In basketball, winners rebound. But it’s not for the faint of heart. You have to be a warrior, willing to sacrifice your body and fight for the ball. You have to do whatever it takes to seize the moment and then make the most of your second chance. It’s a lesson Bobby Cremins, the 2011 SoCon Coach of the Year, preaches to his team on the hard court as well as embraces in his own life.

by Mark Berry

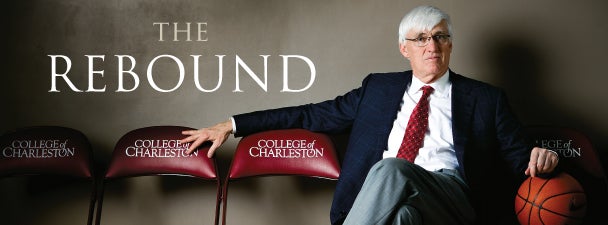

Photos by Terry Manier

Bobby Cremins says he’s not a legend. He’s wrong.

Quick to deflect praise and adulation, no matter how deserved, he’ll point to the fact that he has yet to win a national championship – never mind that one of his teams at Georgia Tech made it to the Final Four or that he put together one of the nation’s longest streaks for reaching March Madness or that he’s one of only a handful of coaches to register 100 wins at three different schools or that he’s a former Naismith Coach of the Year winner.

Rather, he’ll talk about his mentor, Frank McGuire, who coached him at the University of South Carolina and had previously won a national championship at the University of North Carolina. He’ll then mention Indiana’s Bobby Knight and Duke’s Mike Krzyzewski, undisputable luminaries of the coaching profession. He’ll tell you in all honesty that when he puts his accomplishments next to those coaches, he feels pretty small.

“But I don’t mind not being a legend,” Cremins says. “I’m very happy with who I am. I know what a legend is, and I have coached against a few, like Dean Smith, and those are legends.”

Granted, by Cremins’ narrow definition, he’s not a legend. However, by most other definitions of the word in everyday sports talk, he is. Cremins is perhaps one of the most recognizable figures – and heads of hair, for that matter – in all of college basketball today. His track record for rebuilding programs – first at Appalachian State, then at Georgia Tech (where his name graces the court) and now here at the College – merits considerable attention and celebration. At each stop in his coaching career, he has been one part architect, another part mason, fashioning basketball programs that are hold-your-breath, then scream-your-lungs-out thrill rides. And now in his fifth season at the College, he’s again working his magic of toppling giants and vying consistently for conference titles.

But his win-loss record, while impressive, may just be the least interesting thing about him – as is usually the case when it comes to legends.

Empire State of Mind

To understand Bobby Cremins, you have to know the Bronx. His childhood neighborhood was the proverbial melting pot of ethnicities and nationalities. And it was tough – the kind of tough you would find in a Martin Scorsese film. Gangs were prevalent; violence was not uncommon on the streets or echoing down the hallways of an apartment building. You learned pretty quickly to stand up for yourself because the alternative was none too pleasant.

“That’s just New York,” Cremins shrugs, with a smile.

Yes, the streets of New York could be mean, but they could also provide meaning – and community.

Cremins is quick to point out that life was not all that grim. To the contrary, it was a near paradise for a kid who loved sports. Just outside his apartment building was a large schoolyard where he played softball and basketball. And, of course, there was always a pick-up game of stickball or football being played in the streets.

Sports provided common ground for the neighborhood kids. They played it together. They watched it together. And they talked about it all the time. While his friends religiously followed Mickey Mantle’s exploits with the hometown Yankees or Willie Mays with the New York Giants, Cremins followed the heroics of Hank Aaron, the great Milwaukee Braves slugger.

“I guess I wanted to be different,” he recalls of his selection of a baseball idol.

This may have been one of the first indications that Cremins had interests away from home – that there was a world outside of the 42 square miles that constitute the Bronx.

And sports would prove his ticket out.

Cremins’ parents, who were working-class Irish immigrants, enrolled him at the local Catholic grammar school, St. Athanasius. There, he participated in the first of many memorable basketball tryouts – this one, for the grammar school team. Fortunately, he made the squad.

“Basketball probably saved my life,” Cremins muses. “Without it, I would have gone down a much different road.”

