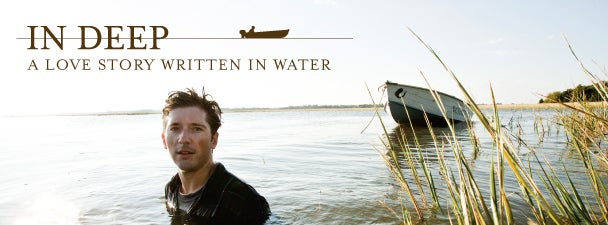

Not all jobs are created equal. For Cyrus Buffum ’06, the Charleston Waterkeeper, he’s found a calling that immerses him in his passion for water and his desire to save the world.

Have you ever loved something so much that you would give your everything for it? Yes, your everything – your every waking moment, your every thought, your every ounce of energy. Would you be willing to commit your youth and even your future to an uphill battle that dips you in and out of poverty like some cruel seesaw, that leaves you – sometimes days, sometimes even months – feeling like a David stripped of his slingshot facing an entire army of Goliaths?

And even in your darkest moments – literally, because your electricity’s been cut off for the last couple of months and you keep telling yourself that you really only need your place for sleep anyway – can you meet each day with a bright and sincere smile? Actually, a smile and a dogged willingness to give it your all, mentally, physically and socially?

You would probably do that for your child. But would you do it for something that can’t say thank you – ever? Would you give your life to something that will never appreciate even one of the thousands of sacrifices you make, day in and day out?

Cyrus Buffum ’06 would – and is.

His love of the water may be one of the greatest romances in human history. While it may seem like his is a story of unrequited love, maybe a tad bit crazy, as great affairs of the heart often are, it’s not. As Buffum will tell you, water, like love, is and has to be pure. For him, water is really the only thread that connects us all – as a people, as a planet, as life. And if that thread frays, as it seems to be doing, all will be lost.

But there’s hope. Love, Buffum believes, will triumph. Not just his love, but our collective love will make the difference when we wake up and finally realize that this is really our love story with water.

The Dreamer and the Doer

The September sun shines within a canvas of deep blue. Today is one of those late-summer days in the Lowcountry that scatters artists across the Charleston peninsula in hopes of finding their magical spots and soaking in some of this inspiration beamed

in azure.

They would find a lot to be inspired by at the Seabreeze Marina, located in the shadow of the Arthur Ravenel Jr. Bridge. A squadron of pelicans flaps silently under the span, swooping low in search of food. The water shimmers and sounds like blue television noise – hypnotic, impossibly relaxing. There’s also a gentle shushing sound of distant cars crossing the Cooper River, accompanied by the light thudding bass of sailboats and Key West skiffs rocking in their slips against the dock. Only the shrill chatter of seagulls occasionally disrupts this tranquil morning scene.

Cyrus Buffum steps onto the dock and takes a deep breath, the kind of breath a cliff diver makes after struggling from unseen depths and finally breaking the surface. The weight of the world seems to disappear with just that one breath. Man, it feels good to be alive, thinks Buffum, to be right here, right now.

Ever since he took his first sailing lesson at age 12, the water has been a playground of sorts for Buffum. Through regatta racing at Wianno Yacht Club in Osterville, Mass., he discovered that the water was an amazing place to challenge yourself, to push yourself to new limits of endurance and quick thinking. As any sailor will confess, whether off Cape Cod or South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, the ocean can be an unforgiving mistress, and it requires a total commitment of your attention, total immersion in the moment. Without hesitation, Buffum became an enthusiastic devotee.

“Water was like the Wild, Wild West to me,” Buffum says. “It gave me a chance to conquer the unknown. I think it taps into that frontiersman mentality our country was founded on. Water is a road that is constantly changing, and it makes you rely more on yourself. That translates into a greater sense of personal independence.”

During his teen years, water grew into something much more than a recreational diversion. It became his sanctuary. Whether on the shoreline or on a sailboat, the water – cool against his fingertips – always reminded him that there was something bigger out there than himself. That the problem of the moment – a bad grade, an argument with a girlfriend, his parents’ divorce – was pretty small in comparison to the vastness of the ocean.

