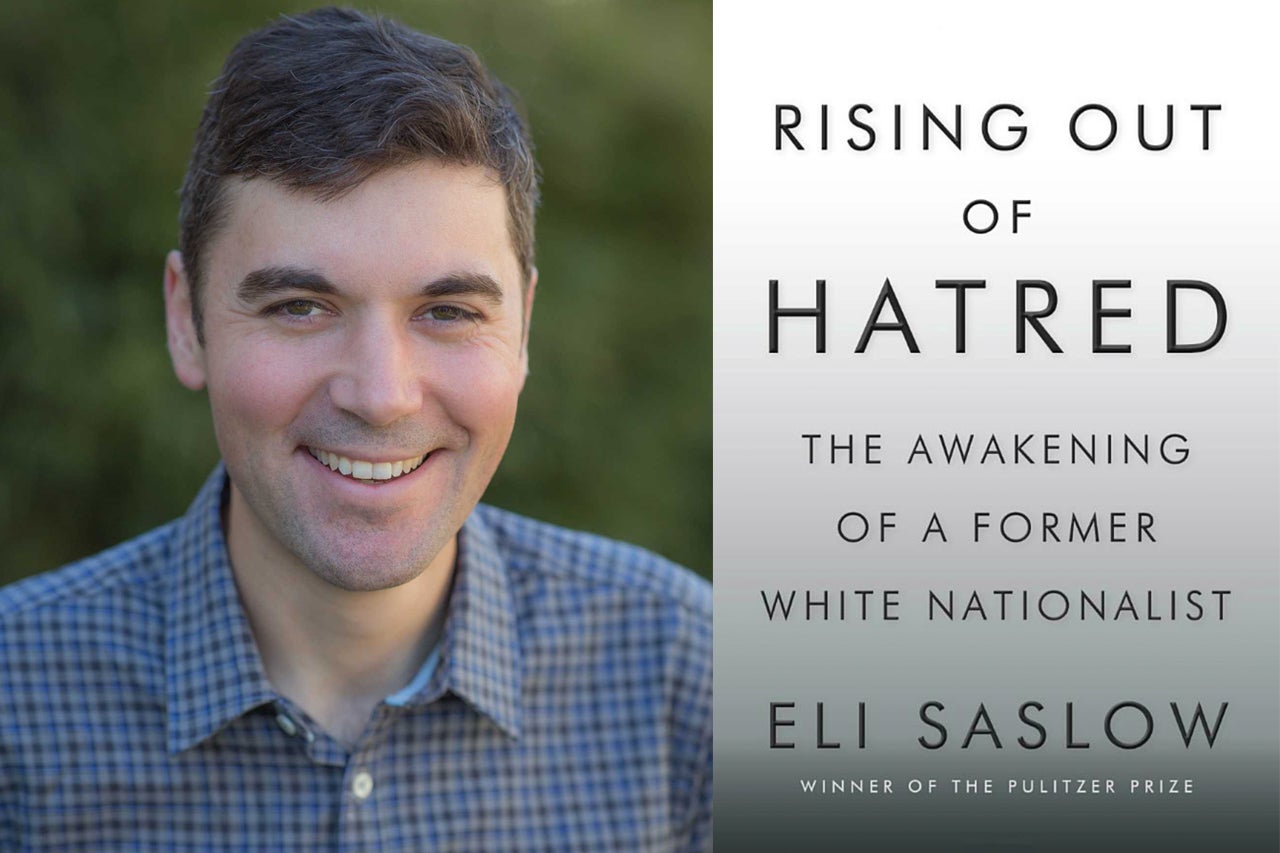

As part of “The College Reads!” program, the College of Charleston will present an evening with Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Eli Saslow, the author of Rising Out of Hatred, on Tuesday, Oct. 29, 2019. Saslow will speak at the Rita Liddy Hollings Science Center room 101 at 7 p.m. He’ll talk about his book, which chronicles the true story of a prominent white nationalist who eventually disavows that ideology as well as the larger national conversation regarding white nationalism.

The event is free and open to the public.

Saslow – a full-time contributor to The Washington Post – covers the human stories behind the most divisive issues of our time. From racism and poverty to addiction and mass shootings, his work uncovers the impact of major issues on individuals and families. Saslow first became aware of Derek Black, the aforementioned white nationalist that became the focus of his book, while spending time in Charleston covering the aftermath of the massacre at Emanuel AME Church in 2015.