In each subsequent tryout in his life, it wasn’t just a team he was going for, although he may not have realized it at the time. With each dribble, each pass, each shot, it was really a better life he was pursuing when, as a teenager, he spent Saturday mornings going from gym to gym to showcase his point guard play for the Catholic High School Athletic Association. There, he caught the coach’s eye from All Hallows High School, a prestigious private school that the Cremins family could never have afforded without a basketball scholarship. It was a better life he wanted when, after his celebrated playing days at the University of South Carolina, he sought tryouts with NBA teams and the nascent ABA league in an effort to be a professional player.

But perhaps the most telling tryout of Cremins’ life took place on a random New York City playground.

It was the early 1970s and Cremins was frustrated. His professional basketball career wasn’t taking off the way he thought it would. Like so many college graduates whose dreams aren’t immediately realized, he had to move back home and find work. His father, who was a doorman at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, pulled some strings and got him a job as a bellhop. The former USC basketball captain traded in his jersey for the Waldorf-Astoria’s signature bright-red uniform and pillbox hat.

“When you grow up in New York, in my environment, it’s not about having all these things,” Cremins explains, motioning to his desk and the framed accolades hanging on his office walls in the Carolina First Arena. “It’s about having a job, sitting on the bus or train, going to work, then coming back home. There’s not a lot of ego involved – it’s a matter of survival, a matter of working, of staying out of trouble.”

The trouble was, while the pay was decent and the job was good enough, Cremins had a dream. And being a bellhop wasn’t it. Fortunately, after a couple of months, a USC supporter spotted him in the lobby and hooked him up with a real estate job back in Columbia.

But that wasn’t the dream either. And his friends knew it.

Corky Carnevale, Cremins’ teammate and college roommate, was assisting the men’s basketball program at USC when he received a phone call from a coach in Ecuador who wanted to recruit some All-American–caliber players for his team. While Carnevale was unwilling to give up any of the current USC players, he told him, “I’ve got the guy. He’s six-six. Big. Can shoot. Can dunk the ball. He’s perfect for you.”

Satisfied, the Ecuadorian coach set a time to pick up his new star player in New York City, where he was also buying shoes for the team.

After quitting his job in Columbia, Cremins packed his bags for South America and returned to New York. When the coach pulled up in his taxi to meet Cremins, a look of disappointment cut across his face. Shaking his head, the coach muttered, “No alto, no alto.”

Carnevale, of course, had exaggerated Cremins’ height in order to land his good friend this rare professional playing opportunity, but the foreign coach felt betrayed and got back into his cab. But not before Cremins climbed in with him and ordered the driver to take them to the nearest playground.

When they arrived at the outdoor court, Cremins hopped out and paid the kids playing basketball $5 to give him the ball. In short order, he displayed his considerable basketball repertoire and impressed the coach with his skills, if not his audacity and confidence.

They got back into the cab and left later that day for Guayaquil, where Cremins played professionally for the next eight months.

The Mulligan

Cremins was walking along the beach on Hilton Head Island. It was a beautiful June morning in 2006. The sky was a deep blue and the waves crashing couldn’t have been any more relaxing.

His dog Murphy trotted up ahead, and his wife, Carolyn, was only an arm’s length away. Everything should have been perfect. This was the Hallmark-card scene that marketers promise for a life well spent – the peaceful and natural coda to a frenzied and stressful life.

“I found serenity,” Cremins says in a none too convincing voice.

That’s because serenity for Bobby Cremins is not a beach. Yes, when he had finished his 19 years of coaching at Georgia Tech in 2000, he needed a much-deserved break. With student-athletes frequently leaving college early to enter the pros, it was getting harder and harder to keep his teams competitive. Each year the stress of reloading – of reworking his system to accommodate new talent and new personalities – was mounting. The joy of seeing a player develop over four years was becoming a fleeting memory – and worse, his teams were losing. Cremins was burned out. Life on a distant beach sounded pretty good.

Retirement started out the way he had imagined it. There was golf, tennis, walks on the beach. Life was pretty satisfying without the day-to-day headaches of running a basketball program. He traveled around the country giving motivational speeches to different business groups, played in a lot of charity golf events and dabbled in TV as an on-air analyst for college basketball.

Cremins’ original vision was to retire for a year or two, get his energy up and then dive back into coaching. “But I lost my game plan,” he explains. “There wasn’t the financial pressure to get back into it, and I was enjoying myself. During that time, I discovered that maybe I didn’t love coaching as much as I thought I did.”