Standing on that dock at Seabreeze Marina, breathing deeply of the salt air, Buffum is again in a spiritual moment. Dragonflies hover nearby. Small, yellow sulfur butterflies dance in the breeze. A dolphin briefly surfaces. The water transports him to a place of constant calm.

But then life intrudes, as it always does. A forklift, beeping like an unsympathetic alarm clock, reverses toward the dock. Air brakes from a passing tractor trailer screech at the nearby port. A muffled, monotone voice calls out names and instructions on a distant intercom.

Buffum smiles, his reverie broken. But he doesn’t mind. Those industrial noises don’t grate on him as you might expect from an environmentalist. His role as the Charleston Waterkeeper, as he sees it, is to help everyone, and that includes businesses, to better understand their relationship with the water. Because the water, he knows, is many things to many people.

Buffum smiles, his reverie broken. But he doesn’t mind. Those industrial noises don’t grate on him as you might expect from an environmentalist. His role as the Charleston Waterkeeper, as he sees it, is to help everyone, and that includes businesses, to better understand their relationship with the water. Because the water, he knows, is many things to many people.

Boiling Point

The title “Waterkeeper” sounds like something medieval, perhaps even post-apocalyptic. Why does Charleston need a Waterkeeper? How, frankly, do you “keep” water?

For Buffum, it’s a bridge of avocation and vocation. It’s a career that was an idea that he worked tirelessly to make into a reality. In many ways, it’s the natural culmination of his passion for water and his need to solve problems.

But Buffum wasn’t the first to gravitate to this idea of preserving and protecting the water. That honor goes to a group of men and women who, in 1966, formed the Hudson River Fisherman’s Association, a citizen-advocacy group who wanted to ensure the health of their waterway against industrial polluters. By 1983, they had hired the first full-time Riverkeeper, who patrolled the Hudson River and served as the primary watchdog against offenders of environmental laws.

Over the course of the next two decades, this grass roots organization attracted the attention of many waterside communities, which began to see how Riverkeepers, Baykeepers and Waterkeepers could benefit them without hurting their local economies. In 1999, the Waterkeeper Alliance was founded to organize these environmental programs, and today boasts nearly 200 Waterkeepers working on six continents.

But Buffum didn’t know any of that until much later. Like most teenagers, he was too busy growing up – and too busy learning the finer points of sailing, exploring the waters of West Bay and Nantucket Sound and discovering his college destination close to 700 nautical miles south along the Atlantic coastline.

As environmental groups toiled to bring about changes in legislation and keep government agencies accountable for industrial polluters in the early 2000s, Buffum was enjoying the intellectual freedom that a liberal arts and sciences university like the College of Charleston has to offer. He devoured all his subjects, finding connections and common ground in literature, philosophy, languages and the sciences. Each class seemed to open new doors of thought and raise even more questions about the things around him. It was a lot to consider – and he loved it.

As a college student, Buffum had something special. Yes, he was smart, energetic, gregarious, fun to be around. But so are a lot of people. Although he looked like your typical college guy – well-worn T-shirt, shorts, flip-flops, sunglasses and an ever-present Red Sox cap, weathered just to his liking – there was definitely something different about him. As physics professor Jeff Wragg notes, “There’s a special twinkle in Cyrus’ eye.”

“He’s someone who radiates this amazing vibe,” agrees Ian Wheeler ’06. “When you meet him, you just know that he has this Thing. I don’t know really how to describe it. He just has It.”

“Yeah,” Chris Robinson ’05 adds, “when Cyrus walked into a room, everyone noticed him right away and wanted to be around him. Sure, he had this way of dancing that just made you stare and laugh. It always cracked me up – it was a true showstopper. But he was also the guy that people cornered and opened up to because he’s so genuine, so bright. Perhaps the most telling thing is that almost his entire family moved to Charleston after he came to school – that’s how magnetic a personality Cyrus has.”

