We asked one of our new faculty members in political science to tell us why he left the world of aid work to enter the hallowed halls of academia. His answer – and honesty – will surprise you.

by Christopher Day ’95

The truth is that I burned out. In May 2004, I was a project coordinator for Médécins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) in northern Uganda. In the latter stages of what was then described as the “biggest neglected humanitarian emergency in the world,” the two-decade war between Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army and the Ugandan government had displaced 80 percent of the north’s civilian population. Our team was running a massive health and nutrition program for tens of thousands of these internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Lira District.

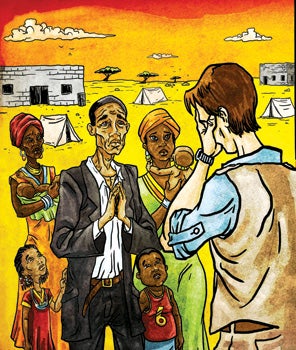

One particular day I was conducting an assessment in an ad hoc IDP camp a couple of hours north of Lira town. The Lord’s Resistance Army had been attacking villages around the area. Unsurprisingly, the only structures that stood in the dusty trade center – a few dilapitated school buildings – were overflowing with malnourished children and their traumatized parents. As the first and only non-governmental organization (NGO) on the scene, we were overwhelmed both logistically and emotionally.

Much of my experiences had been like this one. South Sudan. North Sudan. Ethiopia. Nigeria. Sierra Leone. Côte d’Ivoire. Even Kashmir. I thought I had developed thick skin. But that day, standing amidst a sea of despair, the school’s headmaster, a man my age in a dirty and oversized suit, approached me and asked me for help. He wasn’t talking to me as a black victim to a white aid worker. But as a fellow human being.

And there I was, unable to respond – we were, after all, there for malnourished children and not adults. It wasn’t just bearing witness to his personal misery. Or even the wretchedness of the rest of the camp. It was the biting realization that the bigger structural problems underlying this war – poverty, violence, repression – were not going to be solved by a small group of aid workers in a frantic afternoon of baby weighing. If one had listened closely, one could have actually heard the sound of my spirit being snuffed out like a match. I didn’t want to do this stuff anymore. But I had pigeonholed myself into such a narrow skill set – running relief programs in rebel-held areas of sub-Saharan Africa – that this crazy job was the only thing I knew how to do with any level of competency.

So here’s the good news: Somehow (after detours through Sri Lanka and Darfur), I managed to fall into an academic career that allows me to study bigger structural problems. Furthermore, I’m rather cosmically (even comically perhaps?) at the College, my alma mater. Here I had a two-year stint as an adjunct instructor in between Doctors Without Borders gigs. Charleston is where I met my wife, and where our son was born. My dad even lives here. It was in no small part due to the encouragement from the College’s terrific political science faculty that I pursued a Ph.D. in political science. And it was in no small part due to the terrific advisers at Northwestern that I made it through six amazing years of graduate school (note: I miss Chicago, but not being a graduate student).

Upon reflection, making the transition from aid work to academia was fairly straightforward for a number of reasons. The first and obvious one is that my field experience drives my research interests: I study armed groups in Africa (huge surprise). Having navigated the politics of civil war in order to deliver relief to populations in crisis provides unique insight and a solid empirical foundation for my scholarship. In other words, I’ve been up close and personal with a range of rebels and soldiers alike, and you cannot learn this from a book. My past life also provided ready-made research networks within the countries I used to work. I take great pleasure in rolling up in Juba, South Sudan, and staying with the Doctors Without Borders team, celebrating holidays with my friend the Ugandan general and his family, or catching up with ex-RUF in Freetown, Sierra Leone (they may be war criminals, but they’re still my friends).

Second, working in a team of aid workers is not unlike working in an academic department. Granted, the stresses faced in the field (life and death) differ markedly from those in academia (publish or perish). But in the aid world, I worked with a variety of missionaries, mercenaries and mostly misfits from around the world. Some people were cool. Others were crazy. So this was a good training ground for navigating the thicket of dysfunctional egos and rampant insecurities that populate much of academia, and most of political science. Fortunately, the poli-sci department at CofC is populated primarily with funny, smart, excellent human beings, with a few notable exceptions (I’m looking at you, Professor Jordan Ragusa). Plus, in the NGO world, hierarchy and administration are both fairly nebulous concepts. So I feel right at home at a college.

Finally, both the aid world and academia engage the world in ways that matter. Humanitarian aid seeks to save lives and alleviate suffering for victims of manmade disasters. The Department of Political Science at the College is committed to the rigorous study of politics, power and place, expanding opportunities for learning and service, career preparation and civic participation locally and globally. The second form of engagement may seem trivial when compared to the first. After all, political science by necessity maintains a distinct objectivity and the ability to dispassionately analyze and explain how politics work. But many in the discipline are motivated to solve empirical puzzles in order make the world a better place.

And at the College, teaching political science can be a form of advocacy that educates students about populations in crisis that are on the edge of survival in the midst of the world’s forgotten conflicts. On the flip side, the aid world would do well to think things through politically instead of going on a self- absolving rampage devoid of critical thinking (I’m looking at you, Invisible Children).

In sum, doing my impersonation of an aid worker for a decade was suitable preparation for doing an impersonation of a political scientist. None of this is to say that I don’t miss the good old days of humanitarian aid – the work, the lifestyle, the adventure. I remain very proud of my time with Médécins Sans Frontières (Nobel Peace Prize and all) and stay closely engaged with contemporary humanitarian issues. But after burning out years ago, it’s good to be home in Charleston.

– Christopher Day ’95 is an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science.

Illustration by Baird Hoffmire