But by year three, the cracks in this mirage were starting to reveal themselves: Serenity was boring.

Carolyn saw it, felt his emptiness and restlessness. She cajoled him, pushed him to think about coaching again. There were jobs in Tulsa and Oregon State, she told him, but Cremins dismissed them. He wasn’t ready yet – there will be opportunities later, he told himself. Three years became six, and she could see her Bobby turning into an old man right before her eyes – a man whose youthful fire and iconic shock of white hair had inspired not only his players at App State and Georgia Tech, but legions of college basketball fans around the country.

“When I was walking on that beach in June,” Cremins admits, “I was accepting my new life. I had some regrets about not coaching again. I missed waking up each morning with a challenge. But I had stayed away too long, and now the coaching opportunities had dried up. By being non-aggressive, I had missed another year and probably missed the chance to ever coach again.”

Not quite.

Like some guardian angel–matchmaker, Corky Carnevale again came to his friend’s rescue. Carnevale knew that Cremins needed to get back into the game, especially when he heard that the retired coach was starting to play bingo on Wednesday nights. The thought of Cremins excitedly calling out “bingo” in his Bronx accent still makes him laugh today.

Carnevale, who lives in Mt. Pleasant, was following closely the turmoil surrounding the College’s basketball program. In late June 2006, the College had announced the hiring of Winthrop University head coach Greg Marshall, a former assistant to longtime Cougars coach John Kresse. However, the day after Marshall was introduced in Alumni Hall as the new head coach, he decided to stay at Winthrop.

Interestingly, at the time, many sports journalists drew parallels between Marshall’s flip-flop with Cremins’ own infamous reversal when he returned to Georgia Tech after accepting the head coaching job at USC in 1993.

What appeared to be a slammed door on the College was a window of opportunity for Cremins.

Carnevale called his friend about the job and roused him out of his slumber. “Once a coach,” Carnevale says about Cremins, “always a coach.”

“I had something left,” agrees Cremins, who accepted the job in early July. “I missed every aspect of it. I look at the College of Charleston as my mulligan, and I’m trying to make the best of my mulligan. I feel like I regained my purpose – like I got my real life back.”

On the Recruiting Trail

“Dude, is that Bobby Cremins?” a high school teammate asked Andrew Goudelock.

Goudelock, the eventual 2006–07 4A player of the year in Georgia, looked across the court and saw the white-haired coach climb the bleachers and choose a spot away from the crowd. He then noticed that everyone was whispering and glancing back over their shoulders in Cremins’ direction. There was definitely a buzz in the gym now.

Goudelock, who possesses a quiet, almost intimidating confidence, understood that the game tonight – Stone Mountain versus Tucker High School – was taking on new meaning. And he was ready.

Cremins was there specifically to watch Goudelock and his rival Jeremy Simmons play. Goudelock was not being recruited heavily by any major programs, but he had been talking to some of the College’s coaching staff. He knew who Cremins was and some of the players he had coached at Georgia Tech, like NBA all-star Stephon Marbury, but his parents were the ones who were really excited. Remember, Goudelock was only 2 years old when Cremins took his Georgia Tech squad to the Final Four. That night, on the outskirts of Atlanta, both players’ skills shone bright, with Goudelock scoring 39 points, although Simmons’ team would go on to claim the state championship that year.

Cremins soon signed both players – two of four critical pieces in solidifying his first full recruiting class at the College, which also included current starters Donavan Monroe and Antwaine Wiggins.

What those players didn’t know at the time was that Cremins was desperate. Desperate not only to find talent, like any coach, but desperate to plug some very large holes that might sink the program for several years.

By the end of August, just two months after he accepted the job at the College, Cremins knew two things: 1) that his first year was going to be OK because he had an incredible scoring star in senior Dontaye Draper, and 2) that his next year was going to be rough – a kind of rough unfamiliar in Charleston for more than several decades.

Cremins had inherited a program without a freshman class. At near-lightning speed, he recruited and signed Tony White Jr., who joined the team that fall and would go on to play a significant role in the program over the next four years. But he needed more players – and soon. So he had his coaching staff do a full-court press on recruiting that fall and winter.

“I told them to hit the road – go, go, go,” Cremins remembers. “And they went out and found some great talent. I knew if we didn’t have a good recruiting class that year, I wouldn’t be here now.”