“Yeah,” Chris Robinson ’05 adds, “when Cyrus walked into a room, everyone noticed him right away and wanted to be around him. Sure, he had this way of dancing that just made you stare and laugh. It always cracked me up – it was a true showstopper. But he was also the guy that people cornered and opened up to because he’s so genuine, so bright. Perhaps the most telling thing is that almost his entire family moved to Charleston after he came to school – that’s how magnetic a personality Cyrus has.”

That magnetism would serve him well in his campus involvement. He was an active participant in the College’s Emerging Leaders program and a member of the Student Government Association, serving as chief of staff and a senior senator. And through those connections, he joined a close circle of friends who, as Wheeler describes, were more interested in starting their own legacy than being a part of an established one. Together, they became founding fathers of Pi Kappa Alpha, a fraternity that grew to be one of the largest on campus during their time in school.

But Buffum wanted more.

“Cyrus has always been a dreamer,” says Courtney Clarkson ’06. “He’s the type of dreamer who’s always enthusiastic and excited about everything … who’s always had a ton of big ideas and wanted to make things better.”

The opportunity to “make things better” came to Buffum in a song – specifically “Elias” by Dispatch, a Vermont-based rock band that he listened to in high school. The song was inspired by a gardener in Zimbabwe who dreamed of sending his sons to college. Through the popularity of that song, a nonprofit was organized in 2005 to help Zimbabwean youth get an education.

Eric Byington, cofounder and director of the Elias Fund, remembers receiving an e-mail out of the blue from Buffum, who expressed an interest to get involved in the cause.

“More often than not, these unsolicited inquiries don’t go anywhere,” Byington admits. “The person may have great intentions, but little initiative. In fact, we didn’t hear from Cyrus for a while, and we assumed he had fallen away.”

But what Byington didn’t realize was that Buffum was working furiously behind the scenes to pull different campus groups together to raise money.

“Suddenly, we hear again from Cyrus,” Byington recalls, “and he’s planned a movie screening, speaking engagements and a Friday-night concert. We spent four days in Charleston, and I got to know him pretty well. He’s an all-around fantastic guy, certainly driven, and we stayed in touch. Later that spring, I invited him to go with us to Zimbabwe for six weeks, and he accepted.”

In Zimbabwe, Buffum, a fresh-faced college graduate, started putting the pieces together. His physics degree had taught him to analyze possibilities, to weigh cause and effect. And he had much to ponder as he looked around him in his dismal surroundings.

“Cyrus is good at playing what if,” explains Professor Wragg, who taught Buffum in his Modern Physics class. “Physics majors are not all about laser beams and atom bombs. We’re thinkers about initial situations and consequences. Even complicated situations have simple underpinnings. You start looking at it simply because if you can’t address it simply, you can’t address it at all.”

What Buffum saw was very complex, indeed. A country ravaged by financial and ecological mismanagement. A people held hostage by a dictator. A place with one of the lowest life expectancies in the world. Everywhere he turned, the country was in crisis.

But despite the HIV/AIDS epidemic, the food shortages and the lack of educational opportunities and healthcare resources, the people were resilient, even optimistic. When Buffum looked into their eyes, he saw not the vacant stares of victims, like he’d seen so many times in TV commercials; rather, he saw a smart, proud people searching desperately for solutions.

“Before we left for Africa,” says Clarkson, who also went on the trip with the Elias Fund, “Cyrus was kind of all over the place – in a good way. When we were thrown into this uncomfortable situation, he just totally thrived. He opened up to everybody. He was like a sponge, taking everything in and wanting to figure out ways to help.”

“Before we left for Africa,” says Clarkson, who also went on the trip with the Elias Fund, “Cyrus was kind of all over the place – in a good way. When we were thrown into this uncomfortable situation, he just totally thrived. He opened up to everybody. He was like a sponge, taking everything in and wanting to figure out ways to help.”

