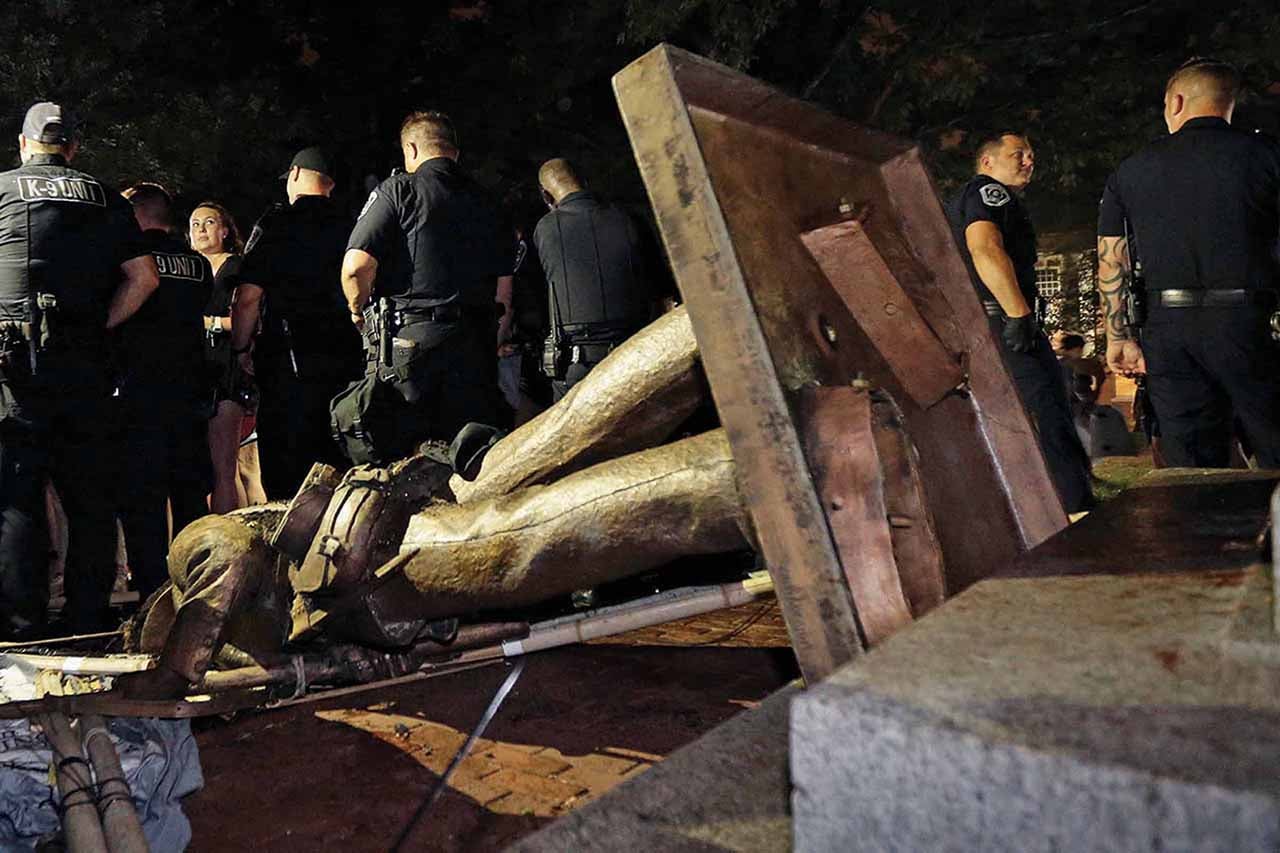

On a late summer evening in 2018, a large crowd of students gathered around a Confederate monument at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Chanting and bearing signs, the protesters toppled the eight-foot statue known as Silent Sam – which had stood atop that granite plinth for more than 100 years – pulling him to the ground with cheers. It was a watershed moment, and one that was indirectly influenced by the research of someone now teaching history at the College of Charleston.

Professor Adam Domby specializes in the Civil War and Reconstruction, the 12-year, post-war period that empowered formerly enslaved people. Specifically, his research focuses on the role of lies and exaggeration in the creation of “Lost Cause” narratives regarding the war. He examines the connections these narratives have to white supremacy and the pivotal role Confederate monuments play in it, which he writes about in a new book called The False Cause: Fraud, Fabrication, and White Supremacy in Confederate Memory (available in the College bookstore and on Amazon).

History professor Adam Domby (photo by Kate Thorton)

Domby was a graduate student at UNC in 2009 when he discovered a document that previous historians had largely overlooked. It was a 1913 speech given at the dedication of Silent Sam by Julian Carr, a rich industrialist and white supremacist who was one of the most prominent Confederate veterans of that era. The discovery of the speech only served to strengthen the resolve of the Silent Sam protesters.

“In his speech, Carr said explicitly that this is a monument tied to white supremacy,” says Domby. “He’s very upfront about that. And, in fact, Carr said that it’s really a monument to the overturning of Reconstruction.”

The speech served to promulgate what Domby refers to as “key falsehoods” underlying the Lost Cause narrative, which positions the cause of the Confederacy as just and heroic. Domby’s work focuses on the role of lies and exaggeration in the creation of Lost Cause narratives regarding the war, scrutinizing the connections these narratives have to white supremacy.

“Among those key lies,” he says, “is the assertion that the war had nothing to do with slavery, but was solely about states’ rights, which is patently false. Another is the claim that slavery was a benevolent institution, that it benefited enslaved people. That, of course, is patently false as well. Slavery in the South was premised on terror and violence. Period. It was the extraction of labor through torture and terror.

“These monuments,” adds Domby, “are ultimately about the time in which they were crafted and not about the time they commemorate. They are not about the Civil War; they’re about the Jim Crow era. What’s remarkable is that narrative, which allowed and justified white supremacist politics in the early 20th century, is still being used today for the same purpose.”

Featured image by Associated Press/Gerry Broome