Fortunately for Cremins, recruiting is perhaps one of his greatest strengths as a college coach, although he was slightly nervous about this new generation of student-athletes. “My biggest concern coming back was that the kids had changed,” Cremins says. “The world had changed, so I knew they might be different.”

He needn’t worry. During his days at Georgia Tech, he landed some of the biggest names in college basketball, future NBA players such as Mark Price, John Salley, Kenny Anderson, Dennis Scott, Travis Best and Matt Harpring, to name but a few. And you don’t just do that because of your school, no matter how prestigious and high profile the program. It takes considerable charm and charisma to sit in a recruit’s living room or at his kitchen table and connect with his family and sell them all on your program. Pretty quickly, coaches have to develop a relationship of trust with a wide group of people, and Cremins excels not just in the sale (because he doesn’t look at it that way), but in communicating honesty and character.

“Coach Cremins is amazing at in-homes,” says Mark Byington, the associate head coach. “However, there have been times when he has been too honest. Sometimes I’m in the back of the room rolling my eyes, because he’s telling a kid that he’s not our top recruit, and I’ve been working on that relationship for two years.

“But,” Byington adds, “he looks him in the eye and tells him not what he wants to hear necessarily, but he tells him how we will develop the person, not just the basketball player. And a recruit believes him because he’s speaking honestly … from the heart. And in our business, that’s not always the case. By the time Coach Cremins leaves your home, you’re going to want to play for him.”

Ask any of his players, and they will all say they are at the College because of Coach Cremins. Period. Maybe it was because he paid a visit to a recruit’s mother at her work so that she could measure the kind of man he is or perhaps it was because he never has a negative word to say about anyone else – even though other coaches might disparage him or his program during their own in-home visits.

“He truly lives the message that he tells players once they are here,” Byington says. “If we do what we are supposed to do, then it doesn’t matter what anyone else does. Good things will happen.”

And they have – particularly this season. With an upset victory over Tennessee and heart-breaking last-minute losses to Maryland and UNC, Cremins’ current squad has brought a renewed excitement to the program. During games, the energy in the Carolina First Arena is palpable, from the longtime season-ticket holders who are again standing and shouting, to the frenzied student section, where an oversized Cremins’ head spins on a stick, large foam bricks are hoisted during the opponent’s free-throw attempts and undergraduates bear chests painted, “C-O-U-G-A-R-S.”

More important, these Cougars captured the regular season Southern Conference title, guaranteeing at least a spot in the NIT Tournament (their first since 2003). And they have built considerable momentum going into the SoCon Tournament, which they last won in 1999 and would give them an automatic bid to the NCAA Tournament.

“We’re doing well this season,” Cremins observes in his usual understated manner. “We can do something special here. We have a chance.”

Freedom to Create

The team has just finished warming up, and Cremins with them. At 64, he still stretches with the team before practice, jogging up and down the court, doing side-to-sides and high-knee steps. The only indication of his age is a slight hitch in his step this season – a little sciatic pain aggravated from the long bus trips. He then finds a chair along the court and jots down some notes.

The sounds of basketball echo in the empty gym: sneakers squeaking, balls thudding rhythmically on the hard wood, balls clanging off the iron rim and, the best sound of all, the ball shushing through the net. This is serenity for Bobby Cremins.

Cremins stands, stretches his back and walks to center court, calling out, “Everybody, right here.”

The team gathers around its coach. “Where are my seniors?” asks Cremins, looking for Goudelock, Monroe and Simmons. “Those guys are going to get luggage tonight. Are we doing practice in the locker room?”

Those senior players hurry out from the tunnel and quietly join the team, and Cremins begins their preparation for their next game: “Remember, this is no bigger than any other game. Whoever is next is the biggest game of the year. Let’s take it one game at a time. 1 – 2 – 3, Charleston!”

Throughout the practice, Cremins is clapping his hands and telling them, “gotta make good decisions” or “don’t be cheatin’ there” or “be under control” or “come on, baby – get that running game going” or “do that in the game,” after watching one of his freshman players make a goal-jarring dunk.

Cremins’ approach to the game today is much like it was when he was a player – up-tempo, loose and exciting. His favorite athlete growing up and the player he styled himself after was Bob Cousy, the Boston Celtics great known for his behind-the-back passes and offensive flair. In Cremins’ program, his players are given a lot of freedom to create their own scoring opportunities.

