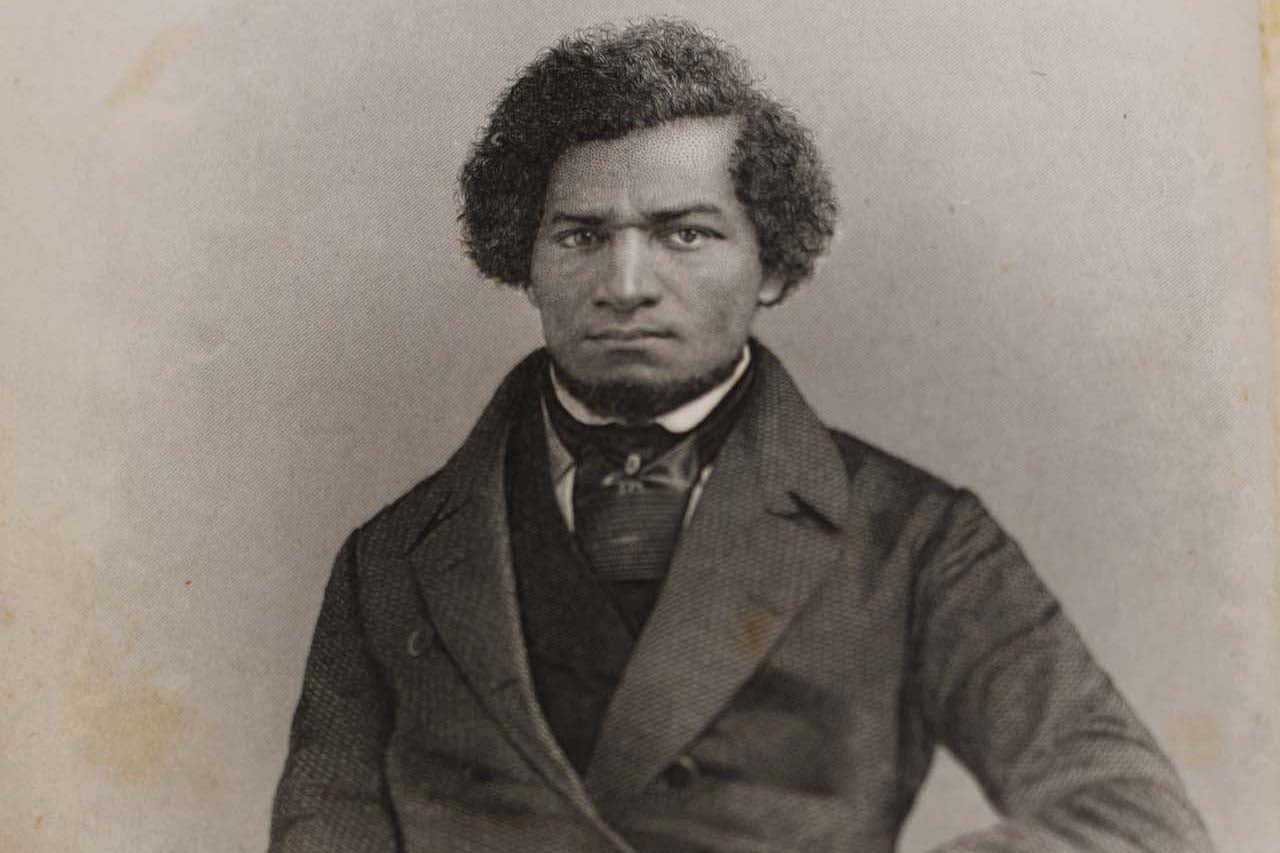

Frederick Douglass emerged on the national stage in 1845 and has never left popular memory.

The power and poetry of Douglass’ words – printed and spoken – fundamentally changed the conversation about slavery in the U.S. and continues to inspire generations of activists.

With Leo and Vicki Williams’ recent gift to the College of Charleston Foundation of a first edition of Douglass’ second autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom, the College of Charleston community now can connect with Douglass in a way typically off limits to all but a fortunate few. The stewardship of this treasure represents the Foundation’s commitment to sustaining the College of Charleston community’s awareness of Douglass’ role in the abolition of slavery in the U.S.

With Leo and Vicki Williams’ recent gift to the College of Charleston Foundation of a first edition of Douglass’ second autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom, the College of Charleston community now can connect with Douglass in a way typically off limits to all but a fortunate few. The stewardship of this treasure represents the Foundation’s commitment to sustaining the College of Charleston community’s awareness of Douglass’ role in the abolition of slavery in the U.S.

Born into slavery in eastern Maryland, the self-taught Douglass escaped to more northerly climes as a young adult. He established himself as a prominent abolitionist, speaking out against the “peculiar institution” at considerable risk to his person. As a fugitive slave, he risked being kidnapped and forcibly returned to his owner – an act protected at the time by American law.

But even in the supposedly safe havens of New York and Massachusetts, Douglass encountered further  discrimination and prejudice. Such was his readiness behind a pen and lectern that many doubted whether Douglass had in fact been enslaved.

discrimination and prejudice. Such was his readiness behind a pen and lectern that many doubted whether Douglass had in fact been enslaved.

His autobiographies assuaged these doubts. Detailing the travails Douglass faced as both a slave and a free African-American, these works rank among the country’s most influential slave narratives and are considered canonical works of American literature.

The Williams’ gift of My Bondage and My Freedom offers a candid look not only at Douglass’ early life, but also at his struggles against racial segregation in the North.

Or, as Douglass himself put it: “Beware of a Yankee when he is feeding.”

For the couple, My Bondage and My Freedom holds a personal significance.

“For nearly four years, I lived across the street from Douglass’ home at 14th and W streets in Washington, D.C.,” says Leo Williams, a retired Marine Corp Reserve major general and Ford Motor Company executive. “Every morning, as I walked out of my front door, the Douglass home was the first thing I saw. I visited his home often. I occasionally walked the route he walked daily from his home to Capitol Hill, crossing the Anacostia River twice each day. For me, Douglass is an up-close and personal hero.

“And then, there’s Vicki’s family’s history with Avery,” the current Friends of the Library Board member adds, referring to the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture, where the book will be kept.

Indeed, for Vicki Williams, the connection is familial: Her mother, Bernice DeCosta Davis, and uncle, Herbert DeCosta Jr., are alumni of the Avery Institute, a school for African-Americans during segregation for which the center is named. She is also a direct descendant of Ellen and William Craft – fugitive slaves whose daring escape to freedom led to their own published narrative, 1860’s Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom.

The My Bondage and My Freedom will be housed in the permanent collection of the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture.