History professor Jacob Steere-Williams has taken a particular interest in the COVID-19 pandemic. Like so many others, his home and work life have been disrupted by this disease. But, as a scholar who specializes in the history of infectious disease and public health, his interest is more focused on how this current plague intersects with the past.

Steere-Williams recently completed a book – The Filth Disease: Typhoid Fever and Epidemiology in Victorian Britain – that will be in print this fall. His tome examines how modern epidemiology emerged as a function of government in response to one of the most feared epidemic diseases of the 19th century – typhoid fever. In addition, he regularly teaches courses such as Epidemics and Revolutions; Disease, Medicine and History; and Science, Medicine and Empire in the Modern World.

The College Today sat down with Steere-Williams (virtually) to better understand how historical thinking about previous pandemics can help us process and understand COVID-19 today.

COVID-19 caught many of us by surprise because it’s well beyond the scope of our experience. What occurrences in history compare to this, if any?

Although it’s a “novel” coronavirus exploding across the world today, the human experience of, and response to, pandemic disease is anything but new. In some deeply fundamental ways, the human condition is inexorably tied to disease. As a historian it’s what makes this subject resonate so much with the world around us, particularly in the midst of a pandemic crisis. We know that each outbreak of disease is contingent to time and place, but examining specific historical examples – as well as broader patterns in human behavior in response to disease – can help us see how that disease impacts human history.

Even if we only consider the past several hundred years, there are numerous examples that help to contextualize our current crisis. In important ways, the history of settlement in the Americas is a story of both colonization and infectious disease. Smallpox, a European children’s disease at the time, ravaged the indigenous populations of the Americas. This demographic crisis opened the door for European settlement and created a labor shortage that fueled the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

By the 18th century, there were repeated and massive outbreaks of yellow fever, a mosquito-borne disease, all along the east coast of the U.S. In the 18th and 19th centuries, in cities like Charleston, Philadelphia and New Orleans, city officials debated what to do to stop yellow fever. Should they quarantine ships, isolate individuals, clean up cities, stop the economy, infringe upon individual rights? These were strained and political questions then as they are now.

In the 19th century, it was a cholera pandemic that swept across the globe in terrifying fashion. This highly-virulent, water-borne disease killed with such rapidity it was said to seize soldiers in perfect health one day and put them in their grave the next. In 1831, cholera had already invaded the Mediterranean and most of Europe, but not America. Most Americans believed they were immune to the disease, that they were stronger than Europeans in health and in governance.

At the time, it was said that cholera had originated in Asia; it was even called “Asiatic Cholera,” typifying a xenophobia that resonates with us today with the COVID-19 pandemic. But by 1832, cholera had exploded across American cities, continuing in epidemic form for most of the 19th century and leaving an indelible mark on both death rates as well as urban planning and the construction of water and sewerage supplies.

In the late 1890s and into the early 20th century, the Third Plague Pandemic – a massive worldwide pandemic of bubonic plague – eroded a newfound faith in public health and what one historian has called “the gospel of germs.” On the American West Coast, in cities like San Francisco, where plague hit hardest, residents responded by blaming Asian Americans and targeting Chinatowns, leading to some of the most hurtful and long-lasting government-sponsored measures in American history.

Most of us are somewhat familiar with the story of typhoid fever, the subject of your book. Does that outbreak offer potential lessons regarding the current pandemic?

Yes, the story of Typhoid Mary definitely resonates with the current crisis. Mary Mallon was an Irish immigrant to New York in the early 20th century. She worked in various upper-class homes as a cook and head of the kitchen. George Soper, a sanitary engineer and early epidemiologist curious about repeated outbreaks of typhoid fever, linked Mary as the common cause. Only recently had German bacteriologist Robert Koch discovered what is now called the “healthy carrier condition,” where an individual can be suffering from a disease and actively spread it to others yet show no noticeable symptoms. Mary was quarantined and sent to North Brother Island for decades, where she died. She was called a menace to health although she was far from the only healthy carrier of typhoid at the time.