Monroe describes Cremins’ coaching style as “raw,” because “he lets us play, you know, do what we do, and when we don’t, that’s when he gets onto us.”

It’s obvious the team loves playing for him. He’s an eye of calm in a storm of chaos that can be basketball, on and off the court. Although Cremins doesn’t shy away from confrontation when the moment or individual warrants it, his critiques are not in-your-face yelling matches and needless browbeating.

Instead, Cremins almost always focuses on the positive. He treats his players like students of the game, just as he is, even after nearly six decades of playing and coaching the sport. Lining the top of the team’s locker room are inspirational messages, such as “Choose Confidence,” “Respect Everyone Fear No One,” “Stay in the Now” and “Attitude More Important Than Talent.” Cremins conveys and reinforces these ideas in person each and every day. He sees basketball as very much a mental game, and it’s through nurturing the players’ confidence that he knows they will do great things.

As Associate Head Coach Byington puts it, “Cremins believes in them before they believe in themselves. And because of that, they achieve things they never thought they could do.”

His student-athletes, both past and present, call him a player’s coach, meaning he cares for them as people and isn’t some distant dictatorial figure in their lives spouting Lombardi platitudes about how winning is the only thing. They go to him for advice on family, school or whatever is affecting them as they adjust to college life. They may even see Cremins, his green tea in hand, waiting for them at their 8 a.m. class, just checking in on them – because academics comes first in his program. It’s no wonder that Cremins receives phone calls not just from his three children, but from many former players on Father’s Day.

“When I first came here,” says Goudelock, the 2011 SoCon Player of the Year who now holds the College’s all-time scoring title, “we butted heads over everything – grades, my decision making. Every night, I would go to his office and we would argue. We were both competitive, both had fire, but we finally found common ground. The stuff was my fault, and I was making stupid decisions. The biggest thing he taught me was that I was just blaming everybody else, and that I needed to look at myself. That’s when it changed for me.”

As sophomore Willis Hall explains, “Coach is always telling us to find solutions … look to do something better. And he means that both in basketball and in our lives.

“That being said,” Hall adds with a laugh, “I don’t think I will ever be right if we had a disagreement – even if I proved it was his gun and his bullet, I still don’t think I would be right.”

Everyday Champion

For better or for worse, athletics play a prominent role in the life of a university. They help raise the profile of a school and may shape the perception held by both fans and those who never even pick up the sports section of the newspaper. When done right, sports can add spirit and pride to the campus and college family, which then spill over into the local community and beyond.

That’s why it’s critical to have head coaches who are quality ambassadors of the school, says Athletics Director Joe Hull: “I like to think that the men’s basketball program and Coach Cremins help the College with our national reputation. Frankly, he may be the best guy who has coached in college in the last 30 years. So many people are friends with him … trust him. And that’s a great thing for our school.”

“Bobby is one of the most down-to-earth people that I have ever met,” agrees John Kresse, who coached the Cougars to national prominence in the 1980s and 1990s. “It’s never about him, his ego, his great résumé. He’s always about the other person, always willing to help the student-athlete, other coaches, the fans. He’s one of the best champions for the College of Charleston.”

And there it is: this idea of champion – a real kind of champion. An everyday champion.

Yes, Bobby Cremins is a “flat-out winner that possesses magical communicative skills,” as college basketball analyst Dick Vitale says. Both Maryland’s Gary Williams and Duke’s Coach K cite him as a “great competitor.” And UNC’s Roy Williams, whose defending national championship team suffered an upset at the College last year, notes how graceful he is in victory and that when people say Cremins’ name, “they always smile.” High praise, indeed, from those in the know of college basketball.

But Cremins transcends his sport. Just ask the local chapter of the American Cancer Society about his involvement in Coaches vs. Cancer. Or ask the thousands of supporters who feel connected to the program because of his approachability and his genuine willingness to help out in any way possible, whether through a speaking engagement, personal note or just a one-on-one conversation. If time is money, then Cremins’ giving could be measured in the billions.

Or, most important, ask the hundreds of players who entered his basketball program immature boys and left determined, responsible men ready to take on the world.

Taken together, that’s what makes a coach truly legendary. And those are the legends that we desperately need in sports today.

Lucky for us, we have one.