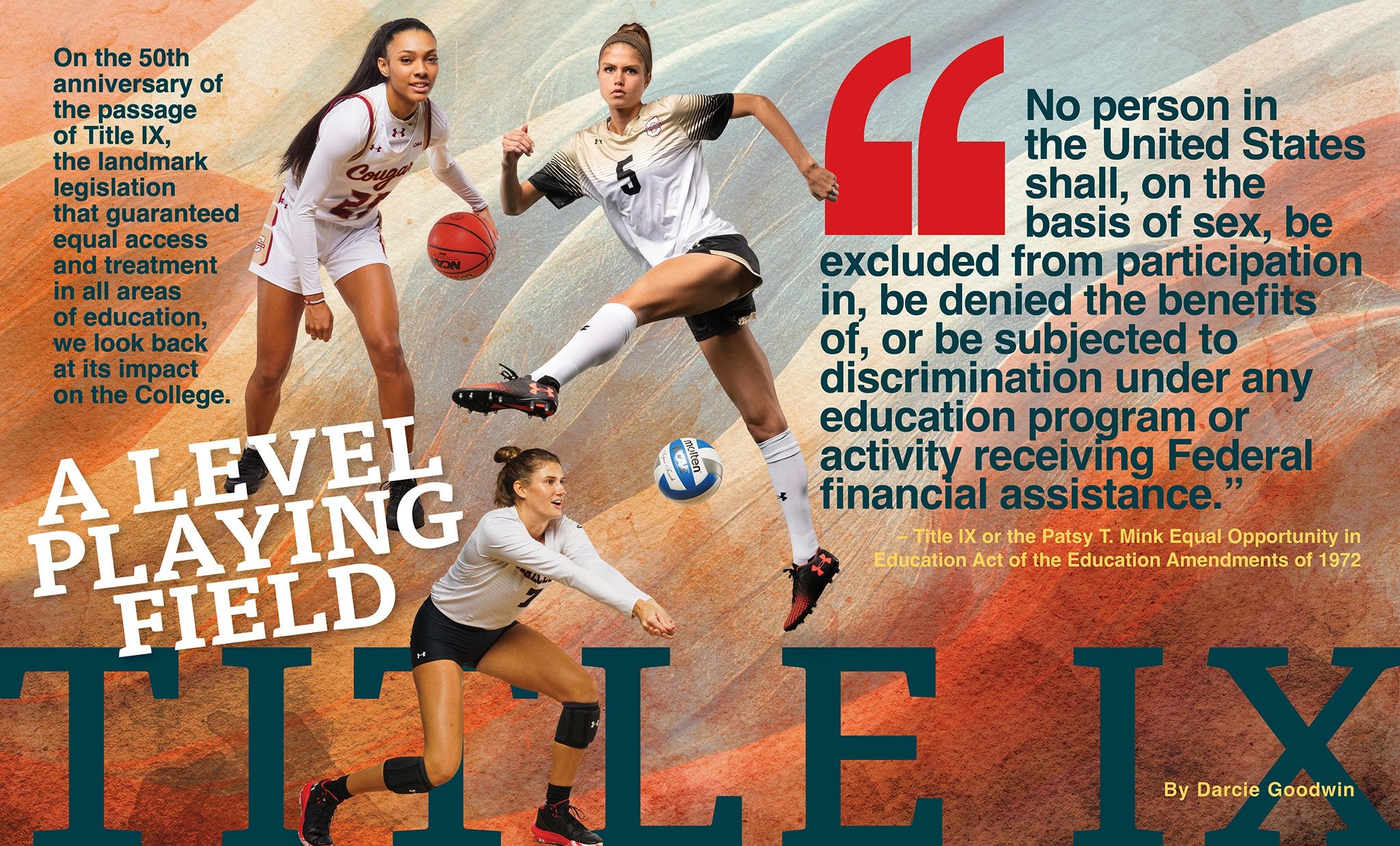

“No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

– Title IX or the Patsy T. Mink Equal Opportunity in

Education Act of the Education Amendments of 1972

One sentence. That’s all it took to begin the process of profoundly breaking barriers for women in higher education. Passage of the 1972 law initially – and somewhat unintentionally – had the greatest impact on athletics. According to a recent Title IX analysis by the Women’s Sports Foundation, 3 million more high school girls have opportunities to participate in varsity sports now than they did before passage of the law. Now, women make up 44% of all college student-athletes, compared with 15% before Congress passed the law.

The College of Charleston was at the forefront of this transformation. Until Title IX, women’s sports at the College consisted solely of clubs, but just eight years after the passage of the law, the Women’s Sports Foundation named CofC the No. 1 female athletics program in the nation. Today, the College has 11 female varsity teams with 213 female student-athletes – 111 of whom are on athletic scholarships. The law’s true impact, however, can be felt by the lessons learned and bonds formed among female student-athletes and coaches who have positively influenced generations of women through sport just like their male counterparts.