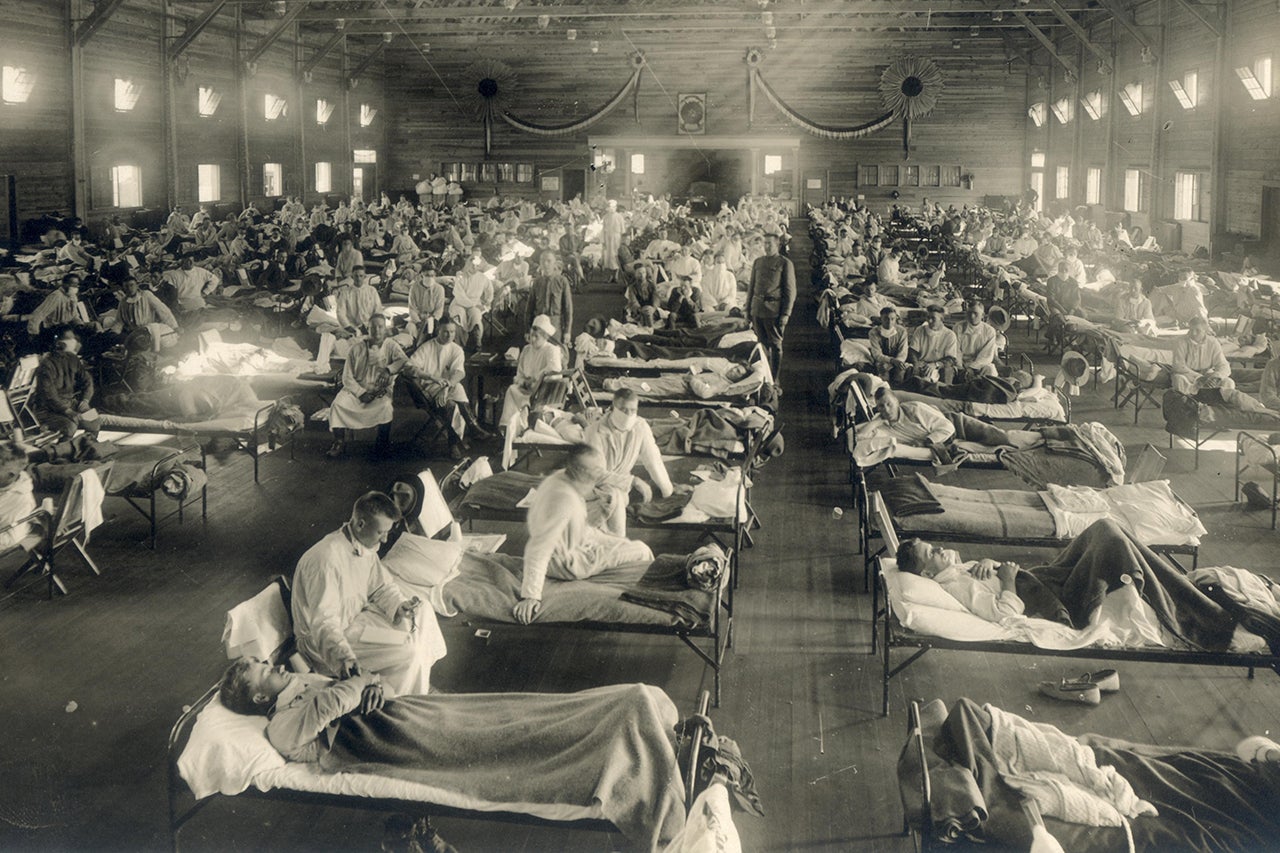

And a lot of people have recently become interested in the lessons we might glean from the last big pandemic disease, the so-called Spanish Influenza of 1918-1919. There are parts of the story that echo with our current COVID-19 crisis: governments called for massive quarantines, businesses, schools, churches and public gatherings were shut down; masks were recommended to stop the spread of a respiratory disease; and scientists mobilized to try to create a vaccine and communicate sound public health measures.

In general, the historical experiences of pandemics tell us that disease is always both biological and cultural. It is indelibly linked to scientists trying to uncover new truths, politicians trying to use an outbreak as a wedge into broader social structures and everyday people trying to manage, cope and fit the crisis into their worldview.

In what ways have you been able to incorporate aspects of COVID-19 into the classes you’re teaching this semester?

When the outbreak presumably began, with cases in Wuhan, China, I started talking to my students about whether they were following the situation and were potentially afraid of a global pandemic. I certainly was hearing the early reports. I gave updates at the beginning of each class and shared news items from around the world with students, giving them time to reflect and discuss. But in January and February it was global news, it wasn’t local news.

That raises another point about the value of using historical analysis right now. It’s been true of past pandemics that unless disease impacts your local community, it’s difficult to take the threat seriously, to heed the advice of experts about preventive and collective public health action. We’re seeing that right now in Charleston, a city that still has few recognized cases.

In my classes right now, which have moved online, I have prioritized both flexibility and taking the opportunity to use historical analysis to help students think through and process this monumental moment in our lives. I’ve shifted my grading to give a lot of credit to student journals, where they are producing their own “primary sources” on the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead of a final exam, I’m asking students to write an essay, using the historical examples we explored in class, that considers what future historians will want to know about the current pandemic. That’s really empowering for students, and their response has been tremendous so far!

How are your students responding to the opportunity of understanding COVID-19 in context with earlier pandemics?

I always end the semester in my classes talking about emerging and reemerging infectious diseases, and reminding students that one day – probably in our lifetimes – we will see a pandemic disease impact the world on a similar magnitude of the historical pandemics we have explored in class. How we individually and collectively respond will matter, and our stories will end up in history classes in the future.

Students typically struggle to see the immediacy of the warning, but they are always keen to see the historical patterns of how we probably will respond. In the past, Americans have blamed pandemics on others, usually on marginalized groups like impoverish individuals, disabled individuals, foreigners, people of color and members of the LGBTQ community. During historical pandemics, we have bickered over individual rights versus the public’s health and over the interests of public health versus the interests of the economy. We’re doing the same thing right now.

Our students are both deeply impacted by this pandemic and are trying to find ways to understand it. I believe the history of disease, medicine and public health can help us all to do that.

Do you feel that, as time goes on, we’ll end up perceiving other lessons from the current pandemic? And if so, what would those be?

What is becoming clear to folks of late is that we, as an American community, and also as a global community, were not prepared for this pandemic. The ironic part of that realization, as a historian, is that no one ever is prepared for a pandemic, for a mutated virus, an emerging infectious disease or a reemerging one. And yet, any undergraduate who has taken my class can tell you what we should have expected and how we probably should have responded.

Pandemics expose human nature, including our xenophobia and greed, as well as our capacity for community, compassion and scientific breakthrough. Over the past several hundred years, what pandemics also show us is the deep-seated ways in which our world is connected globally and how any effective response necessitates a global response. Perhaps one lesson going forward will be the global connectivity in responding not just to infectious disease, but to climate change and a myriad of ecological and environmental issues.

Feature Photo: Soldiers from Fort Riley, Kansas, ill with Spanish flu at a hospital ward at Camp Funston circa 1918.