Around this time, Buffum picked up John Cronin and Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s The Riverkeepers, a book detailing the Hudson Riverkeeper’s efforts. It was one of those books in which each page seemed to speak directly to him. It was history, politics, environmental philosophy, finance, but above all, an impassioned rallying cry to do something. Buffum had seen in Zimbabwe what a degraded waterway looked like up close, how it hurt the people and limited their possibilities. He knew Charleston lacked a watchdog group dedicated to its waters, and in scientific parlance, he knew the Aristotelian theory that nature abhors a vacuum.

Now, it was time to fill the void.

Time and Tide

The boat slows to a puttering crawl in the No Wake zone of Hobcaw Creek, a winding, watery path that skirts along some very expensive real estate in Mt. Pleasant, near the Wando Terminal of the S.C. State Ports Authority. Buffum pulls out his black notebook and jots down the location from his handheld GPS.

“Can you pull up on the embankment?” Buffum asks Bart Beasley, a volunteer boater working with the Charleston Waterkeeper out in the field that day.

Two 30-foot sailboat hulls, their keels mired in pluff mud, list a few feet away from the creek at low tide. One boat reads, “F-O-R Because, Howell, MI” and the other’s name is scraped off past recognition. It’s a scene reminiscent of Charleston after Hurricane Hugo: of boats unmoored and tossed randomly about the torn landscape. But these boats are not the victims of nature, they’re the product of human neglect.

Beasley’s boat scrapes up on the creek’s bank. Buffum scribbles some more in his notebook, tucks it in the back of his pants and then throws a rope up onto the stern of one of the abandoned boats. Like an acrobat, Buffum lifts himself up and teeters along the broken railing. He peers into the hatch and sees empty Dasani water bottles, old DVD cases and the ubiquitous PBR bottle, half full of water and mud. A long, yellowed plastic tube runs from the cabin and dangles over the side, swinging slowly in the breeze.

“It looks like someone was trying to siphon the water out,” Buffum calls from the boat. He notices two deep tire tracks in the pluff mud just off the bow and a broken television set half-buried in the marsh grass. “I guess they stripped everything of value.”

Buffum balances on the railing and writes a few more things in his notebook, his head shaking slightly as he looks around.

“The State of South Carolina recently passed legislation banning the abandonment of watercrafts,” explains Buffum, “because these vessels not only pose a threat to the safety of recreational boaters, they’re also environmental hazards, eyesores and economic burdens. The recent statute, enforced by the state’s Department of Natural Resources, delegates the responsibility of removing these vessels to local municipalities. And as a result, unfortunately, it’s now an ‘every man for himself’ environment.”

In an effort to help local governments find these abandoned boats, Buffum has created an open-source map that he hopes the entire community will access and add up-to-date information.

“Every local fisherman knows the location of an abandoned boat or two,” he says. “After all, that’s where the fish hang out in the summer. And every sailor knows which side of the channel to hug to avoid running into a submerged object, and just about every person driving over the Ashley River Bridge has seen the cluster of abandoned boats left dying along the marsh. We’re trying to tap into this collective knowledge and compile an inventory that can help address this serious problem.”

“Every local fisherman knows the location of an abandoned boat or two,” he says. “After all, that’s where the fish hang out in the summer. And every sailor knows which side of the channel to hug to avoid running into a submerged object, and just about every person driving over the Ashley River Bridge has seen the cluster of abandoned boats left dying along the marsh. We’re trying to tap into this collective knowledge and compile an inventory that can help address this serious problem.”

Buffum inches his way back to the stern and drops carefully onto Beasley’s boat. There’s almost a look of betrayal in his eyes, an inability to fathom why someone would leave something so valuable like a boat, and just discard it like some piece of litter. And why so many?

“Cyrus is smart, energetic, full of ideas,” says Joe Payne, Casco Bay (Me.) Baykeeper, who was one of the founders of the Waterkeeper Alliance and who approved Buffum’s membership as a Waterkeeper in 2008. “But what’s most important is his passion. He’s offended by the bad things that happen to the water around Charleston. He feels it personally.”

Christine Ellis, the Waccamaw Riverkeeper in Conway, S.C., agrees about Buffum’s passion. But passion, she points out, will only take you so far.