The College Today sat down with the author-journalist to understand how he discovered and chose to address this important and charged topic.

How did you initially become aware of Derek Black and what drew you to this particular narrative?

The first time that I went on Stormfront.org, the white nationalist website that’s run by Derek Black’s father Don, I was researching the response in that community to [the suspect in the Emanuel AME Church shooting] Dylan Roof’s actions. I was actually here in Charleston. Derek had just announced that he was leaving the white nationalist movement, and that prompted a huge discussion thread on the site’s message boards. That drew my attention because I wasn’t aware of Derek before that or of the status he held in that movement.

Because I write about big issues going on in the country, I’ve unfortunately been writing about mass shootings in recent years. Many of those are linked either directly or indirectly with white nationalism, so this movement has very much been on my radar.

Derek’s story is unique. He was raised as a white nationalist and was essentially regarded as the heir apparent to this movement in the U.S. He was mentored by famed white nationalist and former head of the Klu Klux Klan David Duke, who is his godfather. Yet he chose to leave all of that, which I find compelling. He renounced white nationalism and vowed ultimately to fight back against it. So, that piqued my curiosity. I wanted to investigate what changed for him.

White nationalism would seem to be the kind of issue that either turns you off or really stokes your interest. How is it that you managed to maintain objectivity and not let your personal perspective steer the narrative in this book?

Of course white nationalism is something I regard as awful and very damaging, but I think sometimes the most powerful writing and reporting is found in the facts. This ideology has caused incredible damage, yet someone such as Don Black, who has spent his life doing irredeemable work, should still be reported on fairly. That’s my job as a journalist. I knew from the beginning that if I reported this story right – if I executed it properly – the facts of the story would point to the light, so to speak.

Your research for this book appears to have been exhaustive. Were you surprised at the access you had to Derek Black, his father and Derek’s friends?

I was a little surprised, particularly with Don. But I knew that having good access to Don would be essential for this story. Don and Derek’s relationship was so close, and despite his horrific ideology and acting as a terrorist icon for much of his life, Don really loved his kid. And Derek’s loyalty to his father and his love for him was what kept him in white nationalism for so long. Given that, I knew it would be important for readers to understand the course of their relationship. And once Derek committed to spending time with me for the book, I knew that Don would probably want to share his side of the story almost as a counter to what his son was relating.

These days, the two of them don’t talk to each other, so I privately suspect that sitting down with me for interviews to talk about those years was a chance for Don to reconnect with his kid.

Reading the book, it’s clear that Derek initially struggles to share his conversion story, yet evolves to become outspoken about it. How did that play out in your interviews?

Trust in these kinds of relationships between source and reporter is something that takes a long time to build. The first time I interviewed Derek, he asked me to meet him in a random city so that I wouldn’t know where he lived, and he was still living under a fake name. Also, at the outset, he was protective of the people who were close to his story.

In my job, I’m fortunate that I have the luxury of not needing to work quickly. So, I stay with a subject as long as possible to ensure that I get the story right. With Derek, it wasn’t just that I got to spend tons of time with him, but it was also that he made available all of the text messages and emails that he was sending back and forth in college with all these people. That was the nature of the trust we built. And ultimately, he and the other people who appear in the book decided that the risks of exposing this very personal narrative were worth it.

It appears that both David Duke and Richard Spencer (a contemporary white nationalist) were very forthcoming as sources. Is that the case?

Unfortunately for the world, David Duke is happy to speak whenever anyone asks him to. What was challenging with him was getting him to talk not about white nationalist ideology, but about Derek and their relationship. The two of them were very close; Derek spent several Christmas vacations alone with David Duke in Europe. But since 2015 when Derek essentially renounced white nationalism, the two haven’t spoken.

And Richard Spencer, he was initially cautious, but also interested in getting his perspective out there. Again, I’m always reporting in person, so I’m there face-to-face with the individual that I’m writing about and I’m always willing to spend a lot of time with them. So, trust tends to build over time and you become less intimidating as a writer and more of an actual person to your sources.

What do you hope readers will take away from your book?

Well, two things. One, I hope that it will be something of a reality check in terms of how dangerous and how present the white nationalist ideology is. Not only in the current moment in the U.S., but also in American history – in what this country has been in the past. But in addition to sort of sounding the alarm, I also hope that this story suggests that there’s something that we can all do about this situation. We can confront it in our own ways much as the people that I interviewed for this book have done.