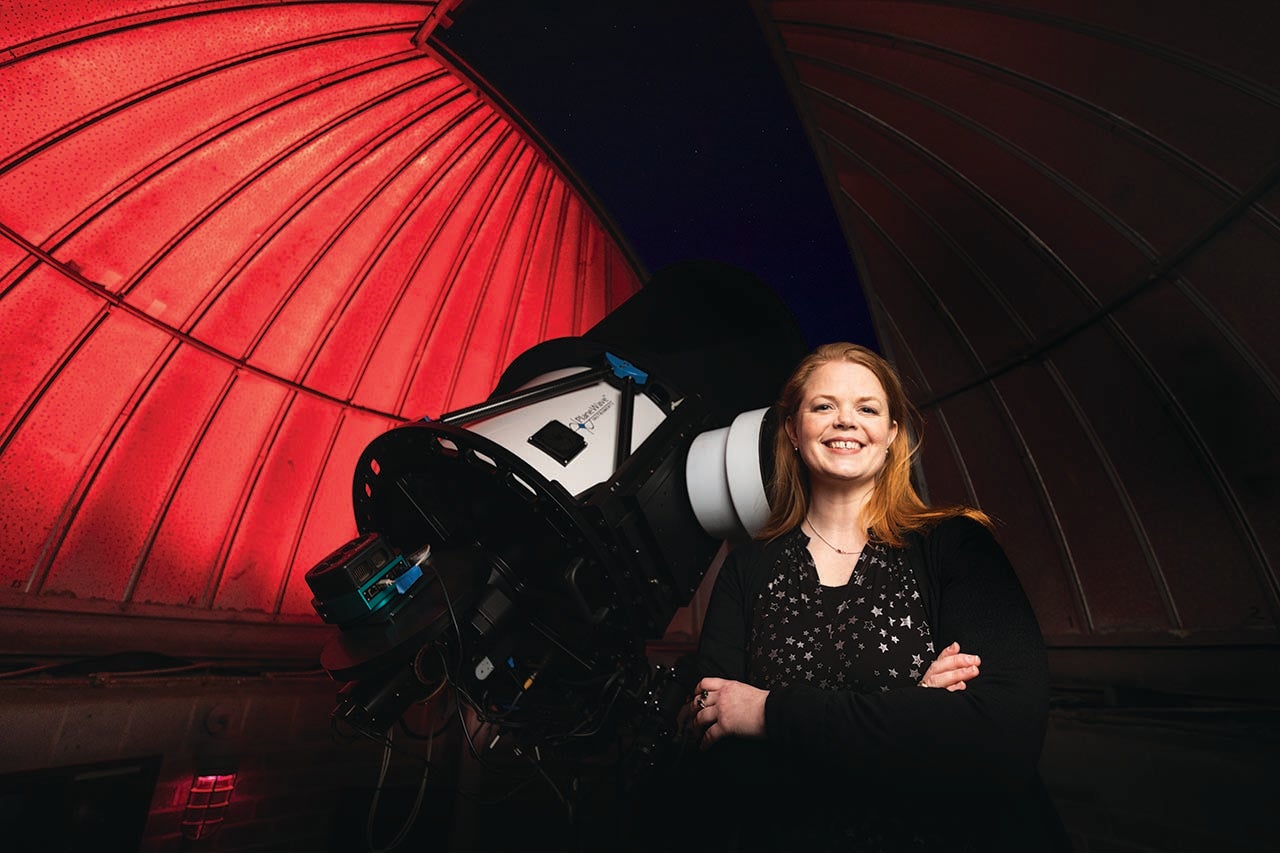

Astrophysicist Ashley Pagnotta gets animated when she talks about her research, and why shouldn’t she? It’s only the fate of the universe that’s at stake. Pagnotta is researching exploding stars and dark energy, which comprises 70 percent of the mass energy of the universe. Instead of galaxies slowing down their expansion from the Big Bang, this cosmic antigravity caused everything to speed up about 5 billion years ago and could one day result in either “the Big Freeze” or “the Big Rip.” Neither is going to be pleasant.

“Even though both of these possible scenarios are trillions of years in the future, human curiosity drives us to understand them and figure out which one will occur,” explains Pagnotta, an assistant professor of physics and astronomy. “Understanding the details of the current behavior of the universe will help us understand what’s to come.”

The key to determining just how much dark energy is influencing the movement of galaxies is by precisely measuring distances to objects over time. With the help of her students, Pagnotta is studying the luminescence of novae – dead stars that reignite for weeks to months and may get massive enough to explode, resulting

in a supernova.

“If we can better understand where these supernovae come from, we can get more precise distances and get better constraints on the universe’s acceleration,” says Pagnotta. “I’m interested in the connection between these novae with the small eruptions and these supernovae that happen in the same type of system and how that affects the brightness and the distance measurements.”

Fortunately for Pagnotta, she can access a treasure trove of historic images at the Harvard College Observatory to compare images of her novae at multiple times since the late 1800s. Some are available online, but for the best images, Pagnotta and her students Katherine Bruce and Bridget Ierace traveled to Harvard to examine them in person, which they will be doing again this summer.

Before astronomers were able to take photos of the stars with digital cameras, they used photographic glass plates. The interesting backstory is that a group of a few dozen women known as “the Harvard Computers” did all the early computation to calculate the position and brightness of the stars in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

“After we spent a lot of the summer researching novae by using our computers to take measurements, it was great to learn how to do the same thing the old-fashioned way,” says Ierace, a rising senior and double major in astrophysics and physics. “It was really cool being able to work with the same plates that were used historically by many other important women who worked there in the past.”

Pagnotta, who spent five years working on a postdoc at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City before coming to the College in 2017, is happy to be paying it forward and adding to the legacy of women in astronomy.

“Learning how to use the plates is a little tricky,” she says. “I’ve taught our students how to do it. It really reinforces how talented the women who used to work there were.”

The Harvard Computers’ spirit lives on in Pagnotta and her charges.

Featured image of Ashley Pagnotta by Mike Ledford.