluttz developed the Wellington character, he ditched the khakis for traditional tights. To save money (he was still waiting tables), Kluttz decided to make his own. He purchased a sewing machine and a pattern for Spandex tights, becoming Kluttz, the part-time seamstress.

“I thought it couldn’t be that hard,” he laughs now, “but sewing is the most frustrating thing in the world. I figured with spandex, there is room for error. I made every mistake twice. And although I haven’t made a ton of gear, I’ve made all of the gear I’ve worn.”

In wrestling, clothes only partially make the man. Physical attributes aside, the X factor for any wrestler is his ability to communicate. Yes, words matter in wrestling. Cutting a promo (when a wrestler gives his self-absorbed, booming monologue) sets the tone for a match and frames the character of a wrestler. This is where Kluttz found that he really excelled.

“The day I started taking promos seriously,” Kluttz admits, “is the day I started getting decent at them.”

The general advice was to practice them in front of a mirror. But Kluttz found that he couldn’t truly put himself in the moment staring at his own likeness. Instead, he purchased a small video camera, placed it on a shelf at eye level and cut loose.

“Now, I could really go back and study what I was doing,” he says. “I could better critique my delivery, my facial expressions and dissect what was weak, what was strong. I started to do improv on camera as well, taking a word and making a whole story around that one word. By practicing and cutting these promos on video, I found that you can actually get better at it – at communicating your character.”

Conveying those words and crafting that personality in a promo would prove to be the spark that ignited Kluttz’ career.

BREAKING IN

For a year and a half, Kluttz worked his way up through the OVW, perfecting the smug character of Beef Wellington and evoking the disdain of crowds at Davis Arena, the converted armory where OVW held its school and televised matches.

During that time, however, the WWE severed its ties with OVW, effectually ending the Louisville company’s role as a developmental league. Still, Kluttz did not despair. He knew he had the stuff to make it.

The new epicenter was in Tampa, so Kluttz paid $2,000 for a four-day class, which was really a glorified tryout. There, Kluttz hoped to catch the eye of someone, anyone from the WWE, who might offer him a contract. While that didn’t happen, it did put him on the radar to serve as an extra whenever WWE’s Raw or Smackdown shows came near Louisville.

“When you got that call to be an extra,” Kluttz explains, “it’s a chance – at least, sometimes – for them to check you out before a show. When the ring was ready, I would jump up there, just hoping a producer or talent scout would happen to be around and see me, and, just maybe, say, ‘Let’s see a match with these guys.’”

When not in the ring, Kluttz would walk around the arena and try to find anyone who might listen to him cut a promo. It was nerve-wracking and, honestly, humiliating to beg people to take note of you.

“At my fourth event as an extra, I finally got someone to stop and listen to me cut a promo,” Kluttz recalls. “This guy told me that it was outstanding – one of the top three he had ever heard from guys trying out. He told me that he would go to bat for me.”

Later that day, Kluttz was hunting for John Laurinaitis, the head of WWE’s talent relations, just trying to get five minutes of his time. He had been put off several times already, but he didn’t give up. Suddenly, Laurinaitis turned and said, “Yes, I’ve been told you cut this really good promo. Let’s hear it.”

Kluttz, standing in a tiny room in the bowels of the arena, was at arms length from the man who could ink him to a developmental contract, effectively making him a professional wrestler.

“I was a little nervous,” Kluttz says. “I don’t even remember what I said. He listened, just staring at me, and then he was pretty hard on me, telling me some generalities, like ‘start big’ and ‘get their attention, take them on some ups and downs and finish at a high point.’ They actually signed another guy from the OVW that day. Not me.”

Just another bump in the road, Kluttz thought. Don’t give up yet.

Six months later, Kluttz, who had already won the OVW Television Championship and the OVW Heavyweight Championship, had a voicemail from the WWE talent office.

When Kluttz called Laurinaitis back, he couldn’t believe what he heard: “I was thinking about that promo you cut the last time you were here. We want to sign you to a developmental deal and send you to Tampa.”

SLOW BURN

Two more years. TWO MORE YEARS!!!

Kluttz’ impatience is hard to miss. He didn’t expect to stay in the minor leagues too long. In his head, this was going to be a rocket ride to the top.

After moving to Tampa in July 2010, he joined Florida Championship Wrestling, the WWE’s new developmental territory (which was later moved to Orlando and rebranded NXT in 2012). It was a new beginning in many ways, so he ditched the Beef Wellington moniker.

“I always liked the name Maddux, maybe because of Greg Maddux with the Atlanta Braves,” Kluttz says, “but I guess I didn’t like the u in his name. As for Brad, that came from one of the ring announcer girls who told me that I looked like a Brad, like Brad Pitt. There are worse people to be compared to.”

But not everything in Florida was new: He reunited with his first mentor, Joey Mercury.

“When I saw him again,” Mercury says, “I was blown away by his talent as a performer without physicality. He’s very skilled in acting and improvisation. He irritates you and makes you want to strangle him, which is an enviable quality in our line of work.”

There was a lot to envy. Kluttz continued to shine in the ring as well, being named the first recipient of the John Cena Scholarship (which goes to the best wrestler of the month), winning the FCW 15 Championship and claiming the Florida Tag Team Championship.

In August 2012, Kluttz, as Brad Maddox, made the WWE roster. It had been two long years with Florida Championship Wrestling, but he had finally reached the promised land, or so he thought. His storyline pitted him as a rogue referee looking to make a name for himself any way he could. Two months later, Maddox blindsided Ryback in a championship match, costing him his title.

The next week on Monday Night Raw (which was the second-most watched show on television that night, behind Monday Night Football), Maddox appeared before a crowd in Birmingham, England, to explain his actions. His promo – a sympathetic, yet infuriating portrait of a hopeful wrestler – answers the question: Why not me?

“Because I am 6 feet tall, because I weigh 207 pounds, because I am not a freak, or a giant or a monster, or maybe because I don’t have a Mohawk, or I don’t wear a mask, or maybe because I can’t flip three times in the air and land on my feet. But even when WWE officials told me that I would never, never, never, never make it to the main roster of the WWE, my dream didn’t die. It got stronger. I want to be somebody. I don’t care how many people tell me that I am nobody. … Well, I’m somebody now. I’m famous now. People know my name everywhere.”

A week later, the Kluttz family and the rest of the world watched Ryback’s sadistic whipping of Maddox. And then squash match followed squash match – with WWE superstars Brodus Clay, the Great Khali and Sheamus each taking their turns embarrassing the outmatched Maddox.

Over the next months, Maddox was basically dismissed as a wrestler, and his storyline took him to the “company” side of things, where he now serves as the general manager of Monday Night Raw and is involved, Iago-like, in the machinations of the intrigue-filled WWE.

But that means less camera time and not doing what he loves: showcasing his outrageous personality in the ring. “The hardest part of the job is waiting for that storyline,” Kluttz admits. “I’m standing ready for another match. I know I’m close.”

Mercury sympathizes. He knows, all too well, that TV time is a precious commodity to the WWE, and TV time is what everyone there craves and works for, tirelessly and endlessly. “But I do believe,” Mercury notes, “that the more time that passes, the closer we are getting to Brad Maddox’s breakout performance. His best years are still ahead.”

WWE analyst Justin LaBar, writing for The Bleacher Report, also sees a future for Kluttz’ character: “He stands out because he maximizes his on-screen time. Every time I see him, I either laugh in ridiculousness or I laugh at the physical beating he gets. I never want to turn the channel and I do find myself during every WWE program wondering, What will Brad Maddox do tonight?”

That’s the real million-dollar question. What will Brad Maddox do tonight?

For Kluttz, not yet satisfied with where he is, the answer can’t come soon enough.