Becoming a Waterkeeper isn’t the declaration of an environmental enthusiast, it’s a structured process. For close to a year, Buffum worked around the clock to meet the guidelines and quality standards to be a licensed Waterkeeper. He researched the threats to the Charleston watershed and created an action plan. More important, he also raised funds for his position and a boat, created a 501(c)(3) organization, secured office space and developed strategic membership drives and educational programs.

“Ultimately, a Waterkeeper must be a strong leader, capable of educating the public about the importance of their waterbody and its protection,” Ellis says. “Pretty much singlehandedly, Cyrus has developed the Charleston Waterkeeper into an impressive education and advocacy program. His energy and enthusiasm are contagious and, without a doubt, he’s a force that cannot be ignored, not only locally, but statewide and nationally.”

On the national level, Buffum raised his profile this past summer by jumpstarting the Save Our Gulf campaign. Like many Americans, he was outraged by BP’s inability to stem the millions of gallons of oil pouring into the Gulf of Mexico. He knew that this might be one of the greatest environmental catastrophes in history.

But as Buffum believes, anger without action is pointless, so he acted. He created a website to raise funds to help those Waterkeepers on the front lines of the Gulf as well as to educate the public about the clean-up efforts and detail ways they could get involved. He even cut a public service announcement with Kick Kennedy, an ambassador for the Waterkeeper Alliance (and daughter of Robert F. Kennedy Jr.), and actress Amy Acker.

But Buffum’s no armchair quarterback. He had to see for himself what was going on there. Was this like Zimbabwe? Was it worse? In July, he flew down to Mobile, Ala., with Keith Sauls ’90, a Charleston Waterkeeper supporter, and then traveled to New Orleans in a converted 1978 Blue Bird school bus called Busta Ride, driven by other Charleston Waterkeeper supporters.

“The images the media caught of birds drenched in oil and dead fish floating on black eddies, the smell of oil on the beaches,” recalls Buffum, “were all horrible. But what stood out most to me were the people and the psychological impact it had on them. Their livelihoods were vanishing. Their water was dying. They were completely devastated.”

The trip, the spill – they reminded Buffum why he had become a Waterkeeper. It wasn’t to save turtles and fish, although that was important. Clean water, according to Buffum, is a basic human right – a basic freedom. Just as important as the freedom of speech or the freedom of religion. Without clean water, the entire ecosystem falters, us included. Those other freedoms in the Bill of Rights don’t even exist then.

Part-time Crusader, Half-hearted Fanatic

Buffum’s boat veers left from the Cooper River into Shipyard Creek, skirting along the Charleston Neck, where iconic Charleston homes give way to factories and industrial complexes. It becomes apparent pretty quickly that this is a Charleston scene you won’t see captured in postcards.

Immediately, the smell hits Buffum. It’s familiar. Methane. Burning wood. Like a polite houseguest lighting a match in the hallway bathroom.

The boat slows down and drifts in silence. Just moments ago, on the Cooper River, Buffum marveled at the wildlife. Mullet jumping around the boat. Birds squawking overhead. A sea turtle paddling nearby. Here, in Shipyard Creek, nothing. The water even has a black, inky quality to it.

“No,” Buffum observes, running his fingers in the water, “I wouldn’t swim in it. And I certainly wouldn’t eat anything caught here – if there were anything to catch.”

The job of the Charleston Waterkeeper is manifold. One day, it may be putting together a group of volunteers to pick up trash along the beach; the next, identifying and recording abandoned boats; then, maybe it’s a workshop with a community group to educate them about the serious problems of run-off from Charleston’s roads and paved areas; or, it’s talking to a group of first-graders about the importance of the waterways and then leading a training session with citizen spotters regarding marine debris. But perhaps the most important work to Buffum is his role in serving as a watchdog against industrial polluters.

He dips a jar in the water and closes the lid, marking carefully its GPS location in his notebook.

