Francisco Cantú joined the Border Patrol on the U.S./Mexico border at 23 years old. He was a recent graduate of American University and wanted to gain “on the ground” experience before going into diplomacy, policy making or law school to specialize in immigration issues.

Cantú spent the next four years of his life witnessing and participating in what he calls “the institutional normalization of violence.” The daily dehumanizing occurrences between migrants and border patrol agents haunted him, and he struggled to make sense of such experiences and his participation in them.

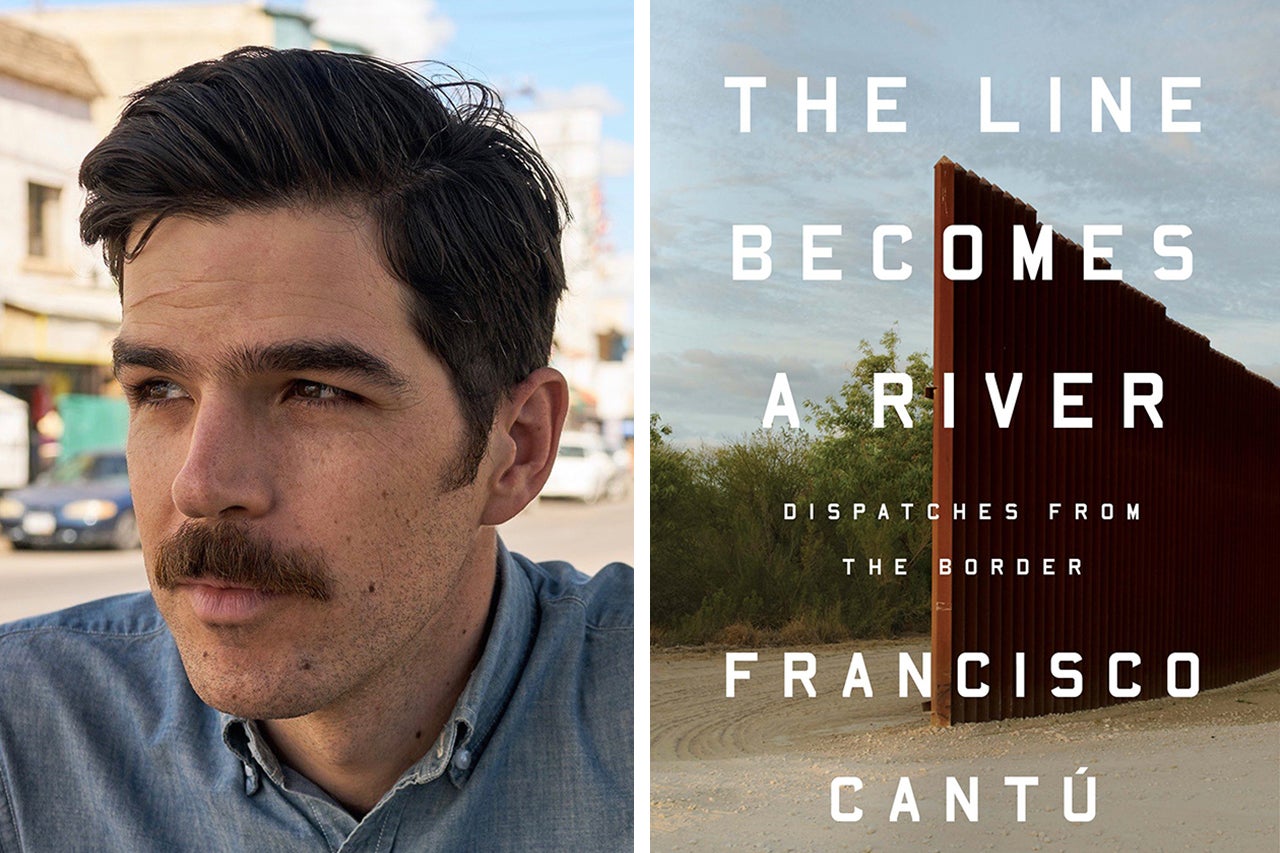

As part of “The College Reads!” program, the College of Charleston will present a virtual evening with Cantú, who chronicled his time as a Border Patrol agent in his memoir The Line Becomes a River: Dispatches from the Border, on Thursday, Oct. 22, 2020 via Zoom. The event is free and open to students, faculty, staff and the community.

Ahead of his virtual presentation, Cantú sat down with The College Today to talk about what he learned as a Border Patrol agent and what he hopes readers take away from his book.

The Line Becomes a River is written as a memoir. Why did you want to write it from the first-person perspective, and why did you shift the narrative in the last third of the book to that of an undocumented immigrant named José?

I wanted readers to inhabit some of the day-to-day enforcement realities of life on the border. The book is a personal story about the power of institutions to normalize violence in individuals, but also in the culture at large. I kept a journal while I was there to record events that were accumulating rapidly, because I knew if I didn’t write it down, the memories would slip into the sea. Much of what is written in the first part of the book is taken directly from the journal entries.

Other voices are introduced in the second part of the book, from research and journalism, about border enforcement and migration experiences. In the last section of the book, I wanted to shift the perspective from inside the institution (of the border patrol) to the individuals most affected by it, like my friend José, and give agency back to them by letting them speak for themselves. Every single person who crosses the border has as deep and complex a story as José.

You describe yourself as being “naive” when you joined the Border Patrol at 23 years old, because you went there thinking that change could be made from within the institution. Many of our students are around that age: What advice would you give them about being naive?

I went there thinking I could gain first-hand experience that would lead to a career as a policy maker or immigration lawyer. I quickly learned that most institutions have become adept over time at subverting the individual’s goals to the goals of the institution. It’s profoundly important for young people not to underestimate an institution’s power to re-direct our good intentions toward their own purpose. My experience taught me that meaningful change most often happens as a result of outside pressure, and so I think it’s important for young people to consider this when attempting to effect institutional change from the inside or the outside.

How has the pandemic has affected the lives of those who live and work at the border?

The pandemic has had a profound impact at the border. For example, there are immigrant families all across the country who might not go to the hospital or seek preventative care for fear of deportation. Many immigrant communities have less resources to isolate. The pandemic has also given the administration pretext to further limit asylum claims and there is a long backlog of cases. People who come to our country for safety are being crowded into detention centers contracted by ICE [Immigration and Customs Enforcement] where there are no means to isolate. These places are incubators of the virus and end up being death camps for people seeking safety.

Where can students go if they are interested in learning more or getting involved in humanitarian work on the border?

I always say that the most important and profound way to get involved is to take action in one’s own immediate community. In Charleston, there are groups like the Charleston Immigrant Coalition. Beyond the local level, there are national groups like Freedom for Immigrants that provide services to detained migrants and do important work to raise public awareness about the injustices of immigration enforcement. Where I live close to Arizona’s border with Mexico, there are all sorts of groups people can donate to or volunteer with to help organize, support and resist on behalf of migrant communities: No More Deaths, The Florence Immigrant and Refugee Rights Project and the Kino Border Initiative, just to name a few.