“The positive and profound impact of Title IX continues to make us stronger as an athletics department and university,” says Matt Roberts, vice president and director of athletics at the College of Charleston. “Our women’s athletics programs have not only produced championship moments, but, most importantly, helped mold countless women leaders who make a substantial difference in their communities.”

The reach of Title IX, which takes its name from a “ninth title” added to the reauthorization of the Higher Education Act of 1965, has grown over the years to better ensure women are able to attain their degrees unhindered. Accordingly, the College has expanded with the scope of the law: first in the 1980s to include protections around incidents of sexual assault and again in the 2000s to add protections against discrimination based on gender and pregnancy.

“As we mark Title IX’s 50th anniversary, we can see its impact throughout campus,” says Leya Nelson, equal opportunity programs director and Title IX coordinator. “Our goal is to remove barriers to excellence so that our students and staff can be the best they can be.”

Title IX’s influence can be seen across campus from women in STEM to women representing 49.5% of the College’s faculty (up from 15.9% in 1972) and from a dedicated survivor support program to a Title IX officer in the Office of Equal Opportunity Programs. None of this progress, however, would have been possible without Joan Cronan, the College’s female athletics trailblazer.

Great Timing

When her husband landed a job at The Citadel in 1972, Cronan quit her job as basketball coach at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, and the family moved to Charleston. As soon as she got her 2-week- and 17-month-old daughters settled, Cronan made a cold call to then-CofC President Ted Stern. Cronan, who had also coached basketball, volleyball and tennis in Louisiana at Opelousas High School and Northwestern State University, wanted to coach women’s athletics at the College.

“Either I was a good or a poor negotiator,” chuckles Cronan, who walked out of the meeting as the women’s volleyball, basketball and tennis coach, as well as the women’s athletic director. “I remember Ted saying that the College needs to do this because of a law that was just passed.”

Hiring Cronan was CofC’s first venture into women’s college athletics. Previously, the clubs organized and paid for transportation, uniforms and coaches. With Title IX, women’s sports received funding.

Nancy Wilson, who graduated in 1973 from Coker University with a degree in physical education, recalls that when her basketball team played CofC, the Cougars lacked a coach. Wilson reached out to the College about volunteering to coach, only to learn that Cronan had been hired. Wilson bemoaned her lost opportunity until her roommate convinced her to call CofC’s new women’s basketball coach.

“It was truly magical,” says Wilson of her conversation with Cronan. “I called this woman to volunteer as a coach, and she not only hires me; she goes on to become one of the best athletic directors in the country.”

Then again, Cronan says it’s always about the team: “I loved working with Coach Wilson. There would be no Serena without Venus – we made a good team.”

Title IX had an added bonus for these two driven women when then-Provost and Dean of Faculty Jacquelyn Mattfeld, a self-professed “militant” in response to institutionalized sexism, lobbied to increase their salaries.

“Without our pursuing it, Jackie had our salaries seriously increased thanks to Title IX,” says Wilson, who notes that she was part of the first wave of female coaches who didn’t have to teach classes.

Cronan and Wilson went on to coach CofC teams that competed for numerous national titles, including finishing No. 2 three years in a row in tennis and as runner-up three years in a row in basketball. Hiring Cronan put CofC ahead of the game in South Carolina. With their focus on football and the deadline to comply with Title IX athletic requirements not until 1978, the University of South Carolina and Clemson University entered women’s athletics later. The College embraced and supported women’s athletics from the start.

Before women’s athletics were part of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), they were in the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW). AIAW not only took five regional winners to the nationals; it gave the three best at-large teams the option to pay their own way.

“We were very fortunate that the College of Charleston always sent us to play in some of the national championships. Very few schools of similar size would put money into that,” says Wilson. “We were not always first in our state. If CofC hadn’t sent us, we wouldn’t have had some of the wins, like second in the nation.”

Talent Scouts

CofC’s program attracted major athletic talent, including Marie “Scooter” Barnette ’78, who transferred to the College so that she could play basketball in the AIAW, and Luanne Gillis Clarey ’78, the College’s first female full athletic scholarship recipient.

“When colleges started opening up, we were competing with all institutions, no matter the size,” says Barnette, who was also recruited to play volleyball. “We were playing established schools – and we were beating them.”

Barnette credits a lot of her success and respectful attitude to Cronan’s influence as a coach. “Joan was always a visionary, always a notch up. She was a fierce defender of women’s athletics, but always respectful and respected.”

The athletic scholarships were a big help in recruiting top female talent to the College.

“It was really fun to watch CofC women’s athletics blossom,” says Cronan. “Title IX gave women a place on the sports field, which was a male-dominated area. Today, you can’t turn on the TV without seeing women’s sports and female commentators.”

Scholarships certainly made a difference with Clarey. She knew she was going to play collegiate basketball; she just didn’t know where. When Cronan presented her with the opportunity to play varsity basketball on a full scholarship, she took it.