“We’ll send this off to a lab to determine the water’s quality,” says Buffum, who would eventually like to expand his team to include a full-time scientist dedicated to sampling and testing. “I’m not some kind of alarmist when it comes to pollution. I’m totally data driven. I want to record accurately what is happening to our water so that we can work together to fix it.”

Under the Clean Water Act, Buffum and other Waterkeepers are able to serve as watchdogs through the citizen suit clause, which effectively means they can sue on behalf of the public when an individual or company is polluting the water. Sounds simple, but there’s a wrinkle.

Also under the Clean Water Act, companies are able to apply for National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System permits, which allow them to discharge certain pollutants within a specific range.

“Yes,” Buffum says, “companies can be legal polluters. In South Carolina, DHEC gives out these NPDES permits. However, it’s the responsibility of the individual company to record the levels of pollutants in their discharges into the water. Then, that paperwork goes to DHEC, where only one person is responsible for reviewing all of the records. Basically, the system is dependent on a company self-reporting its violations, or you need whistleblowers to say that their company is exceeding their pollutant limits.”

Not very effective, Buffum believes. And that’s where he wants the Charleston Waterkeeper to step in and make sure these companies are staying within the ranges of their permits.

“Over the next five years,” he says, “I would like to do a complete audit of the Charleston waters so that we have an accurate baseline to work from in the future. Too many companies see the water as just another commodity – a low-priority line item in their budgets, if you will. That’s why so many of them do their dumping at night or their pipes are below the water’s surface. It’s kind of the out-of-sight, out-of-mind approach.

“Water is our resource,” Buffum adds, the passion in his voice rising. “It’s part of the public trust. I want to make sure companies are not just taking careless environmental shortcuts for short-term profits, but they’re making informed decisions based on their long-term impact in our community and the scientific data we collect.”

Of course, this doesn’t come without some sacrifice, they may say. And Buffum understands that. Perhaps he knows better than anyone this concept of sacrifice.

Buffum didn’t start the Charleston Waterkeeper to get rich. Far from it. For far too long, he didn’t get paid at all. But Buffum didn’t see it as suffering. He saw it as simply treading water because he knew eventually things would take off as more people learned about the Waterkeeper cause.

So, he went homeless for a while. At that point, he was borrowing and sharing office space from TheDigitel, an online news company. Each night, the staff members would wave to him and ask him to lock up on his way out. Gosh, they would think, this kid is one hard worker. He’s the first one in and the last to leave.

They were partially right. What they didn’t know was that Buffum would pull out his sleeping bag and make himself comfortable, pulling two chairs together to make an impromptu bed. Or, he would leave for a few hours, crashing on a friend’s couch that night. Buffum didn’t mind – he knew it was temporary, even if “temporary” meant a couple of months.

Then, when he did move into a house, he had to make some tough choices regarding bills. His cause came first – electricity didn’t even make the Top 10 on his priority list. He learned to shower, get dressed and keep home in the dark. Again, no worries, he thought, I can do this for a month or two.

And he was right. There was a light at the end of the tunnel. His power was eventually restored, and, by that time, his work as a Waterkeeper was gaining more and more attention from the Charleston community.

“Cyrus thinks with this sense of clarity,” notes Mike Scarpato ’06, Buffum’s former roommate in a 400-square-foot home in downtown Charleston. “He’s always thinking on a different wavelength … always has. Maybe someone on the outside looking in might think he should be miserable, but he’s not. Yeah, he’s an idealist, but Cyrus has specific goals, and he knows how to make

it work.”

And each day, he finds a way to make it work. Building relationships in the community. Forging partnerships between environmentalists and businesses. Basically, making a difference in the way people perceive the waters of Charleston.

“I’m lucky in that water is not a polarizing issue,” Buffum admits. “It’s not something that people can debate or argue against. It’s one of the only issues where everyone can see eye to eye. I just need to tell the story in a way that speaks to each individual – the surfer, the tugboat operator, the skier, the sailor, the fisherman. I have to remind them that water is the meeting ground for every walk of life.”

And after only two years of being the Charleston Waterkeeper, Cyrus Buffum finds himself no longer swimming against the tide – it’s now coming in with him.