If you had told professor R. Grant Gilmore III two months ago that he would soon be spending a good deal of his time 3D printing masks for healthcare workers, he’d likely have been speechless. As the director of the College of Charleston’s Historic Preservation and Community Planning Program and the Community Planning, Policy and Design Program in the graduate school, Gilmore’s expertise isn’t in the development of medical equipment – it’s in historic preservation, architecture and community planning. But, as it turns out, a 3D printer is just as good at making masks as it is models of historic buildings.

Along with teaching his classes virtually – and administering the two programs he runs – Gilmore has been coordinating local efforts to print masks for use at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In the process of assuming this volunteer role, he’s encouraged others at the College and around the community to do the same.

“I don’t recall where I saw it,” he says, “but I learned that a hospital in Michigan was working with local designers to 3D print masks for healthcare workers. Right away, I decided to use a printer from the historic preservation program to do that. I found an FDA-approved design online and then mentioned this on NextDoor (an online neighborhood gathering space) in case others were interested in doing it as well. That got me connected with the two people at MUSC who are managing this effort, and they supplied a different design that we’re all using now.”

According to Gilmore, geology professor Cassandra Runyon is buying a 3D printer so she can print masks. He says that several other faculty from the College are printing them as well. Information management professor Chris Starr, teacher education professor Ian O’Byrne and adjunct faculty member Jolanda van Arnhem from Addlestone Library have all joined the effort. Gilmore says Sebastian van Delden, the interim dean of the School of Sciences and Mathematics, is also marshaling resources from his school to put as many 3D printers to work as possible to help in this effort.

Starr says that he’s working to upgrade the 3D printers in the School of Business so that they’ll be able to print faster with alternative resins. He hopes to change from the harder, more brittle plastics of most 3D printers to a flexible rubber that can better conform to the face for a tighter seal.

To maximize this initiative, Gilmore is attempting to enlist 3D printer owners across the Charleston area. To do that, he’s been scouring his personal and professional networks to engage more people.

“The design community in Charleston is involved,” he says, “including the local chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIA). Several local architecture firms are printing them now. We’re all trying to print as many masks as we can as soon as we can because we know that our community hasn’t seen anywhere near the number of infections that we’ll ultimately see.”

Part of Gilmore’s role involves liaising with his contacts at MUSC to keep them apprised of the progress he and his fellow volunteers are making. He’s also running interference for them, so they don’t get interrupted with questions. He says that if anyone is interested in joining this effort or has questions, they can contact him ([email protected]; 843.830.6813).

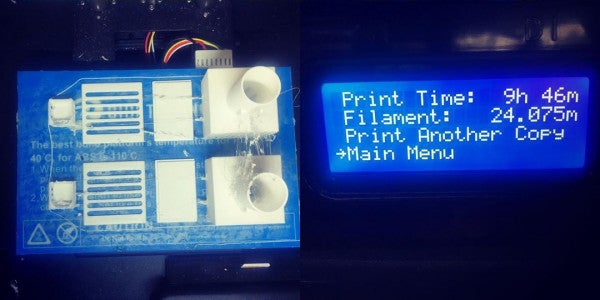

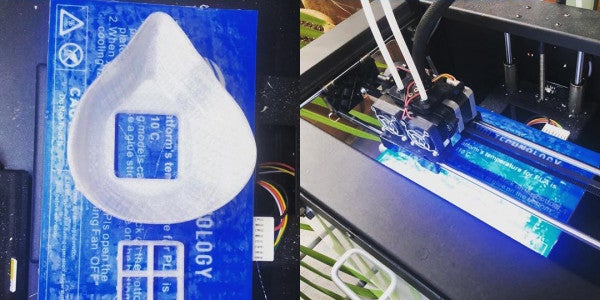

Historic preservation professor Grant Gilmore assembles 3D printed medical masks at his home in Mt. Pleasant, S.C. (Photo provided)

“I’m guessing that the Charleston area has perhaps 100 people with access to 3D printers,” Gilmore says, “so we can really ramp up our efforts with more people doing this, and we should.”

The masks that Gilmore and others are printing aren’t being created in sterile environments, he allows, but says that they will be sterilized after they’re delivered to MUSC. Though the filters are disposable, he adds that the masks can be washed and reused up to 20 times.

So how did a historic preservation professor become so adept at responding in a crisis?

“My wife and I spent seven and a half years living on a small Caribbean island,” Gilmore explains. “We had to learn to be adaptable and resilient. That’s an area that’s regularly hit by hurricanes, so you’re occasionally cut off from supplies and people. We learned to be creative with resources and reuse things, and that’s something that I try to bring into the classroom now. It very much applies to what I teach and is part of why I’m involved in making masks now.”