“I was an exceptional basketball player,” says Clarey, who started playing on the girls’ varsity high school basketball team when she was in seventh grade. “I had a killer jump shot that a professional player taught me.”

Even with the passage of Title IX, Clarey could see the inequities of men’s and women’s sports, from the number of basketballs available to modes of transportation.

“Without Joan, we wouldn’t have had what we had,” says Clarey. “Joan let us feel like we had everything. She never, ever complained. She gave the best of the best, so we felt like we were ‘It.’ We were a team.”

That support made a big difference when it came to the uniforms for the College’s women’s basketball team. When Clarey first joined the team, their warmups were pink. “We were known as the pink panthers,” laughs Clarey. “Fortunately, we ended up getting new uniforms and warmups, all in Cougar colors.

“We were fortunate to have women like Joan who would step out of the boundaries,” she adds. “It’s mind-blowing to see where women’s sports are today. I would love to be playing today with the opportunities, money and demand.”

UT Knoxville lured Cronan away to be athletic director in 1983. “I feel fortunate to have worked for two outstanding institutions – the College of Charleston and the University of Tennessee, Knoxville – that said yes to women before it was cool to do so, and both universities have continued in that success,” she says.

A year later, Wilson left to coach basketball at the University of South Carolina, and Barnette took the over as the women’s basketball coach at CofC. As coach, Barnette remembers hearing noises about a media story on coaches’ salaries, and despite the state announcing no salary increases, she got a raise.

“I think Title IX had something to do with it,” says Barnette.

When Wilson returned to the College in 2003 as a physical education instructor and basketball coach, she saw a more level playing field. “We were NCAA Division I and fully funded.”

The Reach of Title IX

While athletics was the most forward-facing aspect of Title IX, the law always had a broader reach. Its scope expanded in the 1980s to include sexual misconduct. Eileen Baran, then an assistant to the vice president of student affairs, spearheaded the College’s program called CARE (Crisis Assistance Response and Education) after learning about sexual assault cases on campus. Today, CARE is the Office of Victim Services.

“CARE was the extension of Title IX enforcement for students and opened the door to assisting with any form of victimization,” says Jeri Cabot, retired dean of students. “The program expanded to include outreach to raise awareness about what constitutes assault. It really put the processes in place for the College, and I’m pleased to say that they work.”

In the 2000s, the power of Title IX further strengthened when a series of “Dear Colleague” letters circulated by the U.S. Department of Education Office of Civil Rights raised awareness about Title IX and resulted in its application expanding to include gender identity and pregnancy discrimination. Kris De Welde, director and professor of women’s and gender studies, notes that politics and student activism have played a role in the law’s strength.

“There have been times when Title IX has been a political hockey puck at the expense of student well-being and safety,” says De Welde. “Still Title IX’s power to remove federal funds can be a powerful motivator to adhere to the law.”

To ensure compliance and to facilitate and protect people from discrimination on the basis of sex, universities across the country, including at the College of Charleston, established Title IX officers. Kimberly Gertner, associate vice president of human resources and employee success, took that compliance a step further and created a clear, centralized civil rights function with strategic campus partners in order to have broad-based involvement.

The success of the College’s Title IX compliance can be seen throughout campus and in its demographics. “CofC started as an institution restricted to white men,” says De Welde. “Now women represent a majority of the students on campus. This would not be possible without Title IX.”

Sam Gjormand is not crazy about the word trailblazer.

“People throw that word around, and it is a hard thing for me to fathom,” she says.

But what else do you call the Cougarsʼ director of baseball operations (DBO) and the first female baseball coach in Division I college baseball history? What word better describes someone who is a role model for young girls?

“I don’t feel like I’m doing anything special,” she says. “But I know the opportunities that have been granted to me are pretty cool. I definitely don’t take them for granted.”

Baseball is in her blood. Her father, Mark, coached high school baseball for 35 seasons. Gjormand was exposed to the game early. Very early. “I was at my first game when I was 3 days old,” she says with a chuckle, “straight from the hospital.”

Gjormand played for a couple of years on her high school softball team but was always more attracted to baseball. By her junior year of high school, she quit softball to help manage her high school baseball team. She quickly developed a knack for the game.

In college at James Madison University, the baseball coach asked if she would be interested in being a student manager for the Dukes baseball team. Gjormand spent the next four years doing everything from running on-field practice drills to helping with day-to-day operations behind the scenes.

During her senior year at JMU, Gjormand’s prowess caught the eye of CofC baseball coach Chad Holbrook, who offered her the DBO job. Soon after her arrival in the summer of 2021, Holbrook asked if she had any interest in becoming an assistant coach who would help recruit players. He didn’t need to ask her twice.

Last summer, Gjormand was traveling around the region to recruit talented high school athletes to play for the College of Charleston. It’s a job she loves.

“This is a special place, and I think it has a lot to do with with our players and coaching staff,” she says. “I cannot say enough good things about the people in this program.”

– Mike Robertson